Considering History: Charlottesville and the Destructive Effects of White Supremacy

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This week, just before the two-year anniversary of the August 2017 white supremacist and neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, my sons and I will once again drive down for our annual pilgrimage to my hometown. Last August, I used the dual occasions of that anniversary and that trip to write about Charlottesville’s largely hidden histories of Confederate memory and segregation, and how much the 2017 rally echoed those white supremacist legacies. Those lessons are more vital than ever in the summer of 2019.

Yet there are other hidden historical legacies in Charlottesville as well. One of the most pernicious is the longstanding erasure of African-American lives and communities, identities and histories, from both the city’s collective memories and its unfolding story. That erasure comprises one of white supremacy’s most deep and destructive effects, and is painfully relevant today.

One of those long-erased communities were the enslaved African Americans who built and sustained the University of Virginia. Rented enslaved laborers formed a core community during the university’s 1817-1825 construction, with the university paying more than $1,000 in hiring fees (more than $21,000 in contemporary value) to slave owners at the 1820-1821 height of activity. The 800,000-900,000 bricks used to construct the Rotunda, the university’s most famous structure, were manufactured by a group of 15 slaves in 1825. Once the university opened in 1825, enslaved men and women worked in numerous roles to keep it running, with an average of more than 100 enslaved laborers performing housekeeping, culinary, and personal service duties (such as blacking students’ shoes) throughout the pre-Civil War decades.

These enslaved men and women were also the frequent target of abuse and violence from the university’s elite male students. In November 1837, a group of drunken students beat the university bell-ringer, Lewis Commodore; just a few months later, in February 1838, two students savagely beat Fielding, a slave owned by mathematics professor Charles Bonnycastle, and the professor had to intervene “for the purpose of preventing his servant from being murdered.” In April 1850, three students abducted and raped a 17-year-old enslaved girl from Charlottesville; six years later, in 1856, student Noble Noland beat a 10- or 11-year-old enslaved girl unconscious because, he told the Faculty Committee, she had been “insolent to him” and such a beating was “not only tolerated by society, but with proper qualifications may be defended on the ground of the necessity of maintaining due subordination in this class of persons.” Noland, like many of these attackers, went unpunished.

For nearly two centuries, neither the University of Virginia nor the city of Charlottesville acknowledged this history of slavery and racism in any consistent public fashion. Much as Thomas Jefferson’s individual status as a slave owner was largely elided, (enslaved African Americans were frequently referred to as “servants” on tours of Monticello until the early 21st century), so too did narratives of Jefferson’s “academical village” highlight the space’s ideals and minimize (at best) the historical oppression on which it was literally built. Efforts are finally underway to redress those absences, including both the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University and a memorial to a cemetery for enslaved laborers. That cemetery had gone unmarked for more than 150 years, a telling reminder of both how fully this community had been buried and how much work remains to be done.

The destruction and burial of African American communities in Charlottesville continued long after the abolition of slavery, and indeed well into the 20th century. Over the course of the century’s early decades, the Vinegar Hill neighborhood, located between the city’s downtown shopping district and the university grounds, became one of Charlottesville’s most prominent African-American communities, featuring 140 homes, 30 black-owned businesses (everything from a jazz club to a fish market), and a church. As with so many African-American neighborhoods throughout the Jim Crow South (and an increasingly segregated nation), Vinegar Hill came to embody both the civic spaces into which African-American communities were forced and the resilience, solidarity, and power with which those communities responded.

Through a series of 1950s and 1960s efforts, however, Charlottesville demolished that neighborhood in the name of “urban renewal.” In January 1954 the City Council adopted a resolution critiquing the city’s large number of “unsanitary and unsafe inhabited dwelling accommodations”; after a very narrowly decided referendum vote, in June of that year the city established a Housing Authority to address this perceived problem. Over the next few years, that agency focused its attention on plans for “redeveloping” the Vinegar Hill neighborhood, which, as one supportive newspaper editorial put it, “is related closely with the rest of the downtown Charlottesville area which seriously needs room for expansion.” Expansion, redevelopment, renewal — these were all euphemisms for the unnecessary, overtly white supremacist displacement of a thriving African-American neighborhood.

In 1960, the Housing Authority proposed a referendum in support of “redeveloping” Vinegar Hill. Most of the city’s African-American residents could not vote in that referendum, thanks to a longstanding, racist poll tax. On June 14, 1960, the referendum narrowly passed, and by 1964 a plan was in place to bulldoze the entire neighborhood. Despite sustained opposition from African-American residents and their allies, in 1965 the neighborhood was razed, and most of its residents displaced to the city’s newly constructed Westhaven public housing project. Federal law required that the city provide such housing for residents it was displacing, although of course a unit in a project is no equivalent to a single-family home. Moreover, Westhaven was apparently as shoddily constructed as many of the era’s public housing projects, and by the 1980s many of its buildings were deteriorating.

Physician Mindy Thompson Fullilove has coined the term “root shock” to describe “the consequences of African American dispossession.” That shock, like the dispossession and destruction that cause it, is a purposeful and indeed central goal of white supremacy: to not only uproot American communities of color, but to make it impossible for those communities to endure as part of the civic life of cities and of the United States. Erased from both the landscape and memory, absent from both narratives of the past and visions of shared futures, these communities would too often, as Fullilove traces, experience “a profound shift in [their] political and social engagement” with both their local worlds and the nation.

That’s the crucial, tragic irony of white supremacist, exclusionary visions of America — in service of a mythic definition of a homogenous nation that never was, they seek to destroy the thriving, inclusive communities that truly define our shared identity. As I argue throughout my new book, We the People: The 500-Year Battle over Who is American, countering those exclusions requires acknowledging the communities and histories that exemplify an inclusive America. On the two-year anniversary of the Charlottesville white supremacist rally, remembering both enslaved laborers and the Vinegar Hill neighborhood would be a fitting response indeed.

Featured image: White supremacists clash with police in Charlottesville, VA, on August 12, 2017 (Evan Nesterak, Wikimedia Commons, via the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

“That Greek Dog” by MacKinlay Kantor

The war correspondent and author MacKinlay Kantor wrote several novels on the American Civil War, like Gettysburg and his Pulitzer Prize-winning Andersonville. He also wrote crime stories, having gotten his start in pulp magazines. His story “That Greek Dog” looks at a small Midwestern town in the 1920s as its people grapple with a rising hate group.

Published on August 9, 1941

“He received . . . praise that will never die, and with it the grandest of all sepulchers, not that in which his mortal bones are laid, but a home in the minds of men.”

-Thucydides (more or less).

In those first years after the first World War, Bill Barbilis could still get into his uniform; he was ornate and handsome when he wore it. Bill’s left sleeve, reading down from the shoulder, had patches and patterns of color to catch any eye. At the top there was an arc — bent stripes of scarlet, yellow and purple; next came a single red chevron with the apex pointing up; and at the cuff were three gold chevrons pointing the other way.

On his right cuff was another gold chevron, only slightly corroded. And we must not forget those triple chevrons on an olive-drab field which grew halfway up the sleeve.

People militarily sophisticated, there in Mahaska Falls, could recognize immediately that Mr. Basilio Barbilis had been a sergeant, that he had served with the Forty-second Division, that he had been once wounded, that he had sojourned overseas for at least eighteen months, and that he had been discharged with honor.

His khaki blouse, however, was worn only on days of patriotic importance. The coat he donned at other times was white — white, that is, until cherry sirup and caramel speckled it. Mr. Barbilis was owner, manager and staff of the Sugar Bowl.

He had a soda fountain with the most glittering spigots in town. He had a bank of candy cases, a machine for toasting sandwiches, ten small tables complete with steel-backed chairs, and a ceiling festooned with leaves of gilt and bronze paper.

Beginning in 1920, he had also a peculiar dog. Bill’s living quarters were in the rear of the Sugar Bowl, and the dog came bleating and shivering to the Barbilis door one March night. The dog was no larger than a quart of ice cream and, Bill said, just as cold.

My medical office and apartment were directly over the Sugar Bowl. I made the foundling’s acquaintance the next day, when I stopped in for a cup of chocolate. Bill had the dog bedded in a candy carton behind the fountain; he was heating milk when I came in, and wouldn’t fix my chocolate until his new pet was fed.

Bill swore that it was a puppy. I wasn’t so certain. It looked something like a mud turtle wearing furs.

“I think he is hunting dog,” said Bill, with pride. “He was cold last night, but not so cold now. Look, I make him nice warm bed. I got my old pajamas for him to lie on.”

He waited upon the sniffling little beast with more tender consideration than ever he showed to any customer. Some people say that Greeks are mercenary. I don’t know. That puppy wasn’t paying board.

The dog grew up, burly and quizzical. Bill named him Duboko. It sounded like that; I don’t know how to spell the name correctly, nor did anyone else in Mahaska Falls.

The word, Bill said, was slang. It meant “tough” or “hard-boiled.” This animal had the face of a clown and the body of a hyena. Growing up, his downy coat changing to wire and bristles, Duboko resembled a fat Hamburg steak with onions which had been left too long on the griddle.

At an early age, Duboko began to manifest a violent interest in community assemblage of any kind or color. This trait may have been fostered by his master, who was proud to be a Moose, an Odd Fellow, a Woodman, and an upstanding member of the Mahaska Falls Commercial League.

When we needed the services of a bugler in our newly formed American Legion post and no bona fide bugler would volunteer, Bill Barbilis agreed to purchase the best brass instrument available and to practice in the bleak and cindery space behind his store. Since my office was upstairs, I found no great satisfaction in Bill’s musical enterprise. It happened that Duboko also lent his voice in support; a Greek chorus, so to speak, complete with strophe and antistrophe.

Nevertheless, I could register no complaint, since with other members of the Legion I had voted to retain Bill as our bugler. I could not even kick Duboko downstairs with my one good leg when I discovered him in my reception room lunching off my mail.

Indeed, most people found it hard to punish Duboko. He had the ingratiating, hopeful confidence of an immigrant just off the boat and assured that he had found the Promised Land. He boasted beady eyes, lubberly crooked paws, an immense mouth formed of black rubber, and pearly and enormous fangs which he was fond of exhibiting in a kind of senseless leer. He smelled, too. This characteristic I called sharply to the attention of his master, with the result that Duboko was laundered weekly in Bill’s uncertain little bathtub, the process being marked by vocal lament which might have arisen from the gloomiest passage of the Antigone.

Mahaska Falls soon became aware of the creature, in a general municipal sense, and learned that it had him to reckon with. Duboko attended every gathering at which six or more people were in congregation. No fire, picnic, memorial service, Rotary conclave or public chicken-pie supper went ungraced by his presence.

If, as sometimes happened on a crowded Saturday night, a pedestrian was brushed by a car, Duboko was on the scene with a speed to put the insurance-company representatives to shame. If there was a lodge meeting which he did not visit and from which he was not noisily ejected, I never heard of it. At Commercial League dinners he lay pensive with his head beneath the chair of Bill Barbilis. But, suffering fewer inhibitions than his master, he also visited funerals, and even the marriage of Miss Glaydys Stumpf.

Old Charles P. Stumpf owned the sieve factory. He was the richest man in town; the nuptials of his daughter exuded an especial aura of social magnificence. It is a matter of historical record that Duboko sampled the creamed chicken before any of the guests did; he was banished only after the striped and rented trousers of two ushers had undergone renting in quite another sense of the word. Grieved, Duboko forswore the Stumpfs after that; he refused to attend a reception for the bride and bridegroom when they returned from the Wisconsin Dells two weeks later.

There was one other place in town where Duboko was decidedly persona non grata. This was a business house, a rival establishment of the Sugar Bowl, owned and operated by Earl and John Klugge. The All-American Kandy Kitchen, they called it.

The Brothers Klugge held forth at a corner location a block distant from the Sugar Bowl. Here lounged and tittered ill-favored representatives of the town’s citizenry; dice rattled on a soiled mat at the cigar counter; it was whispered that refreshment other than soda could be purchased by the chosen.

The business career of Earl and John Klugge did not flourish, no matter what inducement they offered their customers. Loudly they declared that their failure to enrich themselves was due solely to the presence in our community of a Greek — a blackhaired, dark-skinned Mediterranean who thought nothing of resorting to the most unfair business practices, such as serving good fudge sundaes, for instance, to anyone who would buy them.

One fine afternoon people along the main street were troubled at observing Duboko limp rapidly westward, fairly wreathed in howls. Bill called me down to examine the dog. Duboko was only bruised, although at first I feared that his ribs were mashed on one side. Possibly someone had thrown a heavy chair at him. Bill journeyed to the Clive Street corner with fire in his eye. But no one could be found who would admit to seeing an attack on Duboko; no one would even say for a certainty that Duboko had issued from the doorway of the All-American Kandy Kitchen, although circumstantial evidence seemed to suggest it.

Friends dissuaded Bill Barbilis from invading the precinct of his enemies, and at length he was placated by pleasant fiction about a kicking horse in the market square.

We all observed, however, that Duboko did not call at the Kandy Kitchen again, not even on rare nights when the dice rattled loudly and when the whoops and catcalls of customers caused girls to pass by, like pretty Levites, on the other side.

There might have been a different tale to tell if this assault had come later, when Duboko was fully grown. His frame stretched and extended steadily for a year; it became almost as mighty as the earnest Americanism of his master. He was never vicious. He was never known to bite a child. But frequently his defensive attitude was that of a mother cat who fancies her kitten in danger; Duboko’s hypothetical kitten was his right to be present when good fellows — or bad — got together.

Pool halls knew him; so did the Epworth League. At football games an extra linesman was appointed for the sole purpose of discouraging Duboko’s athletic ardor. Through some occult sense, he could become aware of an approaching festivity before even the vanguard assembled. Musicians of our brass band never lugged their instruments to the old bandstand in Courthouse Park without finding Duboko there before them, lounging in an attitude of expectancy. It was Wednesday night, it was eight o’clock, it was July; the veriest dullard might know at what hour and place the band would begin its attack on the Light Cavalry Overture.

Duboko’s taste in music was catholic and extensive. He made a fortuitous appearance at a spring musicale, presented by the high-school orchestra and glee clubs, before an audience which sat in the righteous hush of people grimly determined to serve the arts, if only for a night.

The boys’ glee club was rendering selections from Carmen — in English, of course — and dramatically they announced the appearance of the bull. The line goes, “Now the beast enters, wild and enraged,” or something like that; Duboko chose this moment to lope grandly down the center aisle on castanetting toenails. He sprang to the platform … Mahaska Falls wiped away more tears than did Mérimée’s heroine.

In his adult stage, Duboko weighed forty pounds. His color suggested peanut brittle drenched with chocolate; I have heard people swear that his ears were four feet long, but that is an exaggeration. Often those ears hung like limp brown drawers dangling from a clothesline; again they were braced rigidly atop his skull.

Mastiff he was, and also German shepherd, with a noticeable influence of English bull, bloodhound and great Dane. Far and wide he was known as “that Greek dog,” and not alone because he operated out of the Sugar Bowl and under the aegis of Bill Barbilis. Duboko looked like a Greek.

He had Greek eyes, Greek eyebrows, and a grinning Greek mouth. Old Mayor Wingate proclaimed in his cups that, in fact, he had heard Duboko bark in Greek; he was willing to demonstrate, if anyone would only catch Duboko by sprinkling a little Attic salt on his tail.

That Greek dog seldom slept at night; he preferred to accompany the town’s watchman on his rounds, or to sit in the window of the Sugar Bowl along with cardboard ladies who brandished aloft their cardboard sodas. Sometimes, when I had been called out in the middle of the night and came back from seeing a patient, I would stop and peer through the window and exchange a few signals with Duboko.

“Yes,” he seemed to say, “I’m here. Bill forgot and locked me in. I don’t mind, unless, of course, there’s a fire. See you at Legion meeting tomorrow night, if not at the County Medical Association luncheon tomorrow noon.”

At this time there was a new arrival in the Sugar Bowl household — Bill’s own father, recruited all the way from Greece, now that Bill’s mother was dead.

Spiros Barbilis was slight, silver-headed, round-shouldered, with drooping mustachios which always seemed oozing with black dye. Bill put up another cot in the back room and bought another chiffonier from the secondhand store. He and Duboko escorted the old man up and down Main Street throughout the better part of one forenoon.

“I want you to meet friend of mine,” Bill said. “He is my father, but he don’t speak no English. I want him to meet all my good friends here in Mahaska Falls, because he will live here always.”

Old Mr. Barbilis grew deft at helping Bill with the Sugar Bowl. He carried trays and managed tables, grinning inveterately, wearing an apron stiff with starch. But he failed to learn much English except “hello” and “goodbye” and a few cuss words; I think that he was lonely for the land he had left, which certainly Bill was not.

One night — it was two o’clock in the morning — I came back to climb my stairs, stepping carefully from my car to the icy sidewalk in front of the Sugar Bowl. I moved gingerly, because I had left one foot in the Toul sector when a dressing station was shelled; I did not like icy sidewalks.

This night I put my face close to the show window to greet Duboko, to meet those sly and mournful eyes which, on a bitter night, would certainly be waiting there instead of shining in a drifted alley where the watchman prowled.

Two pairs of solemn eyes confronted me when I looked in. Old Mr. Barbilis sat there, too — in his night clothes, but blanketed with an overcoat — he and Duboko, wrapped together among the jars of colored candy and the tinted cardboard girls. They stared out, aloof and dignified in the darkness, musing on a thousand lives that slept nearby. I enjoy imagining that they both loved the street, even in its midnight desertion, though doubtless Duboko loved it the more.

In 1923 we were treated to a mystifying phenomenon. There had never been a riot in Mahaska Falls, nor any conflict between racial and religious groups. Actually we had no racial or religious groups; we were all Americans, or thought we were. But, suddenly and amazingly, fiery crosses flared in the darkness of our pasture lands.

I was invited to attend a meeting and did so eagerly, wondering if I might explore this outlandish nonsense in a single evening. When my car stopped at a cornfield gate and ghostly figures came to admit me, I heard voice after voice whispering bashfully, “Hello, doc,” “Evening, doc. Glad you came.” I was shocked at recognizing the voices. I had known the fathers and grandfathers of these youths — hard-working farmers they were, who found a long-sought freedom on the American prairies, and never fumed about the presence of the hard-working Catholics, Jews and black men who were also members of that pioneer community.

There was one public meeting in the town itself. They never tried to hold another; there was too much objection; the voice of Bill Barbilis rang beneath the stars.

A speaker with a pimply face stood illuminated by the flare of gasoline torches on a makeshift rostrum, and dramatically he spread a dollar bill between his hands. “Here,” he cried, “is the flag of the Jews!”

Bill Barbilis spoke sharply from the crowd: “Be careful, mister. There is United States seal on that bill.”

In discomfiture, the speaker put away his bank note. He ignored Bill as long as he could. He set his own private eagles to screaming, and he talked of battles won, and he wept for the mothers of American boys who lay in France. He said that patriotic 100 per cent Americans must honor and protect those mothers.

Bill Barbilis climbed to the fender of a car. “Sure,” he agreed clearly, “we got to take care of those mothers! Also, other mothers we got to take care of — Catholic mothers, Greek mothers, Jew mothers. We got the mothers of Company C, One Hundred Sixty-eighth Infantry. We got to take care of them. How about Jimmy Clancy? He was Catholic. He got killed in the Lorraine sector. Hyman Levinsky, he got killed the same day. Mr. Speaker, you don’t know him because you do not come from Mahaska Falls. We had Buzz Griffin, colored boy used to shine shoes. He go to Chicago and enlist, and he is wounded in the Ninety-second Division!”

It was asking too much for any public speaker to contend against opposition of that sort; and the crowd thought so, too, and Duboko made a joyful noise. The out-of-town organizers withdrew. Fiery crosses blazed less frequently, and the flash of white robes frightened fewer cattle week by week.

Seeds had been sown, however, and now a kind of poison ivy grew within our midnight. Bill Barbilis and Duboko came up to my office one morning, the latter looking annoyed, the former holding a soiled sheet of paper in his hand. “Look what I got, doc.”

The message was printed crudely in red ink:

We don’t want you here anymore. This town is only for 100 per cent law-abiding white Americans. Get out of town! Anti-Greek League.

It had been shoved under the front door of the Sugar Bowl sometime during the previous night.

“Bill,” I told him, “don’t worry about it. You know the source, probably; at least you can guess.”

“Nobody is going to run me out of town,” said Bill. “This is my town, and I am American citizen, and I am bugler in American Legion. I bring my old father here from Greece to be American, too, and now he has first papers.” His voice trembled slightly.

“Here. Throw it in the wastepaper basket and forget about it.”

There was sweat on his forehead. He wiped his face, and then he was able to laugh. “Doc, I guess you are right. Doc, I guess I am a fool.”

He threw the paper away and squared his shoulders and went downstairs. I rescued a rubber glove from Duboko and threw Duboko into the hall, where he licked disinfectant from his jaws and leered at me through the screen.

A second threatening letter was shoved under Bill’s door, but after that old Mr. Spiros Barbilis and Duboko did sentry duty, and pedestrians could see them entrenched behind the window. So the third warning came by mail: it told Bill that he was being given twenty-four hours to get out of town for good.

I was a little perturbed when I found Bill loading an Army .45 behind his soda fountain.

“They come around here,” he said, “and I blow hell out of them.”

He laughed when he said it, but I didn’t like the brightness of his eyes, nor the steady, thrice-assured activity of his big clean fingers.

On Friday morning Bill came up to my office again; his face was distressed. But my fears, so far as the Anti-Greeks were concerned, were groundless.

“Do you die,” he asked, “when you catch a crisis of pneumonia?”

It was one of his numerous cousins, in Sioux Falls. There had been a long-distance telephone call; the cousin was very ill, and the family wanted Bill to come. Bill left promptly in his battered, rakish roadster.

Late that night I was awakened by a clatter of cream cans under my window. I glanced at the illuminated dial of my watch, and lay wondering why the milkman had appeared some two hours before his habit. I was about to drop off to sleep when sounds of a scuffle in the alley and a roar from Duboko in the Barbilis quarters took me to the window in one leap.

There were four white figures down there in the alley yard; they dragged a fifth man — night-shirted, gagged, struggling — along with them. I yelled, and pawed around for my glasses, spurred to action by the reverberating hysterics of Duboko. I got the glasses on just before those men dragged old Mr. Barbilis into their car. The car’s license plates were plastered thick with mud; at once I knew what had happened.

It was customary for the milkman to clank his bottles and cans on approaching the rear door of the Sugar Bowl; Bill or his father would get out of bed and fetch the milk to the refrigerator, for there were numerous cream-hungry cats along that alley. It was a clinking summons of this sort which had lured the lonely Mr. Barbilis from his bed.

He had gone out sleepily, probably wondering, as I had wondered, why the milkman had come so early. The sound of milk bottles lulled Duboko for a moment.

Then the muffled agony of that struggle, when the visitors clapped a pillow over the old man’s face, had been enough to set Duboko bellowing.

But he was shut in; all that he could do was to threaten and curse and hurl himself against the screen. I grabbed for my foot — not the one that God gave me, but the one bought by Uncle Sam — and of course I kicked it under the bed far out of reach.

My car was parked at the opposite end of the building, out in front. I paused only to tear the telephone receiver from its hook and cry to a surprised Central that she must turn on the red light which summoned the night watchman; that someone was kidnaping old Mr. Barbilis.

The kidnapers’ car roared eastward down the alley while I was bawling to the operator. And then another sound — the wrench of a heavy body sundering the metal screening. There was only empty silence as I stumbled down the stairway in my pajamas, bouncing on one foot and holding to the stair rails.

I fell into my car and turned on the headlights. The eastern block before me stretched deserted in the pale glow of single bulbs on each electric-light post. But as my car rushed into that deserted block, a small brown shape sped bulletlike across the next intersection. It was Duboko.

I swung right at the corner, and Duboko was not far ahead of me now. Down the dark, empty tunnel of Clive Street the red taillight of another car diminished rapidly. It hitched away to the left; that would mean that Mr. Barbilis was being carried along the road that crossed the city dump.

Slowing down, I howled at Duboko when I came abreast of him. It seemed that he was a Barbilis, an Americanized Greek, like them, and that he must be outraged at this occurrence, and eager to effect a rescue.

But he only slobbered up at me, and labored along on his four driving legs, with spume flying behind. I stepped on the gas again and almost struck the dog, for he would not turn out of the road. I skidded through heavy dust on the dump lane, with filmier dust still billowing back from the kidnapers’ car.

For their purpose, the selection of the dump had a strategic excuse as well as a symbolic one. At the nearest boundary of the area there was a big steel gate and barbed-wire fence; you had to get out and open that gate to go through. But if you wished to vanish into the region of river timber and country roads beyond, you could drive across the wasteland without opening the gate again. I suppose that the kidnapers guessed who their pursuer was; they knew of my physical incapacity. They had shut the gate carefully behind them, and I could not go through it without getting out of my car.

But I could see them in the glare of my headlights — four white figures, sheeted and hooded.

Already they had tied Spiros Barbilis to the middle of a fence panel. They had straps, and a whip, and everything else they needed. One man was tying the feet of old Spiros to restrain his kicks; two stood ready to proceed with the flogging; and the fourth blank, hideous, white-hooded creature moved toward the gate to restrain me from interfering. That was the situation when Duboko arrived.

I ponder now the various wickednesses Duboko committed throughout his notorious career. Then for comfort I turn to the words of a Greek — him who preached the most famous funeral oration chanted among the ancients — the words of a man who was Greek in his blood and his pride, and yet who might have honored Duboko eagerly when the dog came seeking, as it were, a kind of sentimental Attican naturalization.

“For even when life’s previous record showed faults and failures,” said Pericles, with the voice of Thucydides, to the citizens of the fifth century, “it is just to weigh the last brave hour of devotion against them all.”

Though it was not an hour by any means. No more than ten minutes had elapsed since old Mr. Barbilis was dragged from his backyard. The militant action of Duboko, now beginning, did not occupy more than a few minutes more, at the most. It makes me wonder how long men fought at Marathon, since Pheidippides died before he could tell.

And not even a heavy screen might long contain Duboko; it is no wonder that a barbed-wire fence was as reeds before his charge.

He struck the first white figure somewhere above the knees. There was a snarl and a shriek, and then Duboko was springing toward the next man.

I didn’t see what happened then. I was getting out of the car and hopping toward the gate. My bare foot came down on broken glass, and that halted me for a moment. The noise of the encounter, too, seemed to build an actual, visible barrier before my eyes.

Our little world was one turmoil of flapping, torn white robes — a whirling insanity of sheets and flesh and outcry, with Duboko revolving at the hub. One of the men dodged out of the melee, and stumbled back, brandishing a club which he had snatched from the rubble close at hand. I threw a bottle, and I like to think that that discouraged him; I remember how he pranced and swore.

Mr. Barbilis managed to get the swathing off his head and the gag out of his mouth. His frail voice sang minor encouragement, and he struggled to unfasten his strapped hands from the fence.

The conflict was moving now — moving toward the kidnapers’ car. First one man staggered away, fleeing; then another who limped badly. It was an unequal struggle at best. No four members of the Anti-Greek League, however young and brawny, could justly be matched against a four-footed warrior who used his jaws as the original Lacedaemonians must have used their daggers, and who fought with the right on his side, which Lacedaemonians did not always do.

Four of the combatants were scrambling into their car; the fifth was still afoot and reluctant to abandon the contest. By that time I had been able to get through the gate, and both Mr. Barbilis and I pleaded with Duboko to give up a war he had won. But this he would not do; he challenged still, and tried to fight the car; and so, as they drove away, they ran him down.

It was 10 a.m. before Bill Barbilis returned from Sioux Falls. I had ample opportunity to impound Bill’s .45 automatic before he came.

His father broke the news to him. I found Bill sobbing with his head on the fountain. I tried to soothe him, in English, and so did Spiros Barbilis, in Greek; but the trouble was that Duboko could no longer speak his own brand of language from the little bier where he rested.

Then Bill went wild, hunting for his pistol and not being able to find it; all the time, his father eagerly and shrilly informed Bill of the identifications he had made when his assailants’ gowns were ripped away. Of course, too, there was the evidence of bites and abrasions.

Earl Klugge was limping as he moved about his All-American Kandy Kitchen, and John Klugge smelled of arnica and iodine. A day or two passed before the identity of the other kidnapers leaked out. They were hangers-on at the All-American; they didn’t hang on there any longer.

I should have enjoyed seeing what took place, down there at the Clive Street corner. I was only halfway down the block when Bill threw Earl and John Klugge through their own plateglass window.

A little crowd of men gathered, with our Mayor Wingate among them. There was no talk of damages or of punitive measures to be meted out to Bill Barbilis. I don’t know just what train the Klugge brothers left on. But their restaurant was locked by noon, and the windows boarded up.

A military funeral and interment took place that afternoon behind the Sugar Bowl. There was no flag, though I think Bill would have liked to display one. But the crowd of mourners would have done credit to Athens in the age when her dead heroes were burned; all the time that Bill was blowing Taps on his bugle, I had a queer feeling that the ghosts of Pericles and Thucydides were somewhere around.

Order a copy of The Saturday Evening Post: A Celebration of Dogs! for more stories of helpful and heroic mutts.

Order a copy of The Saturday Evening Post: A Celebration of Dogs! for more stories of helpful and heroic mutts.Featured image: Illustration by John F. Gould

Considering History: The Role of Women in the Lynching Epidemic

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On February 14, Senator Kamala Harris introduced legislation into the Senate that would for the first time in American history make lynching a federal crime. The Justice for Victims of Lynching Act, originally drafted by Harris in June 2018, does more than just criminalize lynching—as its name suggests, it seeks to remember and in some small ways make amends for the thousands of lynchings that took place between the end of the Civil War and the 1960s. “With this bill,” Harris said, “we finally have a chance to speak the truth about our past and make clear that these hateful acts should never happen again. We can finally offer some long overdue justice and recognition to the victims of lynching and their families.”

The horrific stories of lynching are intimately intertwined with African American history, a significant factor in Harris’s choice to introduce the bill during Black History Month. Yet as with any American histories, lynching’s connections extend to every national community. For Women’s History Month, Harris’s prominent role in these unfolding 21st century accounts can also help us remember the fraught, contradictory, and crucial links between American women and the lynching epidemic.

Perhaps the single most jarring defense of lynching was offered by a pioneering feminist activist. Rebecca Ann Latimer Felton, the wife and political partner of longtime Georgia Congressman William Harrell Felton, was one of the Progressive Era’s most prominent and acclaimed women’s rights activists: an advocate of women’s suffrage, equal pay, and many other feminist causes, she became the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate when, at the age of 87, she was honored with a single-day appointment as Senator from Georgia on November 21, 1922. Yet she was also a white supremacist and racist who openly advocated for the systematic lynching of African Americans.

Felton made her case for lynching most vocally in an August 1897 speech to the Georgia Agricultural Society. While she identified a number of problems facing (white) farm wives in the state, she focused in particular on “the black rapist” and the threat he posed to those women. She repeated the canard that Reconstruction had given African Americans “license to degrade and debauch.” And in response to those imagined terrors, she argued, “When there is not enough religion in the pulpit to organize a crusade against sin; nor justice in the court house to promptly punish crime; nor manhood enough in the nation to put a sheltering arm about innocence and virtue—if it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession form the ravening human beasts—then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary.”

Felton’s bigoted speech reminds us that the era’s progressive white women far too often allied with the forces of segregation and white supremacy, both to further their movement’s goals and (as in Felton’s case to be sure) out of genuine and deeply rooted racism. Yet as historian Martha Jones has recently argued, the under-appreciated contributions of African American women to the women’s suffrage movement played a crucial role in advancing women’s right to vote. One of the most prominent such African American suffrage activists, Ida B. Wells, also happened to be the nation’s leading anti-lynching journalist and crusader.

The opening pages of Wells’s first book, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892), reflect the intersections of her women’s rights and anti-lynching activism. In her preface, Wells acknowledges the fundraising efforts of New York City women’s rights organizations that allowed her to publish the book, writing, “the noble effort of the ladies of New York and Brooklyn Oct. 5 have enabled me to comply with this request and give the world a true, unvarnished account of the causes of lynch law in the South.” Wells highlights both her own status as a target of white supremacist violence (when her Memphis newspaper office was burned down) and her courageous response to those attacks: “Since my business has been destroyed and I am an exile from home because of that editorial, the issue has been forced, and as the writer of it I feel that the race and the public generally should have a statement of the facts as they exist.” As an African American woman speaking out against these horrors, she likewise revises Felton’s images of race and gender, noting, “[The facts] will serve at the same time as a defense for the Afro-Americans Sampsons who suffer themselves to be betrayed by white Delilahs.”

While reports of lynching usually involved African American male victims, the epidemic also extended to other communities of color, including Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. A recent New York Times article that highlights the histories of Mexican American lynchings in particular reveals another role for American women activists: as contributors to expanded collective memories. That includes the historians upon whose work that New York Times article depends: Professors Monica Muñoz Martínez of Brown University and Laura F. Edwards of Duke University. But it also includes women like Arlinda Valencia, the Texas educator and union official whose ancestors were among the victims of the January 1918 Porvenir mass lynching in which Texas Rangers and ranchers destroyed an entire Mexican American village.

Professor Martínez’s educational nonprofit organization Refusing to Forget has in the half-dozen years since its founding done particularly impressive work recovering those histories and sharing them with audiences of all types. Those efforts include historical markers for particular sites such as Porvenir, traveling and permanent museum exhibitions, and public lectures and conversations. Martínez and her colleagues have discovered a pattern of widespread violence directed not only at individual Mexican Americans, but also and especially at entire communities, with the Porvenir massacre sadly not atypical of these outbursts of collective brutality.

Like Senator Harris, these scholarly and civic historians are working to make the lynching epidemic’s histories more consistently present in our 21st century collective memories. Doing so likewise requires remembering lynching’s complex intersections of race and gender, both in their most destructive and most inspiring forms.

Featured image: The Silent Parade in 1917 in New York City was organized by the NAACP to protest violence toward African Americans. (Library of Congress)

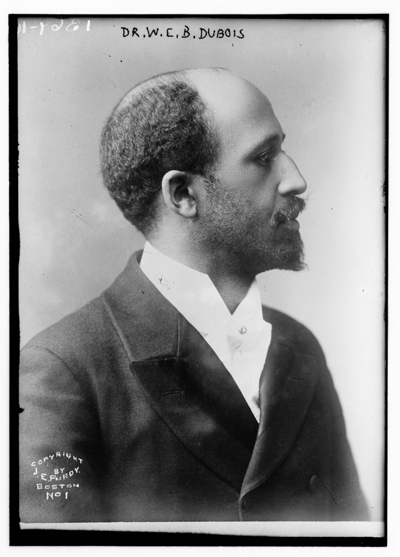

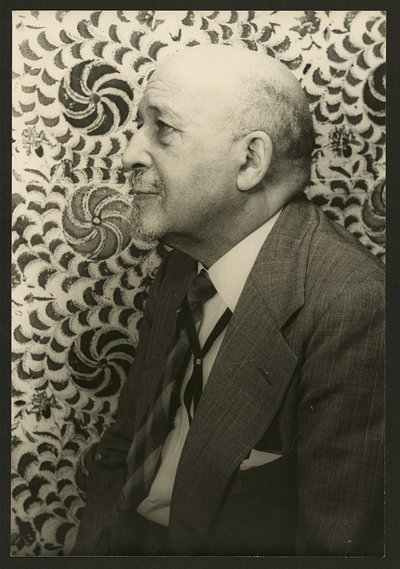

Considering History: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Urgent Lessons of History

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On February 23, 1868, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. The only child of mixed-race parents who separated when he was two, Du Bois was raised by his single mother Mary and her parents and family, experiencing this integrated community and school system as one of the town’s only African American residents. He left Great Barrington in 1885 to attend Nashville’s historically black Fisk University, and then pursued further studies at Harvard College, the University of Berlin, and back to Harvard University where he became in 1895 the first African American to receive a PhD (in History). He would spend his remaining seven decades becoming one of America’s and the world’s foremost historians, journalists, educators, writers, activists, and public figures, passing away in Ghana the day before the August 1963 March on Washington.

Those details only scratch the surface of the life, career, and impact of this towering figure, and he rewards further research and reading. But to celebrate the joint occasion of Du Bois’s 151st birthday and the last week of Black History Month, it’s worth taking a step back to consider a few of the many ways that Du Bois’s work and words resonate with our contemporary moment, offering urgent lessons for America and the world in 2019.

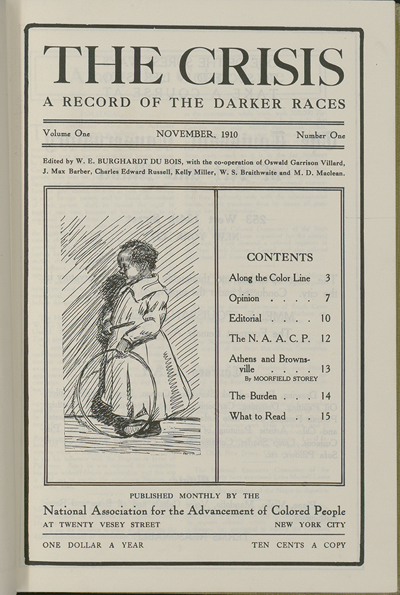

In 1910, Du Bois helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and became its first director of publicity and research. In that role he founded and for many years edited the NAACP’s monthly magazine The Crisis, contributing thoughtful and impassioned editorials on many of the era’s most significant issues. In one such editorial, “Returning Soldiers” (May 1919), Du Bois highlighted the irony of African American World War I veterans returning home to face racist discrimination and violence in the U.S., and advocated for patriotic activism in response to those horrors:

But, by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land. We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.

All too often, the antiracist protests of Colin Kaepernick, #BlackLivesMatter, and their activist peers are framed in opposition to both the military and American patriotic ideals. Yet so many moments in history, from U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War to Jackie Robinson’s World War II sit-in for military integration, highlight the inescapable interconnections between African American activists, military service, and the nation’s highest ideals and darkest realities. Du Bois’s stirring words help us consider Kaepernick and #BLM as part of this legacy, rather than as critics of it.

In July 1930, Du Bois returned to Great Barrington to give a speech to the Searles High School Alumni Association. He chose to focus on the school’s relationship to the neighboring Housatonic River:

It may be that some thoughtful person saw far beyond the present and grasped the idea that they were putting the institution on what was the natural great highway of the valley. They may have looked forward to the time when parks and boulevards would line the redeemed river; when the best people would not attempt to climb the hills to get away from the valley, but turn about and descend to its gracious invitation; when public buildings and canoes and pleasure boats and swimming children would make the whole valley glad and the river would come into its own again. … With this beginning we may in time clear the river, give the Searles High school its perfect setting. We may even induce the mills (if we can find out who owns them) to stop pouring their refuse into the river, which is merely a habit and not a necessity. … And so I have ventured to call the attention of the graduates of the Searles High School to this bit of philosophy of living in this valley, urging that we should rescue the Housatonic and clean it as we have never in all the years thought before of cleaning it, and seek to restore its ancient beauty; making it the center of a town, of a valley, and perhaps — who knows? — of a new measure of civilized life.

While the environmental movement has evolved significantly over the last few decades, perspectives on environmental activism and justice continue to define this work as separate from our shared human communities and histories. But as Du Bois here reminds his fellow Searles graduates, the story, history, and future of our rivers (and our environment in every sense) are intertwined with those of our schools and our children, our towns and our societies. Such lessons have never been more relevant than in these pivotal remaining years to combat and reverse global climate change.

Despite these and many other diverse and deep interests, however, Du Bois was first and foremost a historian. In 1936 he published his best scholarly work, and one of the most ground-breaking and influential historiographic texts in American history: Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. Black Reconstruction influenced both the specific scholarly conversations and the discipline of history in multiple ways, from Du Bois’s archival research process to his challenging and compelling conclusions.

But the book’s stand-out section is its last chapter, “The Propaganda of History,” where Du Bois traces the development (in educational textbooks, academic scholarship, and popular culture) of false and destructive narratives of post-Civil War history. Some of the most damning such narratives were those that depicted African Americans as so ignorant and savage that they thoroughly abused their new freedoms, as illustrated by entirely manufactured images (including a sequence in the 1915 blockbuster film Birth of a Nation) of the first African American elected officials holding raucous and lewd parties on the floors of state legislatures throughout the South. “It is propaganda like this,” Du Bois writes, “that has led men in the past to insist that history is ‘lies agreed upon’; and to point out the danger in such misinformation. It is indeed extremely doubtful if any permanent benefit comes to the world through such action. Nations reel and stagger on their way; they make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as the truth is ascertainable?”

Du Bois’s thorough documentation and debunking of this propagandistic vision of post-Civil War American history is most overtly relevant to our debate over Confederate memorials and memory. Constructed in the early 20th century, the same era in which that Dunning School narrative of Reconstruction was taking hold throughout educational and cultural settings, these Confederate monuments truly represent lies agreed upon, misrepresentations of both the causes and enduring effects of the Civil War and the Confederacy. We have yet to tell the truth about their histories in our collective conversations.

Yet Du Bois’s chapter also makes the case for remembering a nation’s “great and beautiful things,” not in opposition to such dark histories but in direct relationship to them. In the final paragraphs of his magisterial book The Souls of Black Folk (1903), he highlights one such great and beautiful thing: the contribution of African Americans to every stage and element of American identity. There’s no better way to end a commemoration of Du Bois’s birthday and Black History Month than with those stirring concluding worlds: “Our song, our toil, our cheer, and warning have been given to this nation in blood-brotherhood. Are not these gifts worth the giving? Is not this work and striving? Would America have been America without her Negro people?”

Featured image: Library of Congress

Considering History: Blackface’s Inescapable Stain on American Culture

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Incidents and images of blackface have dominated the last week’s news cycle. As of this writing at least three prominent Virginia political leaders (the governor, attorney general, and Senate majority leader) have all been tied to the racist practice, as has Mississippi’s lieutenant governor. While those incidents were all in the politicians’ pasts, another shocking scandal reflects blackface’s continued cultural presence, as Gucci was discovered to be marketing a wool sweater clearly intended to echo the most caricatured, extreme blackface images (making it the latest in a series of high-end companies attempting literally to capitalize on blackface in the 21st century).

These incidents have been rightly condemned, and both the politicians and corporations are likely to face significant and deserved consequences for their links to blackface. But it’s vitally important that we not assume blackface is simply a reflection of overt racists or a few bad apples. The racist practice is deeply embedded in American history and culture, and recognizing its sweeping legacies allows us to better understand the presence of bigoted imagery in many of our foundational social systems and cultural forms.

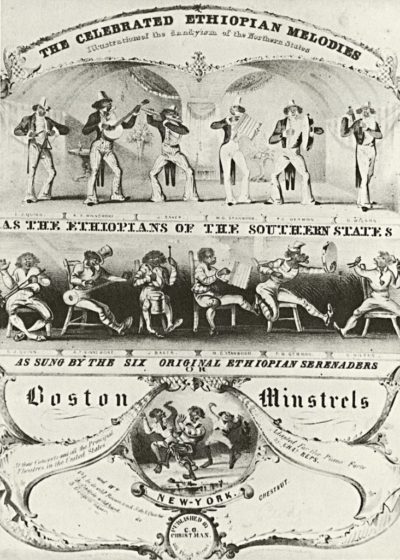

Blackface minstrelsy is one of the oldest American cultural forms. As scholar Eric Lott traces in his magisterial Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (1993), the early 19th century development of minstrel shows represented a strikingly unique American innovation on longstanding theatrical genres like comedy and the burlesque. Most of the era’s most prominent stage actors, from Edwin Forrest to George Washington Dixon, specialized in performing as blackface characters like the ubiquitous “Sambo,” building both their individual reputations and American theater’s exploding popularity around these caricatured characters.

In 1828, New York comic performer Thomas Dartmouth (T.D.) Rice (known professionally as “Daddy Rice”) debuted a new such blackface character, Jim Crow, in the song-and-dance number “Jump Jim Crow.” The act became such a national (and eventually even international) sensation that a decade later the Boston Post would write, “the two most popular characters in the world at the present time are [Queen] Victoria and Jim Crow.” Ironically but tellingly, Rice’s humorous fictional character would become a focal image through which white supremacists could mock, stereotype, and oppress African Americans, as exemplified by the direct association of “Jim Crow” with the rise of segregationist and racist laws and social practices throughout the post-Civil War South.

Compared to that direct link between a minstrel character and an entire legal and social system, blackface’s effects on late 19th and 20th century American popular culture were more subtle but just as sweeping. As American theater separated from European traditions and developed its own identity across the 19th century, the most popular and consistently present theatrical works were the Tom Shows, stage productions based on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851). Even before the Civil War, those shows began to transform from abolitionist critiques of slavery (ones based directly on Stowe’s novel) into blackface burlesques. After the war, blackface minstrelsy became the Tom Shows’ dominant mode, and would remain so well into the 20th century. The shows gradually came to feature African American performers in the background (often singing “plantation melodies”), but it was white actors in blackface who embodied such famous, caricatured figures as Tom and Topsy.

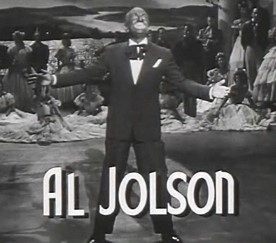

Along with the Tom Shows, another central theatrical trend in turn-of-the-century America were vaudeville shows. These variety shows provided a hugely popular bridge between the theater and the 20th century’s most dominant pop culture forms, including radio, films, and television; indeed, some of the century’s most enduring pop culture figures, such as George Burns, moved directly from vaudeville into those other media. Vaudeville shows usually featured ten or more distinct performers and acts in a variety of styles, but blackface performances were a constant and central presence, often opening and closing the shows as guaranteed crowd pleasers. And virtually all of the most famous vaudeville stars, from Jack Benny to Milton Berle to Laurel and Hardy to George Burns himself, incorporated blackface into their acts.

As vaudeville gradually gave way to the motion picture industry, that 20th century cultural form likewise depended heavily on blackface performances. The first blockbuster silent film, director D.W. Griffith’s controversial mega-hit The Birth of a Nation (1915), featured white actors in blackface in many of its crucial villainous roles. Well before Birth, some of the earliest popular silent films were blackface (or “coon”) comedies like The Wooing and Wedding of a Coon (1907), The Pickaninnies (1908), and The Sambo Series (1909-11). And perhaps most strikingly, the first prominent “talkie” film, 1927’s The Jazz Singer, features Al Jolson as an entertainer who spends much of the film (including its triumphant finale) in blackface, cementing the central role of blackface to the evolution of American film across each of its foundational periods.

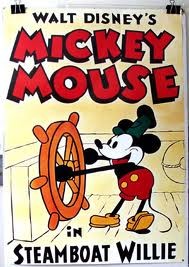

Just a year after Jolson sang his way into history, the Disney Animation Studios character Mickey Mouse made his debut, in 1928’s Steamboat Willie. As historian Nicholas Sammond traces at length in Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation (2015), foundational animated characters like Mickey (as well as Felix the Cat and Bugs Bunny, among many others) were directly inspired by blackface minstrelsy and vaudeville tropes and images. Mickey’s minstrel influences are particularly clear in such early animations, from his top hat, cane, and white gloves to his exaggerated whistling, dancing, and slapstick humor. And indeed, in 1933 Disney Animation released the short film Mickey’s Mellerdrammer (a caricatured dialect misspelling of “melodrama”) in which Mickey and friends perform their own version of a Tom Show while in blackface.

Yes, even Mickey and Disney are inextricably intertwined with blackface. Those century-old cultural interconnections and influences meant that blackface performance was widely accepted throughout much of the 20th century, as illustrated by the 1986 teen comedy film Soul Man, in which C. Thomas Howell’s protagonist Mark Watson spends most of the film using blackface to disguise himself as an African American man and benefit from an affirmative action law school admissions program. While the NAACP and other activists challenged blackface’s stereotypes and bigotry throughout those eras, it was only with controversies such as that surrounding Ted Danson in 1993 that widespread cultural critiques of blackface performance emerged. And even as recently as 2015, a Yale administrator emailed students to argue that they should ignore an official request to stay away from blackface in Halloween costumes, reflecting the continued debate into our own moment over this pernicious but longstanding and widespread form of racial performance.

Yes, even Mickey and Disney are inextricably intertwined with blackface. Those century-old cultural interconnections and influences meant that blackface performance was widely accepted throughout much of the 20th century, as illustrated by the 1986 teen comedy film Soul Man, in which C. Thomas Howell’s protagonist Mark Watson spends most of the film using blackface to disguise himself as an African American man and benefit from an affirmative action law school admissions program. While the NAACP and other activists challenged blackface’s stereotypes and bigotry throughout those eras, it was only with controversies such as that surrounding Ted Danson in 1993 that widespread cultural critiques of blackface performance emerged. And even as recently as 2015, a Yale administrator emailed students to argue that they should ignore an official request to stay away from blackface in Halloween costumes, reflecting the continued debate into our own moment over this pernicious but longstanding and widespread form of racial performance.

Blackface’s presence doesn’t mean we have to cancel much of American popular culture—but it does mean that we have to better remember and engage with these widespread, inescapable legacies of blackface minstrelsy across our cultural and social landscapes. Perhaps this moment of heightened attention to the histories of blackface can help us start that long overdue collective reckoning.