Too Old to Be President?

Age has been a big factor in this election.

For the first time, two candidates in their 70s are running for the nation’s highest office. And as you’d expect, both parties are claiming the other’s candidate is feeble, disoriented, and making no sense — i.e., too old for the job.

But 70 years doesn’t mean decrepitude as it once did. “Threescore and ten” years was the lifespan the Bible allotted to a human, but today’s 70-year-olds are different. They’re generally healthier, more active, and less mentally impaired than their parents or grandparents were at that age (if they even reached that age). Can an older candidate be less competent because of age? Certainly. But incompetence can be found in candidates of any age.

Perhaps the concern with age issue is really a concern over health: can a 70-year-old endure the stress that comes with the Oval Office?

The chances are good for either candidate because presidents appear to be unusually hardy.

For example, the Republican Party tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1948. He turned them down, concluding he would be unelectable. They expected Thomas Dewey — the candidate they chose instead — to serve two terms. Which would make Eisenhower 66 years old if he chose to serve in 1956, and the country wouldn’t want someone that old.

But Eisenhower ran in 1951 and won. Three years later, he had a heart attack, but entered the race again in 1955, and won again. After he left the White House, he continued to play a dominant role in the Republican party until he passed away at 78.

Gerald Ford was 61 when he assumed the presidency upon Nixon’s resignation in 1974. He lived 29 years more. Ronald Reagan, aged 69 years at his 1981 inauguration, served two terms and lived 16 years beyond that. George H.W. Bush was 64 when he entered the Oval Office in 1989. He lived another 29 years.

And of course, there’s Jimmy Carter, who was elected at the tender age of 52. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still with us, building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

It’s significant that, of the six presidents who have celebrated their 90th birthday, four — Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — served in the past 50 years.

But the number of decades is just one way to consider age. We can also judge a president’s age relative to the average lifespan of his time.

Up to the 1930s, Americans could think themselves lucky if they reached their 65th birthday. But our lifespan has continually lengthened; since 1920, the average American has gained 25 years of life.

Historians have estimated that, in the centuries preceding the 1800s, the average human lived just 35 years. The number is surprisingly low because it is calculated from the ages of all deaths within a year. Nearly half of these deaths (46 percent) were among children under the age of five, which lowered the average age of mortality for adults.

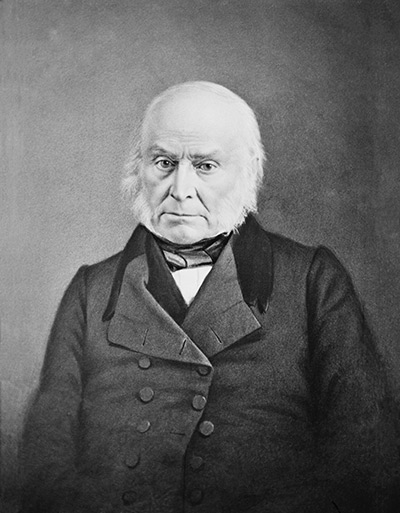

One researcher has concluded that a more realistic average lifespan of a 20-year-old American in 1800 was 47 years — still not a long life. Which is what makes John Adams so exceptional. Adams became president at the age of 61 — fourteen years beyond his expected lifetime. And he lived 25 years beyond his presidency!

Adams’s son, President John Quincy Adams, lived to 80. Thomas Jefferson reached 83, and James Madison saw his 85th birthday.

Today, the average American lives 78.54 years. But an American male who reaches the age of 65, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, has a good chance of living another 19 years.

Which means either candidate might be likely to live to the age of 84 – or beyond.

It’s possible that presidents in their 70s will be looked on more favorably as the proportion of elders in the population increases. By 2060, a quarter of the U.S. population will be over 65 years and old, and the average American lifespan will have risen from 74 to 85 years.

Children today may live to hear candidates someday complain that their 100-year-old opponents are too old to be president.

Featured image: John Adams, Dwight Eisenhower, and Andrew Jackson, three of the older presidents when they assumed office (Adams: National Gallery of Art; Eisenhower: Wikimedia Commons; Jackson: whitehousehistory.org)

Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Hail to the Movie Chiefs

See all Movies for the Rest of Us.

Featured image: Joseph Henabery in The Birth of a Nation

Review: Jimmy Carter: Rock and Roll President — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Jimmy Carter: Rock and Roll President

⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Director: Mary Wharton

Stars: Jimmy Carter, Garth Brooks, Jimmy Buffett, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Larry Gatlin

In theaters and virtual theater video on demand

Bill Clinton may have been the first U.S. President born after World War II, but as this tuneful, nostalgic documentary reminds us, it was Jimmy Carter who first harnessed the energy of rock and roll to catapult himself to the highest office in the land.

James Earl Carter, born in 1924, went to war to the music of Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey — but he was a Georgia boy whose childhood soundtrack was dominated by the gospel tunes he sang in church and the barn dance music that crackled through the air from the Grand Ole Opry.

By the time he ran for President in 1976, Carter’s musical tastes had already morphed into a love of country-tinged rock and roll, and he brought that sensibility to his campaign.

In fact, if not for his rockabilly roots, the film suggests that Carter might not have become president at all. Director Mary Wharton — a long-time producer/director for PBS’s American Masters series — explores how, in the early days of his campaign, the candidate would come up with desperately needed cash simply by calling on the likes of The Marshall Tucker Band or the Allman Brothers to drop what they were doing to mount a fundraising concert.

“We’d have a concert on Saturday,” a former campaign worker recalls, “and use that money to buy advertising on Wednesday.”

As Carter himself tells Wharton, “It was the Allman Brothers who put me in the White House.”

The film makes clear that Carter was no simple opportunist; his love of music infused every aspect of his life, from the spiritual to the political. Bob Dylan marvels that on their first meeting in the White House, Carter recited many of the songwriter’s lyrics, weaving them into a personal and religious testimony.

“I realized my songs had reached into the establishment world,” Dylan tells the camera. “It made me a little uneasy.”

After his arrival in the White House, Carter filled those historic halls with music of all sorts: giants of classical, rock, gospel, and jazz all took their turns on the stage. One of the film’s most disarming passages involves trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie coaxing the prez, who famously got his start as a peanut farmer, into sort-of singing an awkward rendition of “Hot Peanuts.” Carter hosted the likes of Herbie Hancock, Diana Ross, Dolly Parton, Cher (who drank from her finger bowl) and Willie Nelson (who came to D.C. straight from incarceration after a drug bust in Jamaica).

If music enlivened Carter’s White House years, it also saw him through his darkest hours as president: At the height of the Iran hostage crisis he closed himself into his office and listened to Willie Nelson sing gospel songs.

In the end, the Carter/music connection was not enough to save his presidency. Still, there’s the sense here that it is music that continues to feed his soul — and has helped him become our greatest ex-president.

“I think music is the best proof,” Carter concludes, “that people have (at least) one thing in common, no matter where they live, no matter what language they speak.”

Featured image: Jimmy Carter with Willie Nelson, 1980 (Credit: Courtesy The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

Why President Truman Represents the Spirit of the Fourth of July

Harry Truman is not the first president who comes to mind when you think of the Fourth of July.

There is George Washington, of course, although he was off fighting the British on the day of the historical adoption and signing of The Declaration of Independence. John Adams, second president of the United States was there, in Philadelphia, a principal participant in the Second Continental Congress. And, of course, Thomas Jefferson was the principal writer of The Declaration of Independence, which was formally voted on and approved July 4, 1776.

To my surprise, almost as much as yours, I offer the name of the 33rd president of the United States, Harry S. Truman.

As I think back on it, our student press conference with him in 1946 is what the John Philip Sousa marches and the sprays of red, pink, and silver star-like fireworks in the sky celebrate each year.

It begins, in a way, with an incident at the Chicago Theatre in October 1944. I was a junior in the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University hoping to get an interview with singer Lena Horne, who was appearing there that week. The man at the stage door said I would have to ask her manager. I could wait for him to come down from the floor of dressing rooms above.

Her manager was a heavy-set man, tie loosened and shirt collar open, the stub of a cigar in one corner of his mouth. I asked. He took the cigar from his mouth, flicked it, and said, “Honey, if I let you interview her, I have to let a hundred other school editors interview her.” He did allow me to stand in the wings and watch the show, which I wrote about in a nicely featured story.

I might have done other stories for the Northwestern Daily, but my father had a heart attack, and I had to leave school. The experience of being a student trying to get an interview stayed with me, however. Especially when I got a job as a copygirl at the Chicago Daily News and saw how easy it was for reporters and columnists there.

So, a year later, when I was given an opportunity to write a column for high school and college students, I proposed that the Daily News sponsor a press club of student editors. I would set up the press conferences, the students would get experience meeting and interviewing prominent people who came to town, and their stories would appear in the school papers for other students to read. (A nice change from the usual reports on high school assembly speakers who warned against drinking alcohol lest it pickle your brain.)

And … it came to pass.

Our first interview was with the veteran movie actor Pat O’Brien. We had so few students then we met in the sitting room of his suite at the Ambassador East Hotel. We had a couple more interviews and a few more students added the second month, and I was working on a press conference with Big Band leader Tommy Dorsey when I heard President Truman would be coming to town.

The president of the United States?

It was an audacious thought.

He did fit the profile, though. A prominent person the students could not interview otherwise. So I didn’t dismiss it out of hand. But … I hesitated. Could we really, really get a press conference with the president of the United States? After several days of wondering, working up my courage, I raised the possibility with my new boss, the features editor, who upon hearing my idea said, “Honey, go out and buy yourself an ice cream cone.” After a moment, the more professional response: “You just don’t get interviews with the President of the United States.”

“Why not?” I look back with some amazement at how offended I was.

With a certain, authoritative, knew-what-he-was talking-about emphasis: “No time. Have you ever seen a presidential schedule on an out-of-town trip?”

Nineteen myself at that time and feeling something I hadn’t expected to, I said, “That’s the trouble. Everybody’s always talking about how important young people are, hope of the nation and all that, but nobody has any time for them.”

I also pointed out that was the whole purpose of the press club: to set up interviews with people the students couldn’t get otherwise. I threw in some more comments about how important young people were.

He said, as much to end it as anything hopeful — helped a bit when the phone rang — “Okay. Give me a memo on it.”

My belief in the importance of such a press conference was put on paper, and grew as I did so. Careful to marshal my facts, I worked on it for more than an hour, trying to set out the reasons. That the students who attended would represent some 250,000 students in the Greater Chicago area. Students who would read the stories in their school newspapers. And that it was important for the president to show they were important. I think I again fell back on “hope of the nation,” and “future of the country.”

After reading it over several times, I left the memo on his desk.

I learned later he sent it on to the managing editor, who sent it down to Washington to the Daily News bureau chief, who sent it over to the White House, where Charles Ross, the Press Secretary, sent it in to President Truman. The president apparently liked the idea and agreed to meet with the students.

There was to be no public announcement, though. So it was set up amidst great secrecy. Letters went out from the managing editor to the principals of the public, private, and Catholic high schools in the Greater Chicago area, and their counterparts at the junior colleges, colleges, and universities, noting the students they selected — we still only had students from some 30 or so high schools — were not to be told who they would interview. Just to save the morning of Saturday, April 6, 1946, for a special press conference.

And so it was that on the morning of Friday, April 5, students throughout Chicagoland were called to the principal’s office and told they would interview the president of the United States the following morning. They were to go that afternoon to the Chicago Daily News Building to be briefed on the press conference.

Secret Service did not want to have to worry about being sure some 100 students got through police lines around the Blackstone Hotel the next morning, so it had been agreed the students would meet at the Daily New Building and a bus would take them to the hotel. One girl, Betty Gordon of Herzl Junior College, came up to me as the briefing ended to say she was an Orthodox Jew and could not travel on Saturdays. Her parents had booked a room for her at the Congress Hotel, and she would walk the three blocks or so down to the Blackstone. Would that be okay? I said we’d tell the Secret Service man we were working with, which we did. He said he’d have his people alerted to watch for her.

It was a great relief to see her in the meeting room down the corridor from the Blackstone Hotel ballroom the next morning when I looked around. The students were dressed in their Sunday best. The girls were wearing hats and the guys were in suits and ties. And they clutched their notebooks, pencils at the ready. Outside, two M.P.’s guarded the door, one on each side. This was for our student editors. No one else.

I had a place at the head table. And waited with everyone else, until we heard a stir outside, and then President Truman appeared in the doorway. He strode down the aisle by the paneled wall, that brisk walk so familiar to Americans from newsreels and photos of his daily walks. He stopped at the table to my immediate left. White House Press Secretary Charles Ross stood next to him and addressed the students, who were still standing.

The press conference would be conducted — as we’d briefed them the day before — under White House procedures. No quoting the president directly. He didn’t say, “It’s a beautiful day.” He said that it was a beautiful day. And we only had 10 minutes, presidential schedules being as tight as the features editor had said.

Everyone sat down … except the president, who remained standing as he faced the rows of young editors. I don’t remember most of the questions, just that they were serious, and appropriate. One about the United Nations. Another about a policy. One student, aware of how critical Congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce was of the president, asked: “What do you think of women in Congress?” The president’s answer was more in his expression than his words that he thought they were fine.

The one I do remember was a boy who stood and, as many of the students did, read the question on his notepad. He had, however, added to it as he thought of other aspects … to the point that, with an occasional pause for breath, it went on and on until you didn’t know what he’d started to ask. When he stopped, all the students heads turned from him — in unison, as if they were at a tennis match — to the President. What in heaven’s name would he — could he — say?

“Obviously,” he said.

The president more than doubled the allotted time, ignoring Charles Ross’s obvious glances at his watch, until he could ignore him no more. He thanked the students and thanked me, shaking my hand as he said what good questions they’d asked. And with that, he was gone. I learned later that when he stepped outside where the regular White House press corps was waiting, he told them it was one of the stiffest press conferences he’d ever had, and they could take a few lessons from the kids.

Back inside, the students rushed up to me, excited (agog, in some cases) over my having shaken hands with the president of the United States. My right hand became a thing of some wonder. I remember one girl exclaiming, “How can you ever bear to wash it?!”

The Daily News promotion department, after a lengthy search, could find no record of a president ever having granted a group of student editors a formal press conference before. Presidents had met with students, at the White House or when traveling or campaigning, but none had ever met with them at a formal press conference. And I’ve never heard of one since.

The press conference turned out to be a milestone in my career.

But it’s what happened the next day that prompts me to share the story as part of marking the Fourth of July.

I received a call from the city desk editor on duty that Sunday afternoon saying the story was still moving on the wires; specifically, Betty Gordon’s question about the poll tax. Political pundits were taking the President’s answer to mean he wouldn’t run in 1948. Would I come in and do a follow-up story on how the kids felt after they’d had time to absorb it, the momentousness of the occasion.

That’s when I discovered that several of the students had been asked to write stories about the press conference when they came out of the meeting room. One was for the Associated Press, and Marion Bradley of Sullivan High School said she received kudos from the AP editors in New York when they received her story.

When I called student Peter Langer for my follow-up story, his mother said he wasn’t home. He and his sister had gone to the movies. She would have him call when he came home. But she did not sign off.

Instead, she said, “I would like to say something.” A hesitant pause, as I waited.

“I feel rather proud,” she said, her words coming slowly, showing a distinct accent.

I felt it through the telephone.

“I feel especially proud because we have not long been in this country. We came from Austria — Vienna — about six years ago. It is so different. You would never have had a chance to see and talk to the president over there, so I’m especially proud.”

She’d found her voice now.

“We are so proud,” she said.

“Our son … asked the president of the United States a question … and got an answer. That could never happen in our country,” she said. Awe in her voice now, “Only in America.

“Only in America.”

Featured image: U.S. Presidents George Washington (Clark Art Institute), John Adams (Wikimedia Commons), Thomas Jefferson (WhiteHouse.org) and Harry Truman (White House Historical Association)

John Quincy Adams: America’s Overachiever Gave the Presidency Pants

For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that former presidents return to private life after leaving office. Granted, they’ll take on speaking engagements, write books, paint, produce shows for Netflix, and endorse other candidates, but they don’t generally run for office again. That may be how it is now, but that’s not how John Quincy Adams did things. The first son of a president to become president himself, Adams was only the sixth person to hold the office. But that was far from the only office that he would occupy in an extremely long run at many levels of public service.

John Quincy Adams was born in 1767, the oldest of John and Abigail. When the elder Adams went to Europe on diplomatic missions during the American Revolution, the 12-year-old John Quincy accompanied him. He studied multiple languages and even worked in Russia for American statesman Francis Dana for two years. After more time spent in the Netherlands and Great Britain, Adams and his father returned to the U.S. in 1785. He attended Harvard, then law school, and saw his father become the first vice-president of the United States in 1789. Though he engaged in political writing while practicing law, he wouldn’t officially enter politics until 1794 at age 27.

1794-1796 – Ambassador to the Netherlands: Adams was an easy choice for president George Washington. He was a known quantity in the country, and his father had negotiated for Dutch assistance during the Revolution. During this period, Adams met Louisa Johnson, his future wife.

1796-1801 – Ambassador to Portugal, then Prussia: Washington switched Adams’s mission to Portugal in 1796; after the elder Adams was elected president later in the year, he appointed his son as ambassador to Prussia (the Imperial predecessor of modern Germany). When President Adams lost the next election to Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy stepped down from his post.

1802-1803 – State Senator in Massachusetts: That didn’t last long, because . . .

1803-1808 – U.S. Senator from Massachusetts: The state legislature of Massachusetts appointed Adams to the U.S. Senate. Though a Federalist when he joined the Senate, Adams began a long career of being a voice of challenge; Adams supported the Louisiana Purchase and general expansion. He quarreled with his own party after various issues involving Britain, notably impressment (that is, forcing people into service); the party rift grew such that the legislature selected his successor before his term was out, and he left the Senate entirely as its conclusion.

1809-1812 – United States Minister to Russia: After spending time teaching at Brown and Harvard and arguing a case in front of the U.S. Supreme Court (Fletcher v. Peck), Adams returned to the diplomatic life when president James Madison appointed him the first Minister to Russia. In 1811, Madison wanted to make Adams a Supreme Court Justice, but he declined, as his heart was in diplomatic work.

1812-1817 – British Delegation/Ambassador to Britain: While Adams was still in Russia, the War of 1812 broke out between the U.S. and Great Britain. Madison made Adams part of a delegation to try to end the war. A bid by Tsar Alexander to mediate between the two powers failed, so Adams left Russia by 1814. The American and British delegations met that year in Belgium to try to end the war; they delivered a treaty by Christmas Eve, 1814. The following May, Madison made Adams the official Ambassador to Britain. When James Monroe was elected president, he recalled Adams to the United States for a new job.

1817-1825 – Secretary of State: The new president had been the Secretary prior to his election, and he selected Adams to succeed him. Adams had few peers with his depth of experience and pre-existing relationships in Europe. During his tenure, Adams would help the U.S. acquire Florida from Spain, set wheels in motion that would cement Oregon’s place in the country, and helped draw down military presence for both the U.S. and Britain around the Great Lakes area. Adams and Monroe were also concerned with building relationships in Latin America and South America. As various countries emerged from European control, they set policies to limit Europe’s influence in their former colonies. That became the Monroe Doctrine, the notion that America would not interfere in inter-European affairs if Europe left the Americas alone.

1825-1829 – President of the United States: The Election of 1824 turned out to be both extremely complicated and historic. Five candidates vied for the office, including Adams’s old diplomatic (and sparring) partner Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, William Crawford, and General Andrew Jackson. No candidate received the required majority of electoral votes, which led to the contingent election codified in the Twelfth Amendment. Adams won the day, and the presidency. He also made two lasting cosmetic changes to the office; Adams dispensed with the powdered wig to show his own short hair and got rid of knee breeches in favor of trousers. Yes, John Quincy Adams brought pants to the presidency.

Adams turned out to be a one-term president, losing the election of 1828 to Jackson. The former president almost retired entirely from public life, and the heaviness on his heart only increased when his son, George Washington Adams, committed suicide the following year. However, general boredom and a growing disdain for Jackson lit a fire under Adams to do something that very few former presidents have ever done: run for office again.

Sir Anthony Hopkins played John Quincy Adams in Steven Spielbeg’s Amistad. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

1831-1848 – Representative from the State of Massachusetts: Adams ran for Congress in 1830 and won. He was 64 years old when he began his term 189 years ago this week. Adams would go on to win a remarkable nine times, serving all the way up until his death in 1848 at age 80. From his place in Congress, Adams was in the office against the backdrop of five different presidents (Jackson, Martin Van Buren, one month of William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and James K. Polk). He worked hard in support of the sciences and was the driving force of what became the Smithsonian Institute. Adams opposed the Mexican-American War and turned out to be the most prominent American voice arguing for the abolition of slavery. He returned to argue in front of the Supreme Court in the case of United States v. Amistad, speaking for four hours on behalf of slaves who revolted and seized the Spanish vessel; Adams won the case, which ended with Supreme Court granting the slaves freedom and returning them home.

While casting a vote in Congress on February 21, 1848, Adams suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on the floor of the House. He died two days later in the Speaker’s Room of the Capitol Building with Louisa, his wife of more than 51 years, at his side. It’s no small irony, and perhaps entirely appropriate, that he literally took his last breaths inside one of the institutions to which he’d devoted his life. His last recorded words were, “This is the last of earth. I am content.”

Today, Adams is largely remembered in a general sense for simply being the first president that was the son of a president. That does a critical disservice to his instrumental role in any number of historic endeavors. Widely considered one of the more intelligent presidents and certainly an admirable diplomat, it was Adams’s broad range of skill and ability that helped him continually resurface in public life. Maybe it’s up to modern America to take the time to give Adams a new kind of return, one to more public awareness of his crucial role in our common history.

Featured image: John Quincy Adams’s tomb in Quincy, MA.(Joseph Sohm / Shutterstock)

Killer in the White House

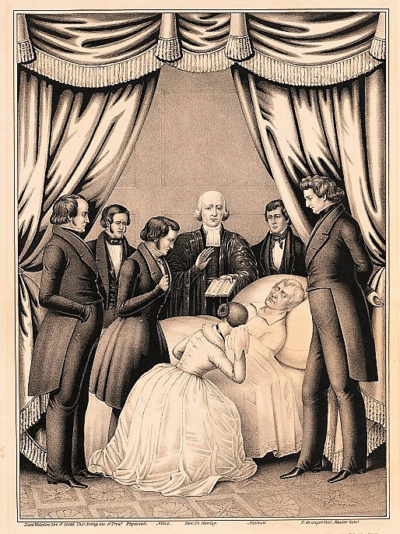

It’s February 20, 1862. The nation is torn by Civil War. Elements of the Union Army camp along the Potomac River; men and horses alike are struggling with the bitter cold. Yards away, inside the home of the president, a different struggle draws to an end. There’s a killer in the White House, and before the night is over, what that killer does will irrevocably shatter the Lincoln family.

Young Willie Lincoln is his father’s favorite, if he would admit such a thing. He’s also his mother’s favorite. His older brother Robert is away at Harvard, and his younger brother Eddie died at age three. Eight-year-old Tad Lincoln is the “notorious” hellion; the White House is his jungle gym and he’s known for an unrestrained free spirit. But Willie, Willie is like his father. Even at 11, he takes the role of the serious older brother; family friends describe him as bright and lovable. Willie loves to read and write. He’s one of the bright points for his father in a dark time in history. But on the evening of February 20, Willie Lincoln lies in a bed on the second floor of the White House, with his mother and father at his side, gasping for air and clinging to life. It would be on this evening, in this room, where Willie Lincoln succumbed to a silent killer.

Initially, Mary Lincoln blamed his death, and that of Eddie, on the family’s political ambitions. In a letter to a friend she wrote, “Our heavenly Father seems fit to visit us at such times, for our worldliness.” What Mary Lincoln did not know is that Willie’s death was not the poisoned fruit of political ambition, but more likely, it was caused by the same disease that stole the life of three former presidents and countless other Washington, D.C. residents in years past.

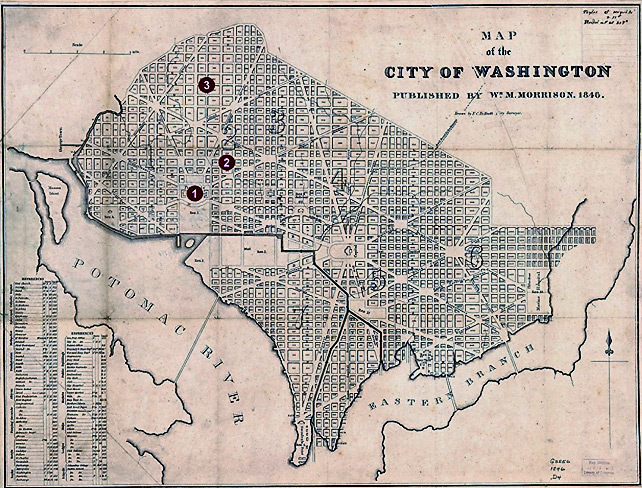

To understand what may have claimed the lives of these victims we have to take a look at Washington, D.C. at the turn of the 19th century. The new federal city was supposed to be a shining beacon of democracy and freedom; instead, it was an overgrown swamp with primitive roads and almost no infrastructure. John Adams became the first president to move into the White House in November of 1800. The would-be mansion was damp, poorly ventilated, and a far cry from what tourists see today on Pennsylvania Avenue. Abigail Adams famously lamented about having to hang the family laundry to dry in the East Room.

The rest of Washington, D.C. was not much better off. The small, makeshift city was struggling with some of the more basic municipal maintenance concepts that Americans take for granted today. One of those non-existent amenities was solid waste processing. The lack of a sewer system caused early residents to leave their so-called “night soil” in the streets. It would then be collected and deposited in a sparsely populated section of the near north side of the city.

This night soil depository was believed to be in the vicinity of the modern intersection of 15th Street and R Street. Today, the quiet residential neighborhood is home to a hostel and a Presbyterian church. And while its residents today may not know, the effects of what happened in this neighborhood may have had long lasting consequences on the history of the United States.

In the early years, water was carried in buckets to the White House by servants and stored in two wells inside breezeways. Piping running water into the White House was first proposed during the James Madison administration, but before this work could be started, the White House was burned to ashes by the British in 1814 during the War of 1812. In 1829, the Committee on Public Buildings again proposed piping water into the White House. The purpose was not for bathrooms, toilets, or kitchen use, but instead for fire protection. With the 1814 torching still fresh in their memory, officials were nervous about the possibility of another fire destroying the president’s house. Up to this point, the only fire protection the White House had was a fire engine that was purchased by President James Monroe and was parked in the carriage house behind the White House. Ultimately, instead of appropriating the funds to install the pipes for running water, the committee spent the money on repairing the north portico of the White House.

Besides gaining funding for the project, another issue was the question of how to get the water to the White House. With the lack of ground water beneath the house, the Committee on Public Buildings set out to find a suitable source of water nearby. In a letter to President Thomas Jefferson on May 27, 1807, surveyor Nicholas King proposed pumping water from a spring just six blocks north of the White House. Located at the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and 16th Street West (the current location of the General Winfield Scott statue), the spring sat at an elevation of about nine feet above the White House. King suggested delivering the water to the White House from the spring using a series of pipes.

But this proposed site and plan was never used. Instead, the Committee on Public Buildings purchased a spring in Franklin Square in 1831. The site was only four blocks northeast of the White House and was closer than the site that King suggested in 1807. Ground was broken on the site in 1833. Engineer Robert Leckie was put in charge of the project. Leckie had extensive experience in leveling streets and building water lines in Georgetown and Washington, D.C.

Leckie used iron pipes to run the water from the spring in Franklin Square to three small reservoirs located in the Treasury building, the State Department, and the White House. Since the spring was at a higher elevation than the White House, gravity did most of the work. Leckie completed this system at the end of May, 1833.

President Andrew Jackson was the first resident in the White House to take advantage of this new running water. No concern was given to the pipes, the water, its source, or even the bacteria-filled night soil depository that was located uphill, less than a mile away from the spring.

Complicating matters in Washington, D.C. was the city canal. As if the contaminated water from the Franklin Square spring weren’t enough of a health risk, the Washington, D.C. canal was a danger all on its own.

The canal ran along what is now Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C. It was an original feature of the city, designed to connect the Anacostia River with Tiber Creek. Since the canal ran through the heart of Washington, D.C. and bordered the National Mall, it was subject to a lot of misuse. Soon after its opening in 1815, it quickly became nothing more than an open sewer, with reports of citizens dumping raw waste and animal carcasses. Since it was not covered, many drunken patrons, fresh from a visit to the local pub, found themselves immersed in its filthy waters. A foul stench emanated from it, exacerbated by the long and hot Washington, D.C. summers.

The canal ran only one block south of the White House. It is easy to see how bacteria and disease could find its way onto the White House grounds from such a lengthy, uncovered channel.

The threat from the canal was compounded by the Potomac River. Visitors to Washington, D.C. today would have to walk over two miles from the White House to reach the banks of the river, but up until the late 19th century, the Potomac River stretched across the National Mall and reached the city canal. It was not until the completion of the Washington Monument that officials began to dredge the land around the mall and fill it in with earth, pushing the river back to its present-day boundaries. The city canal was finally covered in 1872. The local drunks could now freely walk about without fear of falling to a slimy fate.

But recent research shows that all of these factors presented a larger danger than anyone at that time would realize.

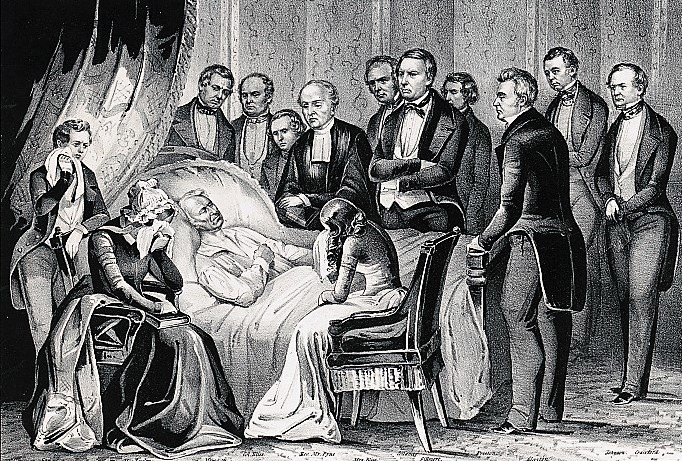

In March of 1841, President William Henry Harrison delivered his infamous inaugural address, a two-hour speech made in cold and rainy conditions that many at the time believed caused his untimely death the following month. But over a century-and-a-half later, science points to a different source of the president’s demise.

In a 2014 study for Oxford Academic, Jane McHugh and Philip Mackowiak theorize that Harrison was actually killed by the running water in the White House. Their study first takes a look at the initial diagnosis from Harrison’s doctor, Thomas Miller; Miller claimed that the president’s eventual cause of death was pneumonia. However, the symptoms Harrison displayed during the time he lay on his deathbed in the White House were more consistent with that of enteric fever and a gastrointestinal infection, which could have been brought on by a parasite or bacteria introduced through contaminated water in the White House.

Harrison initially complained to Dr. Miller of anxiety and fatigue three weeks after his inauguration. These ailments quickly gave way to nausea, constipation, and a rising body temperature. These symptoms were treated with a steady regimen of mustard plasters, laxatives, laudanum, and enemas. Obviously, Dr. Miller was treating President Harrison’s symptoms, and not the actual cause of his ailments.

In their study, McHugh and Mackowiak theorize that since Harrison’s “pulmonary symptoms were not as severe as his gastrointestinal distress,” it is more likely “that he died of a gastrointestinal infection.” They go on to explore the possibilities of this infection being the product of the bacteria S. paratyphi. President Harrison’s infrequent, and then frequent (thanks to the many laxatives he was given) stool samples strongly resembled those of typhoid patients (in fact, a number of sources attribute Harrison’s death to typhoid, treating it as a settled question). The Oxford Academic study concludes, “There is ample reason to conclude that Harrison’s move into the White House placed him at particular risk of contracting enteric fever.”

Rather than the inclement weather, the water that Harrison drank, bathed in, and cleaned with was more than likely the cause of his demise.

As Harrison lay in his deathbed on the evening of April 3, 1841, he uttered his final words; “Sir, I wish you to understand the principles of government; I wish them carried out, I ask nothing more.” Over the next four hours, his pulse would slowly drop, until he stopped breathing at 12:30 the next morning.

Only eight years later, an eerily similar situation was playing out in Nashville, Tennessee. On June 15, 1849, James K. Polk lay in a bed, his body rocked by diarrhea, vomiting, and severe dehydration. Only three months prior, Polk was finishing up his only term as President of the United States. But now, he was consumed by cholera morbus; a common gastrointestinal illness.

Polk spent most of his life fighting various illnesses. From kidney stones to gallstone removal, he was no stranger to fighting back from ill health. But this bout of cholera was too much for the 53-year-old.

While it’s not possible to definitively link the contaminated water in the White House to the death of a former occupant, the similarity in the symptoms between Polk and Harrison are striking. The gastrointestinal issues that haunted Harrison in his final days reappear in Polk, shortly after Polk left the White House. These symptoms are most commonly the result of the introduction of a waterborne bacterial parasite, like S. paratyphi. In the four years that separated the death of Harrison and the inauguration of Polk, little improvement was made on the White House water system.

While Polk made it out of the White House before he succumbed, his immediate successor did not. Just a year-and-a-half after taking office, President Zachary Taylor found himself in an ominous position.

It was commonly accepted that President Taylor became ill after consuming too much iced milk and cherries on July 4, 1850. But in a 2003 biography of Taylor, The Life of Major General Zachary Taylor: Twelfth President of the United States, author Henry Montgomery reveals that Taylor also “partook freely of water” during his Independence Day binge eating session. Within an hour of eating the cherries and drinking large amounts of iced milk and water, Taylor began to complain of cramping. These cramps gave way to vomiting, diarrhea, and other symptoms that are associated with water-borne illnesses, including cholera and typhoid.

Five days later, after fits of violent diarrhea and vomiting, it was time for Taylor to take his place in history by uttering his last words: “I have endeavored to do my duty, I am prepared to die. My only regret is in leaving behind me the friends I love.” Had the water in the White House claimed its third president in six years?

Back at the White House, little progress was made on the sourcing and sanitization of running water. In 1860, President James Buchanan ordered running river water to be pumped to the second floor of the White House for bathing. Luckily for Buchanan, that work was not completed until his successor and his family moved into the White House.

Young Willie Lincoln was strong, exuberant, and full of life. Unfortunately, he, like three presidents before him, was likely not strong enough to overcome decades of mismanagement with the White House plumbing system. At the time he fell ill, water from the tainted spring in Franklin Square was still being used in the White House. The open and festering city canal was still running just one block south of his home. Willie and his younger brother would often climb to the roof of the White House and look out on Union soldiers who were camped along the Potomac River, just a few blocks away. Little did Willie know that those soldiers were often relieving themselves and dumping discarded animal carcasses in that river. That very same water was being piped upstairs to the second floor of the White House, and young Willie was likely bathing in it frequently. He was unaware of the microscopic bacteria that was entering his body. As with the deaths of Presidents William Henry Harrison, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor, this was likely his silent killer.

Rockwell Video Minute: Portraits of Presidents

Norman Rockwell spent his share of time in Washington, D.C. painting presidents and presidential candidates. He said, “I am no politician and certainly no statesman. But I have painted thousands of people and I should by now be a judge of what their faces say about what they are.”

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series at saturdayeveningpost.com/category/rockwell-video-minute/.

Surprising Presidential Firsts

See all of The Saturday Evening Post videos.

News of the Week: Gross Toys, Confusing Tennis Balls, and the Original Twizzle

This Is Snot Your Father’s Toy Fair

Here’s a memory: Creepy Crawlers.

They were bugs you made in the oven. You put the goop into tray molds and then bake it. Voilà! Wiggly bugs to freak out your mom and older sisters. I thought of those while reading about this week’s New York Toy Fair and some of the new outlandish toys that made their debut.

Toys are now a lot more bodily-function-oriented than when you and I were kids. They’ve come a long way since Creepy Crawlers, Wacky Packages, and Whoopee Cushions. For example, there’s Sticky the Poo from Hog Wild, which is exactly what you think it is, and sticks to your walls and appliances. Hasbro has a game called Don’t Step In It, where blindfolded players have to avoid … actually, you can probably guess the object of the game, so I’m not going to finish that sentence.

Not to be outdone, KD Games has a new game called Snot It, where you put on what at first looks like an ordinary old-fashioned pair of glasses and nose, but actually has something hanging from the nose that you use to pick up game pieces. I’ve tried to explain that as delicately as I can, but you have to see it for yourself.

I hope kids still play Monopoly too.

What Color Is a Tennis Ball?

It’s yellow. Hey, we settled that quickly!

Or is it green? That’s the discussion people are having online as tennis season gets into full swing. A Twitter user put up a poll this week asking followers what color the ball is. 52 percent of respondents say it’s green, while 42 percent say yellow.

Yes, this is turning into another “Is the dress black and blue or white and gold?” debate.

Six percent of the respondents said the color was “other,” which makes me wonder what this “other” color could be.

And the Worst President Is…

Speaking of polls, the American Political Science Association released one this week in which 170 scholars were asked for their list of the best and worst U.S. presidents. The ones you imagine would be near the top are indeed at the top (Lincoln, Washington, both Roosevelts, Jefferson, Truman), and the bottom-dwellers are the ones you’d expect to see there too (Pierce, Harrison, and Buchanan). I think it’s rather unfair for Harrison to be listed as one of the worst. The poor guy died of pneumonia just a month after being sworn in (he refused to wear a jacket on the day of the inauguration because he wanted to look stoic), so maybe there should be an asterisk next to his name.

Our current president came in dead last, though if we’re to be fair, the others are being judged on full four- or eight-year terms, when Trump has only been in office for a little over a year.

But a lot of people have always chosen Andrew Johnson, who came in fifth from the bottom on the poll, as the worst of all time. CBS Sunday Morning correspondent Mo Rocca did a segment on Johnson and the town that is still proud of him.

The Book of the Month Club Is Still Around

Are books here to stay? Random House co-founder and What’s My Line? panelist Bennett Cerf wrote a piece for the Post back in 1958, when television was starting to rule our minds, answering that very question. Post Archive Director Jeff Nilsson asked the same question in 2013, and with the popularity of eBooks and various reading devices rising, it’s a question worth talking about. If my spending habits are any indication, books are never going to go away, and in fact, even if a book is digital and not print, it’s still a “book” (print vs. digital is a different debate).

But as someone who buys a lot of books, I was happy to come across the website for the Book of the Month Club this week. Honestly, I didn’t know they were still around. Looks like they’ve updated things for the age of the internet. The club is a great way to not only encourage reading, but also to find some books you might not find or select for yourself.

Let’s Twizzle!

“Twizzle” sounds like something Snoop Dogg would say, but it’s actually the name of an ice skating move currently being performed and talked about at the Winter Olympics in South Korea. But fans of The Dick Van Dyke Show know what the real dance move is (and I apologize in advance because this song is going to be in your head for the rest of the day):

RIP Billy Graham

The Reverend Billy Graham was known as “America’s pastor.” Besides preaching to millions of people around the world for several decades, he was a counselor to every U.S. president since Harry Truman. He died Wednesday at the age of 99.

A profile of Graham, written by Harold H. Martin, appeared in the April 13, 1963, issue of the Post.

The Best and the Worst

The best: This piece by Tim Wu at The New York Times on the tyranny of convenience. This issue has worried me for the past decade or so, with how we often give up quality just because something is quicker or more convenient.

The worst of the week just might be Fergie’s jazzy, sexy rendition of the National Anthem at the NBA All-Star Game. It’s not often you see players and fans openly laughing at the singer of the national anthem. Is it the worst of all time, though? It’s certainly the most, well, different version of the song that we’ve heard at a national sporting event, though one could argue that Roseanne Barr’s 1990 performance is even worse. At least Roseanne was trying to be funny. And hey, she didn’t have to write the lyrics on her hand.

Quote of the Week

“We really want girls to be cookie entrepreneurs, to find new and creative ways to reach customers.”

—AnneMarie Harper, spokeswoman for the Colorado Girl Scouts, after one of the girls sold 300 boxes of cookies outside of a marijuana shop.

This Week in History

Huckleberry Finn Published (February 18, 1885)

In the September 22, 1900, issue of the Post, reporter Homer Bassford went to Hannibal, Missouri, to speak with the boyhood friends of writer Mark Twain (aka Samuel Clemens).

First Woolworth Opens (February 22, 1878)

One of my fondest memories of childhood was going downtown to Woolworth’s and shopping with my mom. I can still remember where everything was, including the staircase that led down to the toy department. The building is still there. The awning is gone, and it’s now occupied by several small businesses, but you can make out what it once was.

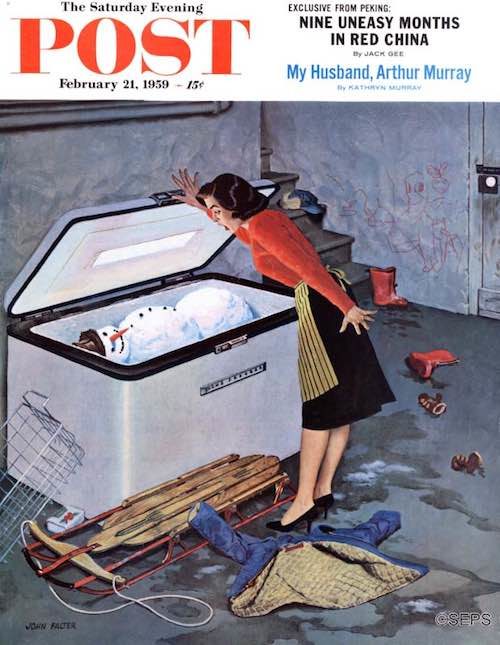

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Frosty in the Freezer (February 21, 1959)

John Falter

February 21, 1959

This cover by John Falter has to be one of the oddest the Post has featured. It has always seemed a little like the start of a horror movie to me. The mom finds a snowman in the basement freezer and she assumes it’s dead, but the cold has kept it alive and it attacks her. The movie’s tagline: He’ll be back again some day.

Today Is National Banana Bread Day

I don’t know why people insist on putting walnuts in banana bread, ruining what is otherwise a terrific dessert and/or snack, but here’s Curtis Stone’s recipe, which seems to go out of its way to mention that it features “lots of toasted walnuts,” just to irritate me.

Here’s a recipe that doesn’t have any walnuts at all but does include chocolate chips, and this recipe uses, well, just bananas.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

National Sword Swallower’s Day (February 24)

It’s great that sword swallowers have a day all to themselves, but I feel the need to say “don’t try this at home.”

National Pig Day (March 1)

How does one celebrate this day without actually eating something made from a pig, which would be a rather cynical thing to do? Maybe by reading this story about Pigcasso, the pig who paints. Right now she only gets food rewards for her work, but I bet they could sell one of the paintings for a lot of money and really bring home the bacon.

(Sorry about that.)