Why Is Our Country So Divided (and What Can We Do About It)?

The name of our nation claims we are united, but one could compile a history of America just by chronicling our civil conflicts. Starting with the clash over the independence movement, Americans have been bitterly divided over tradition, faith, morals, and the rights of people of color, women, the poor, immigrants, and other groups. And, of course, we are divided between political parties.

Today, there’s a deep gulf in American opinion, which seems to be growing wider and deeper.Back in 1994, a Pew Research Poll reported that the partisan split over racial discrimination, immigration, and international relations was 15 percent. By 2017, it was 36 percent.

Spencer Critchley, author of Patriots of Two Nations: Why Trump Was Inevitable and What Happens Next, says that behind many of our arguments lie polarized views of the world that go back to our earliest days.

Critchley explains that on one side are the followers of Enlightenment, who believe in science, reason, and the rule of law. It was enlightenment thinkers who framed our government and wrote our Constitution. Today’s followers of the enlightenment believe in a “civic nation,” founded on a social contract between the individual and the state. The citizen exchanges a measure of personal liberty for membership in a mutually supportive society.

On the other side are followers of the Counter-Enlightenment, who believe a focus on reason is too constraining. It doesn’t account for culture, art, tradition, spirituality — the elements that bring richness to life. This group believes in an “ethnic nation,” which is rooted in their race and culture. While this focus can appeal to bigots, counter-enlightenment people are not necessarily racist. In an interview with the Post, he said,“Many thoughtful people come from the counter-enlightenment world view.”

The gap between the two world views is so great that Critchley, a former campaign advisor to Barack Obama, says that it has created alienation and suspicion, helped on by politicians and the media playing on resentments. “Much of the division has been exaggerated,” he says. “A lot of money can be made by making people angry and afraid.”

Yet there are a considerable number of Americans who have embraced the extremes of ideology. At the far extremes of counter-enlightenment are white supremacists. At the other extreme are people who Critchley says believe in “identity policing, endless litigating, political correctness, and punishing people for not being ‘woke’ enough.”

Critchley, who considers himself part of the enlightenment crowd, is aware of how easy it is to dismiss the opposing points of view. He says, “We live lives of high rationalism most of the time. We think in terms of facts, logic, productivity. We tend to believe facts and logic explain everything.”

The two groups’ attitudes toward culture is significant, he adds. “Enlightenment people can become disconnected from any particular culture. This is part of what’s behind the ‘globalist’ charge. Sometimes that refers to the global financial elite, and sometimes it’s veiled antisemitism, but it can also point to this sense of cultural emptiness.” Critchley says that globalism is a concept that disconnects people from the symbols and traditions that shape their lives. Critchley compares it to the campaign to teach Esperanto, “the international language.” He wonders at “the idea that anyone would want to speak a language rooted in no culture at all.”

What is true in language is also true of history, art, and human psychology. Counter-Enlightenment people “would argue that people are inherently subjective and tied to a particular location.” Culture is crucial.

Says Critchley, “The Democratic party — I’ve seen it up close — is sometimes stuck in a science-driven world. They’re really good at using science and coming up with solutions.” But they can be oblivious to culture.

“A lot of liberals would be surprised that while more than 90 percent of Blacks consider themselves Democrats, only about a quarter would define themselves as liberal.” Critchley says that they need to recognize “there are many cultures alive in the Black community.”

The current level of social friction threatens to get out of hand. But the situation can’t be blamed on a polarizing president and the general tone of today’s politics, Critchley maintains. The ideological division is far older and runs far deeper, and will still be with us after this administration has gone.

Sooner or later, we must make the effort to reunite. The solution, Critchley says, is like dieting: “it’s simple but it’s hard.”

When talking with someone with a different perspective, he advises, “stop trying to make sense for a while, stop trying to correct them. Practice some awareness, compassion. And find some shared values.”

It will probably take some digging and the results may be surprising. “We must learn to respond to people in a more intuitive way,” Critchley says. “We must build trust. Connect first, debate later.”

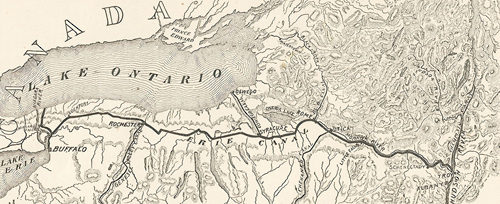

Featured image: Map from the cover of Patriots of Two Nations: Why Trump Was Inevitable and What Happens Next by Spencer Critchley (McDavid Media, ©Spencer Critchley. All rights reserved.)

The Best Road Trips in Every State

We scoured the nation for the best driving excursions in every state. Many showcase stunning fall foliage backdrops. Others present unique and spectacular geography. In some cases, we bypassed the best-known byways to feature hidden gems. Oh, we surely missed some — there are just too many to choose from. (Let us know your favorites in the comments below..) We hope to inspire you to venture out and explore this beautiful country we call America. Happy motoring!

Alabama

Wrapping around Mobile Bay on Alabama’s southern tip, the 130-mile Coastal Connection Scenic Byway runs alongside pristine, powder-white Gulf beaches, shorebird sanctuaries, pecan and produce farms, and historic Fort Gaines and Fort Morgan.

Alaska

Dream of driving from Fairbanks to the Arctic Circle? Then gas up and prepare to not see another human soul for hours, just lots of wildlife, including migrating caribou, Dall sheep, musk oxen, and arctic foxes. While spellbinding, the rugged 415-mile mountain-pass Dalton Highway is largely void of civilization and creature comforts.

Arizona

A favorite of motorcyclists and sports car enthusiasts, the harrowing 123-mile Coronado Trail, aka Devil’s Highway, ascends, narrows, dips, and twists through more than 400 switchbacks as it climbs from high desert floor to 9,000-foot alpine forest.

Arkansas

Arkansas’s 363-mile section of the multi-state Great River Road runs alongside the Mississippi River through its Delta region, brimming with ancient Native American and Civil War sites, steamboats, and Mark Twain’s boyhood haunts.

California

U.S. Route 395, “El Camino Sierra,” stretches from Mexico to Canada, and the California section packs in some of its most diverse landscapes: 14,000-foot peaks, tufa formations, ancient volcanos, ghost towns, and a bristlecone pine forest.

Also check out: The Gold Rush Highway journeys through California’s gold rush era in the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas.

Colorado

Drivers cross the Continental Divide twice while traversing the Top of the Rockies Scenic Byway’s 82 miles from Aspen to Copper Mountain. The road seldom drops below 9,000 feet while passing through three national forests — Pike, Arapaho, and White River — abounding with bighorn sheep, red-tail fox, and mountain goats.

Connecticut

Rolling hills, covered bridges, historic taverns, charming villages … the vast array of Litchfield Hills Loop’s scenic routes will have you wondering if you’ve been dropped in an Andrew Wyeth canvas.

Also check out: Trailing the coastline, the 105-mile Connecticut Coast Scenic Highway between Stonington and Greenwich features salt marshes, wide beaches, and some of the East Coast’s oldest towns.

Delaware

Tranquil, two-lane Bayshore Byway parallels the Delaware Bay and migratory flyways between New Castle and Lewes. Antique-filled towns give way to corn and soybean farms, wildlife refuges, and marshlands.

Florida

The southernmost leg of Route 1 spans 165 miles over scenic bridges from Miami to Key West, showcasing coral islets, reedy wetlands, and unobstructed sunsets over the aquamarine sea. Watch for white herons, roseate spoonbills, pelicans, and dolphins.

Georgia

Three-state Russell Brasstown Scenic Byway travels 40 miles through Georgia’s mountain country, crisscrossing Brasstown Bald (Georgia’s highest peak), granite canyons, and the Chattahoochee River.

Hawaii

Just 11.2 miles long, the Big Island’s Mauna Loa Road traverses lava fields and koa forests while climbing majestic Mauna Loa for panoramic views of Kilauea volcano.

Also check out: Famed for its 620 curves and 59 bridges, Maui’s Hana Highway abounds with fragrant South Pacific foliage (think rainforests, cascading waterfalls, and multi-hued beaches).

Idaho

The Ponderosa Pine Scenic Byway’s 131 wooded miles wend from Boise to Sun Valley, past old gold mines, Western towns, and national forests, including the massive Frank Church–River of No Return Wilderness.

Illinois

Nicknamed a “living museum,” 150-mile Illinois River Road Scenic Byway embodies more than 100 nature-based, historic, and cultural sights, including Lewistown’s Dickson Mounds Museum, which interprets the ecology of the Illinois River.

Indiana

The Indiana track of America’s first paved transcontinental route, the Lincoln Highway, includes a sundry of historic sites (some commemorating Abraham Lincoln) a circa-1889 synagogue, and lodgings from the early days of road-tripping.

Iowa

Travel the 82-mile Covered Bridges Scenic Byway across Madison County and see the five famous bridges. Also drive by the birthplace and museum of legendary actor John Wayne and the stunning Iowa Quilt Museum, both in Winterset.

Kansas

Western Vistas Historic Byway, a 102-mile, one-time pioneer and cowboy trail (trod by the likes of “Wild Bill” Hickok), encompasses extraordinary landscapes, 70-foot spire Niobrara Chalk formations, dinosaur fossils, and limestone-ledged buttes amid roaming buffalo and prairie dogs.

Kentucky

Trekked by Daniel Boone, Civil War soldiers, and European explorers, the 92-mile Wilderness Road Heritage Highway features Cumberland Gap National Park, mountain music venue Renfro Valley, and Kentucky’s crafts capital, Berea.

Louisiana

Bayou Teche Byway loops 125 miles through lush bayous, Acadian cultural districts, and the country’s largest wetland, the million-acre Atchafalaya Swamp Basin.

Maine

The 125-mile Bold Coast Scenic Byway winds through Downeast Maine’s craggy seashore, foggy coastal forests, blueberry barrens, and historic towns Milbridge and Eastport, filled with maritime heritage.

Also check out: Old Canada Road National Scenic Byway, a mountain-hugging trail tracing a logging-era U.S.–Quebec trade route.

Maryland

Three hundred years of history, marked in significant mileposts, tollhouses, taverns, and stone arch bridges, line the Historic National Road’s 170 miles spanning Baltimore to Maryland’s western border.

Massachusetts

Mohawk Scenic Byway began as a Native American trade route. Centuries later, Benedict Arnold marched his army here. Today, its 69 miles offer centuries-old churches, mountain passes, pristine rivers, and quaint towns.

Michigan

U.S. Route 23 stretches from Florida to northern Michigan. Avoid all of it … except its final 200 miles along Lake Huron’s Sunrise Coast. The panoramic Huron Shores Heritage Route snakes along hardwood forests, waterfalls, sand dunes, and freshwater beaches.

Minnesota

Road trippers pass by four of Eastern Minnesota’s state parks, basalt rock cliffs, steep gorges, and 19th-century towns, including lovely Stillwater, following the 124 rolling miles of the St. Croix Scenic Byway.

Also check out: Minnesota River Valley National Scenic Byway, 287 miles of prairies, woodlands, and Dakota heritage.

Mississippi

Traversing three states, the Natchez Trace was once an east-west passage for Native Americans, slave traders, and campaigning presidents. Mississippi’s 308 miles include a Plaquemine-culture ceremonial site, the antebellum Windsor Ruins, and Elvis’s birthplace.

Missouri

Just 27 miles long, Glade Top Trail in the Ozarks is the Show Me State’s only National Forest Scenic Byway. Largely unchanged since its construction by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, its many panoramic “pull-outs” showcase limestone glades, tall-grass prairies, and eastern red cedars in the Mark Twain National Forest.

Montana

The All-American Scenic Byway Beartooth Highway abuts a plethora of national forests, climbs high alpine plateaus, overlooks glacial lakes, and crosses the 45th parallel — the halfway point between the North Pole and Equator.

Also check out: Seeley-Swan Scenic Drive spans 90 miles between the Bob Marshall Wilderness and Mission Mountains.

Nebraska

Outlaw Trail Scenic Byway’s 231 miles of rough, rambling topography made it a prime hideout for Old West bandits like the James Gang and Doc Middleton. Sights include Smith Falls (Nebraska’s tallest), Monowi (a one-resident town), and authentic cowboy saloons.

Nevada

The landscape fluctuates between high and low desert microclimates along 355-mile Great Basin Highway. Don’t miss the Miller Point and Mathers Overlooks, Lehman Caves, and the 19th-century Ward Charcoal Ovens.

New Hampshire

The Kancamagus Scenic Byway’s 34.5 alpine miles through the White Mountains deliver monumental panoramic overlooks (especially the 2,860-foot Kancamagus Pass), dramatic bluffs, lush forests, and Sabbaday Falls.

New Jersey

Bucolic 89-mile CR-519 feels more New England than central Jersey. This country lane twists through picturesque woodlands with idyllic rivers, wholesome farmsteads, and tiny towns. Fittingly, it’s nicknamed The Land of Make Believe Highway, after one of its many roadside attractions.

New York

We’ll bet no other 30-mile drive ever felt as thrilling. Interconnected by a series of stunning mountain passes, the Adirondacks’ High Peaks Scenic Byway ascends through verdant forests and past crystal-clear waterways, offering views of more than 40 peaks that soar over 4,000 feet.

New Mexico

Trail of the Mountain Spirits Scenic Byway weaves for around 100 miles through high desert forests and wilderness regions where Wild West explorers once roamed. Interspersed within jaw-dropping vistas are the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, desert towns, and the Continental Divide.

North Carolina

Sandwiched between the Atlantic Ocean and Pamlico Sound, Outer Banks National Scenic Byway breezes through 138 miles of driving (plus another 25 miles by ferry) alongside salt-air beaches, sea turtles splashing around barrier islands, quiet coastal villages, and wildlife refuges.

Also check out: Famous Blue Ridge Parkway, America’s longest linear park, runs 469 miles through the breathtaking Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina and Virginia.

North Dakota

Extending 64 miles from the Killdeer Mountains to the Badlands, Killdeer Mountain Four Bears Scenic Byway’s hilly landscape provides visual respite from North Dakota’s flat, barren terrain. The drive is a cultural tour of the region’s history, featuring the 1864 Killdeer Mountain Battlefield and the reservations of native Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes.

Ohio

The 26.4-mile Hocking Hills Scenic Byway offers so many Instagram-worthy vistas and must-see historic sites, driving it could take the whole day. The road winds around Hocking Hills State Park’s towering Black Hand sandstone cliffs, carved gorges, recessed caves, and plunging waterfalls.

Oklahoma

Nineteenth-century Texas ranchers drove millions of cattle across the Chisholm Trail to Kansas for beef distribution in the north. The Oklahoma portion (now US-81) is exquisitely rural, with sightsee stops dedicated to cowboy and outlaw history.

Oregon

The Pacific Coast Scenic Byway follows Oregon’s 363-mile coastline. Public beach access is protected by state law, ensuring opportunities for up-close views of soaring cliffs, marine caves, dunes, splashing sea lions, and naturally formed landmarks.

Also check out: Circling from Baker City to Le Grande, Hells Canyon Scenic Byway snakes above America’s deepest (7,993 feet) canyon.

Pennsylvania

The 265-mile Scranton-to-Warren portion of Scenic Route 6 is at its most impressive in the Endless Mountains, Pennsylvania Wilds (home to Pennsylvania’s Grand Canyon), and the hardwoods and hemlock of the Allegheny National Forest.

Rhode Island

Covering just 13 miles in the nation’s smallest state, RI-77 offers waterfront Sakonnet Peninsula vistas and alluring places to explore: Nonquit and Nannaquaket Ponds, the Emilie Ruecker Wildlife Refuge, and historic towns Tiverton Four Corners and Little Compton.

South Carolina

We love 118-mile Cherokee Foothills Scenic Highway’s picturesque path through the Blue Ridge Mountain’s Piedmont region, featuring glistening green forests with cascading waterfalls, jagged granite cliffs, and the postcard-perfect mountain town Walhalla.

South Dakota

The 68-mile Peter Norbeck National Scenic Byway drives like an amusement park ride, tackling hairpin curves, spiraling bridges, plunging tunnels, and granite pinnacles. Mt. Rushmore and Cathedral Spires are added bonuses.

Tennessee

The Cherohala Skyway gives you mile-high views of the Cherokee and Nantahala National Forests as it zigzags past freshwater mountain lakes and waterfalls, crimson and gold vistas, and apricot fall foliage.

Texas

The longest highway in Texas, the 542-mile, two-lane Highway 16 travels through dusty ranchlands, red rock hills, cowboy towns, and the Hill Country’s “Swiss Alps of Texas.”

Utah

Traversing the Grand Staircase-Escalante, Henry Mountains, and Capital Reef Natural Park, the otherworldly geology along 123-mile Scenic Byway 12 doesn’t disappoint with its random arches, “hoodoo” rock formations, and deep-slot canyons.

Vermont

The 51-mile Northeast Kingdom Scenic Byway showcases quintessential Vermont backcountry: hilly farm towns, colorful mountains, covered bridges, and shimmering lakes.

Also check out: The Crossroad of Vermont Byway with panoramic views of and from the Green Mountains.

Virginia

Skip Skyline Drive, swarming with bumper-to-bumper scenery seekers. Southbound from Winchester to Roanoke, the Wilderness Road meanders through the Shenandoah Valley’s historic towns and natural wonders: vertiginous sandstone cliffs, gushing waterfalls, and majestic mountains.

Washington

The 440-mile Cascade Loop encompasses three scenic byways, touring through Washington’s diverse array of ecosystems: Puget Sound islands, open desert, lush forest, craggy alpine peaks, sagebrush lowlands, and cityscapes.

West Virginia

The 180-mile Midland Trail National Scenic Byway offers mountain landscapes; plummeting waterfalls; purveyors of authentic Appalachian craft food, drink, and art; mountain-music venues; and adventure destinations for rafting, spelunking, and fly fishing.

Wisconsin

The 100-mile Lower Wisconsin River Road through the Driftless Area was Wisconsin’s first designated scenic byway. Following the Wisconsin River, it winds around rocky bluffs, through mysterious bottomlands, and into quaint river towns.

Wyoming

Encompassing 162 miles of steep mountain passes and verdant forests, through Grand Tetons National Park and famous Jackson Hole, Parks Centennial Scenic Byway is cited as one of the finest drives in the Rockies.

Stephanie Citron (stephaniecitron.com) is a contributing editor for The Saturday Evening Post.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Maciej Bledowski / Shutterstock

The War That Made Us Who We Are

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the March/April 2011 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

The war fought by Americans against Americans on American soil, for four excruciating years is still the deadliest war in American history. More than 600,000 fighting men were killed, some of them brothers in arms against brothers, and uncounted civilians died. It was a war over nothing less than whether to preserve or end the United States of America.

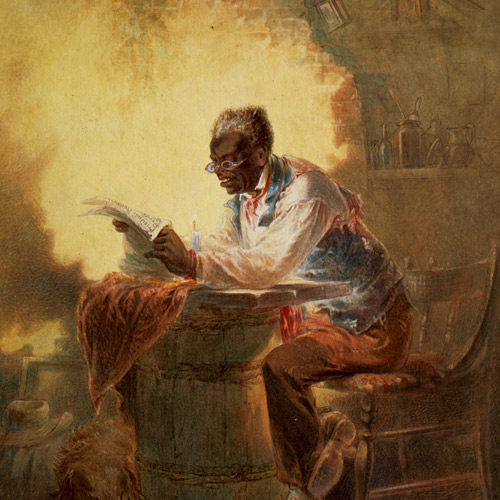

Most armed conflicts are about territory. This one was about ideas. The war would put an end to slavery. It would also create, if painfully, a cohesive single republic — more united than it had ever been before. In fact, the Civil War transformed the United States from a plural noun to a singular one. Before, you would say the United States “are.” Ever since the war, we say the United States “is.”

War became inevitable in December 1860, when South Carolina declared that it would no longer be a part of the United States. Abraham Lincoln had just been elected president, and the Southern states were convinced he would immediately outlaw slavery, on which their economy depended. They resolved to leave the Union rather than have their way of life overthrown. In February 1861, South Carolina and five other states announced that they were now the Confederate States of America. U.S. Army forces had to retreat to Fort Sumter, a granite fortification in the harbor of Charleston. When the forces refused to leave Fort Sumter, state militiamen waited, wore them down by preventing supplies from getting through, and then opened artillery fire on them. The bombardment lasted for 33 hours, until 4,000 shots and shells set Fort Sumter on fire. Finally, the U.S. flag came down, and the Fort surrendered.

No one imagined how long and devastating the war would be. The first big battle was fought in July 1861, at Bull Run in Virginia, near Washington, D.C., where Union troops attacked Confederate forces in hopes of putting a quick end to the conflict. The Confederates withstood the assault and then counterattacked, and the battle turned into a rout of the Union forces. Many hundreds on both sides were killed, and thousands more were injured. Americans began to see what a long nightmare they had trapped themselves in.

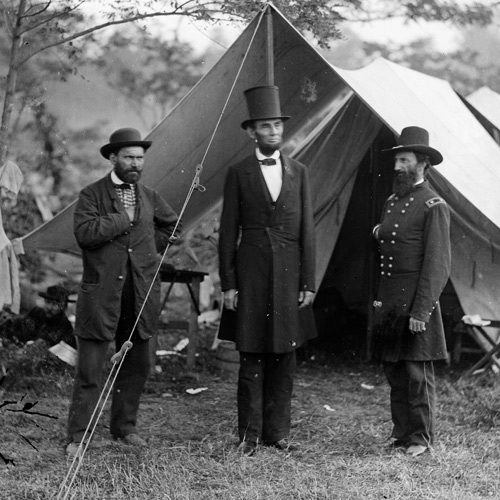

For more than a year after that, Southern troops won victory after victory under a brilliant general, Robert E. Lee, while Lincoln was disappointed by one irresolute Union general after another. One of the first big wins for the North was at The Battle of Antietam, in September 1862. The day it was fought remains the bloodiest day in American his- tory, with 23,000 casualties. Antietam turned a corner for the Union by stopping a northward advance by Lee’s army, and that victory gave Lincoln the confidence to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. On September 22, 1862, he made the sweeping, revolutionary announcement that all slaves in Confederate states would be free as of the following January 1.

Since the Proclamation applied only in states the federal government had no control over, it didn’t really free any- one except in a few Union-occupied parts of Confederate territory. But it told the world — and the captive blacks of the American South — that the war was not simply about preserving the Union. It was undeniably about slavery.

The war dragged on, with both sides more determined than ever after the Emancipation Proclamation. A turning point was reached in early July 1863, when Confeder- ate troops that had invaded the North were turned back in the epochal three-day battle in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, while in Mississippi, Union forces took control of the city of Vicksburg, freeing the Mississippi River from the Con- federacy. As President Lincoln put it, “The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea.” That fall he delivered his great speech at the battlefield in Gettysburg, where 170,000 soldiers had clashed and 7,500 had been killed, saying “that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

Many thousands more were yet to die, though. Lincoln finally found the commanding general he had been looking for in Ulysses S. Grant, and Grant pursued a relentless war of attrition against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, while General William T. Sherman cut a crippling swath through Georgia, devastating the heart of the deep South. The war dragged on until April 1865, when Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Just a week later, President Lincoln was assassinated by an enraged Confederate sympathizer, John Wilkes Booth.

The wounds left by the war did not quickly or easily heal. Reconstruction, a bitterly opposed attempt by the North to remake the South, lasted until 1877 and ultimately failed.

The Civil War brought an end to slavery and reunited the nation, but the pain of reconciling the differences, many of which began with the birth of the republic, lingers still. The war made our motto true E pluribus unum — from many, one — but the work of making us one is never complete.

8 Things You Didn’t Know About the Marines

The phrase “The United States Marine Corps” immediately conjures a number of images and ideas. Toughness. Honor. Tradition. And while that reputation can be traced back to 1775, the “Act for establishing and organizing a Marine Corps” was signed by President John Adams on this date, July 11, in 1798. On its 220th anniversary, we look some of the longstanding traditions that make the Marines the Marines. Some are reflected in the modern culture of this military branch, while others are just downright peculiar.

1. The Marines Have Two Birthdays

The modern Marine Corps descended from the Continental Marines assembled under the Continental Marine Act of 1775, which was initiated by the 2nd Continental Congress on November 10th of that year. Though the Continental Marines were disbanded at the end of the Revolution, the United States Marine Corps still commemorates November 10th as their official creation.

The Marines were “reborn” in 1798. The creation of the United States Navy and Marine Corps grew out of clashes with the French navy during the French Revolutionary Wars. An act of Congress formed the Navy in 1794, with Marines recruited to serve on newly created ships by 1797. Adams signed the “Act for establishing and organizing a Marine Corps,” authorizing a battalion of 500 privates along with a major and other officers. Revolutionary War veteran William Ward Burrows was made an initial major. Marines would serve in the Quasi-War, that undeclared war between the new French Republic and young United States that occurred between 1798 and 1800.

2. Why the Marines are “Marines”

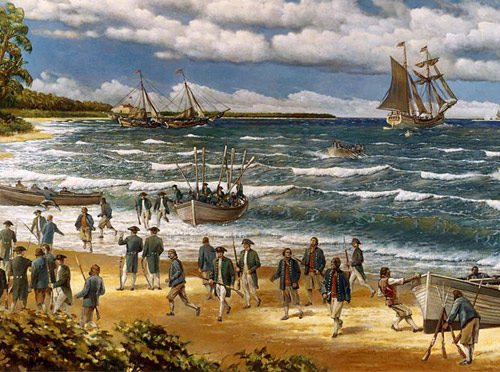

The term Marine came from the type of infantry that supports naval operations. The Marines of the American Revolution typically mounted amphibious assaults, landing from tall ships to conduct raids in locations like British ports in the Bahamas. During the Barbary Wars against piracy that ran from 1800 to 1815, Marines frequently fought in ship-to-ship battles, boarding vessels to capture them.

3. Thomas Jefferson Chose the D.C. Barracks Site

In 1801, President Thomas Jefferson and Burrows, now Lieutenant Colonel Commandant of the Marine Corps, chose the site of the Marine Barracks in Washington, D.C. A National Historic Landmark, it is still in use today as the official residence of the Commandant, the home of the U.S. Marine Drum and Bugle Corps, and the main ceremonial location for the Corps.

4. The Dress Blues Were Overstock

Sometimes a uniform is carefully designed and thought out over time. And sometimes, you take what you can get. The familiar ceremonial “dress blues” of the Corps adopted their look from an overstock of blue jackets with red trim that Burrows received upon his original appointment to major.

5. The First Marine Sword Was a Gift

While battling Barbary pirates in Africa, First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon, eight other Marines, and over 300 mercenaries of Arab and European origin mounted an assault on Tripoli in an attempt to liberate the captured crew of the U.S.S. Philadelphia. Though they did not take the city, deposed Prince Hamet Karamanli allegedly presented a Mameluke sword to O’Bannon after the Battle of Derna. The sword story sparked the tradition of Marine officers wearing swords in dress blues.

6. Why Tripoli Is in the Marine Hymn

The other lasting legacy of the action was the inclusion of the lyrics “to the shores of Tripoli” in the Marines’ Hymn by Thomas Holcomb in 1942. The Hymn is the oldest of any of the songs that represent the U.S. Armed Forces. The original music was written in 1867 by Jacques Offenbach, but it wasn’t adopted as the official music of the Corps until 1929.

7. There Are a Lot of Active Marines

Today, the USMC boasts 186,000 active Marines with around 38,500 reserves. Roughly 7.6% of today’s Marines are women. Of the more than 22 million veterans living in the United States as of 2014, less than 1% were Marines.

8. They Perform MANY Jobs

Over 336 MOS (military operational specialist) codes, or job types, are presently available in the Marines; paths include everything from infantry to avionics to 60 different categories of linguistics. Even as new avenues for duty continue to expand, it’s safe to say that, even after more than 200 years, the Marines continue to pursue high standards in their service to the country.

8 Other Things That Happened on the Fourth of July, and One That Didn’t

Independence Day is such an institution in the United States that when we hear “Fourth of July,” many of us think of it first as the name of a holiday and not simply — as it is in so many other countries — a calendar date. Considered the birthday of America, the holiday commemorates the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, but in the more than two centuries since, it isn’t the only notable event to have happened on that date.

Here are eight other things that happened on that day, plus one thing that surprisingly didn’t happen on the Fourth of July.

1. 1802: The Military Academy at West Point Opens for Instruction

What began as fortifications at the mouth of the Hudson River in 1778 is now the oldest continuously occupied military post in the U.S. In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson signed the Military Peace Establishment Act into law, which in part established a new U.S. Military Academy at West Point whose primary purpose at the time was to train expert engineers. On July 4 of that year, the new academy formally opened for instruction.

Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee were both West Point graduates, as was Confederate President Jefferson Davis. West Point grads played a big role in the U.S. military during World War II: General George Patton, General Douglas MacArthur, and General (later President) Dwight D. Eisenhower were all alumni.

West Point grads have distinguished themselves outside the military, too. Other successful alumni include astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, Pittsburgh Steelers left tackle Alejandro Villanueva, and Duke University head basketball coach Mike Krzyzewski.

2. 1817: Construction Begins on the Erie Canal

It took eight years for engineers and laborers to create the 4-foot-deep, 40-foot wide, 363-mile-long canal that would connect Albany and the Hudson River to Buffalo and Lake Erie. But it was worth it: This massive public works project opened up travel to the west and was a key influence in turning New York City into America’s principal seaport and a center of business and finance.

In 2000, the U.S. National Parks Service designated the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor.

3. 1826: Thomas Jefferson Dies

It seems a poetic justice that the man most responsible for writing the Declaration of Independence should die on the 50th anniversary of its adoption. Though his exact cause of death at age 83 is unknown, his health had been in steady decline since 1818.

4. 1826: John Adams Dies

The second and third presidents of the United States died within five hours of each other. Though they fought side by side to create a free America, after they had achieved that goal, they discovered they had very different ideas about what these new United States should look like. They became bitter political rivals for decades, only rekindling their friendship later in life.

It’s a part of American legend that the 90-year-old John Adams’ last words were “Jefferson still survives,” not knowing that the younger man had passed earlier that day, but the veracity of this legend is questionable.

5. 1845: Henry David Thoreau Moves to Walden Pond

The American transcendentalist began his two-year experiment in simple living on the Fourth of July. On that date, he moved into a small cabin he had built himself on the shores of Walden Pond, near Concord, Massachusetts, on land owned by fellow philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. In 1854, he published his record of the experience in Walden, or Life in the Woods to moderate success.

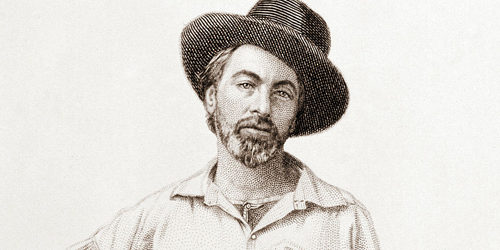

6. 1855: Leaves of Grass published

Though the 795 copies of the first edition of Leaves of Grass — which Walt Whitman designed and published himself — included only 12 poems over 95 pages, it changed the course of poetry in America for good. Whitman added, revised, and republished his poems throughout his life so that, by the time he died and after several editions, Leaves of Grass contained 389 poems.

7. 1939: Lou Gehrig’s “Luckiest Man” Speech

On May 2, 1939, New York Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig ended his record-setting streak of 2,130 consecutive games by benching himself for poor play. He would never play again. A month and a half later, he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

On July 4, the Yankees held Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day in a sold-out Yankee Stadium. Gehrig, who was petrified of crowds, wasn’t originally expected to speak, but such an outpouring of love pushed him to it. That afternoon, he stepped up to the mic and delivered his “Luckiest Man” speech, which is still considered one of the most moving speeches ever given at a sporting event. In it, he acknowledged not only the fans and the other players, but even the groundskeepers and his own mother-in-law.

8. 1997: Pathfinder Lands on Mars

After a six-month journey, the first Mars Pathfinder landed on the Red Planet on July 4, 1997. It became the base station for the free-range robotic rover Sojourner — Earth’s first (successful) interplanetary rover. NASA received its first picture of Mars at about 9 p.m. that day.

Pathfinder and Sojourner collected 2.3 billion bits of data during their lifespan and sparked two decades of Mars exploration. Though the mission was only supposed to last up to 30 days, NASA continued to receive data for 83 days.

Not on the Fourth of July: The American Colonies Declare Independence from Great Britain

The members of the Second Continental Congress voted 12-0 with one abstention (New York) on a motion to officially separate the American colonies from British rule on July 2, 1776. By July 3, two Philadelphia newspapers, the Pennsylvania Evening Post and the Pennsylvania Gazette, were already reporting that “the Continental Congress declared the United States Colonies free and independent States.” That same day, John Adams wrote home to his wife, Abigail: “The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.” Adams believed the Second of July, not the Fourth, would become a national holiday.

What we celebrate now as Independence Day marks the day in 1776 when the final edited version of the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress, though the final signatures on it wouldn’t be collected until early August.

50 Years Ago: Taking On the Weapons Industry

Nuclear physicist Ralph Lapp helped to develop the atomic bomb before petitioning against its use in 1945. Lapp toured the country in the 1950s and ’60s lecturing about nuclear radiation and civil defense, but in 1968 he penned the Post editorial “The Weapons Industry Is a Menace,” taking acute aim at the so-called military-industrial complex. Lapp decries the burgeoning “defense socialism” in the U.S., claiming Eisenhower’s famous 1961 warning had come to bear in a nation whose welfare was “permanently tied to the continued growth of military technology and the continued stockpiling of military hardware.” Lapp’s rebuke of defense spending during the Cold War highlights the problems with weapons excess that are still debated 50 years later.

“The Weapons Industry Is a Menace” by Ralph E. Lapp (June 15, 1968)

The United States is becoming a weapons culture. The health of our entire economy has come to depend on the making of arms. The machinery of defense, lubricated by politics and technology, has become a juggernaut in our society. Pressures exerted by the giant corporations that compose our military-industrial apparatus are felt in the Pentagon, in the White House and in Congress. Congressmen are re-elected depending on their success in winning defense contracts for their constituencies; government funds support vast military research projects on campuses across the country; the scientific community has been largely corrupted or silenced by military domination.

President Eisenhower warned of this ominous trend in his farewell address back in 1961: “In the councils of Government we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

That warning has become the present reality. Since the end of World War II, and especially since Korea, the manufacture of arms has ceased to be an emergency measure whereby private firms do their bit for Uncle Sam. Instead. many U.S. corporations have become primarily arms makers. Their business and their profits depend on winning more and bigger contracts from the Department of Defense. Some companies, like North American Rockwell, General Dynamics and McDonnell Douglas, exist almost entirely on government arms contracts. Without this money many of them would go bankrupt. and places like Southern California or the state of Washington would become economic disaster areas.

Consider, for example, a single company — Lockheed Aircraft. In the past seven years this California-based concern has won a total of $10.6 billion in defense contracts. Uncle Sam provides 86 cents of every dollar of its corporate sales. Lockheed is not just an isolated example. During these same seven years 38 companies each have done more than one billion dollars of business with the Pentagon.

No nation can devote so much of its ingenuity, manpower and resources to the works of war without being deeply changed in the process. Our commitment to weapons making has distorted the free enterprise system of our economy into a kind of “defense socialism.” a system in which the welfare of the country is permanently tied to the continued growth of military technology and the continued stockpiling of military hardware.

This massive “peacetime” commitment to arms is new to the American experience. When one looks back and surveys the postwar years. one startling fact emerges: During these years the United States has devoted one trillion dollars to its national security! And half of this vast expenditure occurred during the Kennedy-Johnson Administrations.

These billions of dollars have meant jobs for many Americans — for electronics specialists in Boston’s Route 128 necklace of defense plants; for rocket men in factories spread out over Utah’s broad valleys; for aircraft workers in Southern California. Texas. Georgia, Washington. Kansas and Missouri.

President Eisenhower omitted any reference to political influence in his indicting phrase, “the military-industrial complex.” but it is the crux of the matter. Powerful members of Congress champion defense systems out of self-interest. Georgia’s defense bounty may be traced, for example, to the power of its Senator Richard B. Russell. who is chairman of the potent Armed Services Committee. Our senators and representatives approve the appropriations that control the fate of many a defense plant. It takes a brave legislator to vote against funds that mean jobs for some of his constituents. He becomes vulnerable not just to the unemployed defense worker but to campaign charges that he failed to support the national security program.

The power of the military-industrial complex has been greatly aided by advanced technology. Science has become the key to modern arms. Today’s weapons systems, especially those involved in hurling nuclear warheads at intercontinental range, are incredibly complex. Nuclear research has fashioned compact packages carrying the explosive power of a million tons of TNT. Chemical and electronic ingenuity have combined to perfect rockets like Minuteman and Poseidon that can carry from 3 to 10 warheads, each dispatched to a separate target. More and more our great national decisions involve complex technology and secret data about weapons.

Consider, for example, the recent decision to build a thin Sentinel system to defend against ICBM’s fired by Red China. This $5 billion project may escalate to $40 billion. Yet the public had precious little to say in this momentous decision. In a sense, even a democracy as modern as ours is dictated to by technology. When a weapons system becomes “ripe,” then it dominates its makers. In the case of ballistic-missile defense, the United States spent $4 billion in research and development, so before the decision to deploy it was made, powerful forces urged its production. Robert S. McNamara, who recently resigned as head of the Pentagon, put it bluntly: “There is a kind of mad momentum intrinsic to the development of all new nuclear weaponry. If a weapons system works — and works well — there is strong pressure from many directions to procure and deploy it out of all proportion to the prudent level required.”

One way to pressure the American people into supporting larger defense outlays is to sound the alarm about Soviet strength. Thus in the 1950s it was alleged that there was a “bomber gap,” and public support was whipped up for mass production of B-47s and B-52s.

Even before the bomber gap vanished into thin air, a “missile gap” was born. John F. Kennedy hammered away at the missile-gap issue in his 1960 campaign, decrying Eisenhower’s years in office as “years the locusts have eaten.” Yet when Kennedy became President and had time to study the available information about Soviet missiles, he discovered that the missile gap was in our favor. Nonetheless, Kennedy pressed Congress for authorization of more Minuteman and Polaris missiles.

Now a new gap is in the making — a “megaton gap.” A megaton means a million tons of TNT, or 75 times more power than the A-bomb that eviscerated Hiroshima. At some time in the future the Soviet Union may be able to hurl more megatons at the United States than we can fire back in return. This does not and cannot alter the fact that a small fraction of the present United States nuclear firepower can knock the Soviet Union out of the 20th century. Having excess kill power — overkill — is not militarily meaningful.

The heart of our strategic policy is our capability to inflict unacceptable losses on the enemy’s homeland. It’s damage, not megatons, that counts. I have calculated that as few as 45 ballistic missiles can strike at 60 million Russians living in 200 Soviet cities. No, my arithmetic is not nutty — each missile can be armed with from 3 to 10 nuclear warheads targeted on individual cities. The total megatonnage in this hypothetical attack amounts to only 21 megatons — roughly one thousandth of that once carried by our SAC bombers. But 21 megatons is the equivalent of 21 million tons of TNT, or 620 times the explosiveness of the combined power of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs.

If my figure of 45 missiles seems too low, then let’s triple it. That figure would amount to less than a tenth of the actual number of missiles in our strategic strike force. Adding more ICBM’s to the U.S. arsenal, or magnifying the megatonnage, does not really alter the nuclear balance of power.

But the very concept of “enoughness” in military power is a punishing blow to the solar plexus of the military-industrial-political complex. Defense affluence is based on open-endedness on there never being enough of anything, even megatons. The United States has already stockpiled over 50,000 nuclear weapons and has a capacity to double this number rather quickly.

The man in the street is not supposed to question matters of national security. But whose judgment is he to trust? The politicians are themselves deeply implicated in the military-industrial complex; the generals traditionally don’t know what the word “enough” means, and industrialists covet contracts.

There is sound reason for gloomy forecasts about defense socialism. The United States cannot afford to lay down its nuclear arms until it is safe to do so — and that day is far from dawning. Force of arms still rules, and the United States has no choice but to maintain its armed vigilance. Moreover, it cannot become complacent about its power to deter war by depending on the status quo. For this reason, military research and development should never cease.

But the need for weapons improvement should not be viewed as a carte blanche for defense industry. Rational determination of force levels is of paramount importance to the nation’s security. Excessive weapons deployment may not only be wasteful, it may provoke competitors to unplanned arms increases, and thus escalate the arms race with no real gain in our national security. But “how much is enough” is the perplexing question that this country has avoided facing squarely.

I admit that precise definition of “enoughness” is impossible. No single person or computer can be relied on to spell out how much is enough. There must always be an insurance factor — a margin for error, but not for irrational excess. Even if by some magical process we could find a neat answer to how much military power is enough, we lack the mechanism in our democracy for a techno-military consensus. Our democracy depends on a system of checks and balances, but such restraints are lacking for the military industrial complex. Our Congress is ever ready to vote for larger defense appropriations; not once since Hiroshima has the Congress failed to fund a weapons system. It has even pushed some that the Defense Department did not want. Under congressional insistence the U.S. spent about $1.5 billion on a nuclear-powered airplane — against the best advice of scientists. When the project was finally abandoned, the money turned out to be a complete loss.

Both Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy were pressured by Congress to deploy a ballistic-missile defense system. Had they yielded and authorized the system in the late ’50s or early ’60s, the resulting radars, computers and missiles would have had to be scrapped as useless. Yet when more advanced systems gave some hope of a thin defense shield, and the Sentinel system was authorized, what did members of Congress do? They immediately demanded a “thick” system — one which Defense Secretary McNamara was careful to point out would he worthless against a massive Soviet attack. Furthermore, McNamara warned it would encourage the Soviets to accelerate their ICBM program, and thus add a new spiral to the arms race.

Twenty-three years of the postwar era have failed to educate the Congress in the realities of nuclear power. We should be considering arms cutbacks, not increases, but this prospect frightens Congress and terrifies the aerospace industry, which is becoming a kind of national industrial welfare program.

There is no easy panacea for correcting America’s techno-military ills. But we must begin by recognizing the inherent dangers to our society if we do not control our arms industries. Public exposure of the problem is essential. The Congress must provide itself with authoritative independent advice on techno-military problems. To this end I would urge the creation of a National Analysis Council to study and report on many of the problems that Congress is now handling in a horse-and-buggy manner. For example, the Congress may soon be asked to fund a new Advanced Manned Strategic Bomber. I would urge that it subject this proposal to a concentrated and objective analysis by a National Analysis Council. so that its full significance and value can be determined for the benefit of all members of Congress.

I would urge that the growth of defense socialism be curtailed by applying geographic and contract controls to all new prime military awards. For example, it might be feasible to limit a corporation’s involvement with defense work by prohibiting the awarding of new contracts when a company already does more than half of its business with the Defense Department.

These are, I admit, inadequate approaches to the overall problem. We cannot treat a cancerous condition so superficially, but we must begin somewhere — and soon. If we perpetuate our weapons culture, we will turn ourselves into a veritable Fortress America, questing for evanescent security and, in the words of John F. Kennedy, “forever racing to alter that uncertain balance of terror that stays the hand of mankind’s final war.”

8 of History’s Most Destructive Lies

These days lying is in the news — practically every day.

Lie was a word that, not so long ago, politicians and the media rarely spoke outright. But under the current administration, the president and the press have repeatedly accused each other of dishonesty. Many of these fabrications are ignored or quickly forgotten by a public that is no longer surprised by mendacity.

But all lies are not equal. And in the media’s frenzy of fact-checking, that’s one fact that’s too often overlooked. Some memorable lies have been spectacularly false but wrought relatively little harm. For example, think of President Nixon’s assertion that “no one in the White House staff … was involved” in the Watergate break-in (August 29, 1972), or President Clinton’s “I did not have sexual relations with that woman” (Jan 26, 1998). They probably changed no one’s mind, and did little to delay the ultimate consequences for those presidents.

But other lies in history not only were whoppers, but also caused untold damage. It’s important that we do not forget these terrible deliberate deceits — lies that were responsible for unspeakable suffering and, in some cases, millions of deaths.

Here are eight lies that had serious, large-scale, long-term consequences. No doubt there are very many more evil fabrications we have overlooked. We welcome your input. It’s important that we never forget how easily and how often mankind has been played for suckers, with disastrous results.

1. “In today’s regulatory environment, it’s virtually impossible to violate rules.”

That’s what Bernie Madoff said in 2007, addressing a conference on illegal practices in Wall Street. Even as he spoke, he was operating the largest Ponzi scheme in history. When it came crashing down the following year, the investment advisor had bilked 4,800 clients of $18 billion.

Result: After confessing that his firm’s asset management was “one big lie,” he was arrested, tried, and sentenced to 150 years in prison. (To date, $11 billion of the lost $18 billion have been recovered and restored to Madoff’s victims.)

2. “There is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction.”

In the aftermath of 9/11, the United States immediately struck back at the terrorist masterminds in Afghanistan. But many people in the Bush administration were convinced that the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein in Iraq was not only conspiring with Al Qaeda but was stockpiling weapons of mass destruction to use against the United States (illustrated in the above quote from Dick Cheney).

Despite there being no credible evidence that this was true — most intelligence and on-the-ground inspections revealed no WMDs — the Bush administration chose to pin its reasons for going to war on information from an Iraqi informant nicknamed “Curveball,” as well as on documents that showed Iraq had obtained a large quantity of uranium for the purpose of making a nuclear bomb. The informant was soon discredited, and the uranium documents were discovered to be obvious fakes, but the wheels were already in motion. In 2002, President Bush told the country that Saddam not only had stockpiled deadly chemical and biological agents, but that he had also been building nuclear bombs. In 2003 the United States launched war against Iraq. It’s not clear who knew the evidence for WMDs was false, or when they knew it. Regardless, the financial and human cost was devastating.

Result: Thousands of Americans and hundreds of thousands, if not more, of Iraqis have died in a war that lasted eight years and cost $2.4 trillion. General Colin Powell, who led the U.S. defeat of Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War, would later bitterly denounce his own speech in 2003 as U.N. Ambassador defending the Bush invasion. America and the world are still living with the war’s consequences.

3. “Cigarette smoking is no more ‘addictive’ than coffee, tea, or Twinkies.”

For years, the tobacco industry assured customers that cigarettes were neither unhealthy nor addictive. The makers of Old Gold cigarettes claimed “Not a cough in a carload.” And in 1994, James W. Johnston, CEO of R.J. Reynolds, told a congressional committee, “Cigarette smoking is no more ‘addictive’ than coffee, tea, or Twinkies.”

The reality, of course, is quite different. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 480,000 Americans die every year from cigarettes.

Result: In 1998, the four largest tobacco companies reached a settlement with 46 states to pay $206 billion over 25 years to help cover the medical costs of smoking-related illnesses.

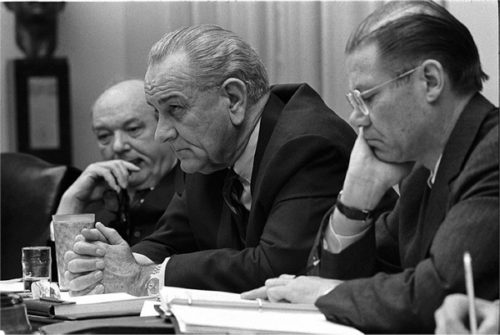

4. “We are not about to send American boys nine or ten thousand miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves.”

In 1964, Americans were concerned about the country’s growing involvement in the Vietnam War. On October 21, 1964, President Johnson assured the country, as he was running for president, that they had nothing to worry about. Despite his words, the following March, he began shipping Americans by the tens of thousands to Vietnam.

Johnson’s statement began a long campaign by our government to lie to the American people about the fact that almost everyone who knew the facts — from the soldiers to the bureaucrats to the president himself — knew that the war was unwinnable. After Johnson left the White House, President Nixon continued the pretense, even secretly expanding the war into Cambodia.

Americans were furious when, in 1971, defense analyst Daniel Ellsberg released military intelligence — known as the Pentagon Papers — that showed the extent of the deception. They realized they’d been lied to about the conflict because neither Johnson nor Nixon wanted to take responsibility for losing an unwinnable war that we never should have undertaken in the first place.

Result: In addition to the 58,000 American lives it claimed, the war produced a chronic mistrust of the government that, for many, continues to this day.

5. “There is no famine or actual starvation, nor is there likely to be.”

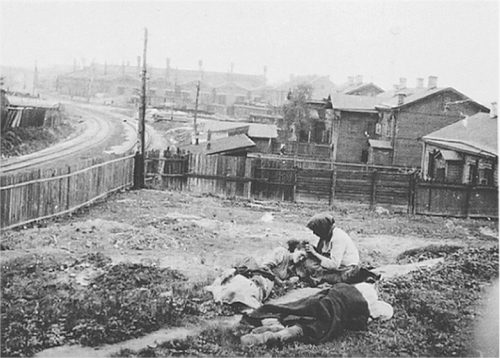

In the 1930s, Joseph Stalin was determined to wipe out private farms in Ukraine and put the population into Soviet controlled communes. He instituted a policy that began starving this region. Ultimately, between two and four million people starved to death. As could be expected, the Soviet government denied any problems. What is surprising is that many western reporters repeated Moscow’s interpretation of what was happening in the region.

Walter Duranty, a reporter for the New York Times, wrote repeatedly that was no famine (those are his words, above). He wasn’t the only reporter who parroted the Soviet’s line, but he was at a prestigious paper and had actually won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of Stalinist Russia. Duranty also justified the brutality of Stalin’s gulag system as a necessary measure that would ultimately benefit the Russian people.

Result: Duranty’s assertions that there was no actual starvation assured western leaders there was no reason to press for famine relief. His reporting helped the world turn away from the deaths and imprisonment of millions.

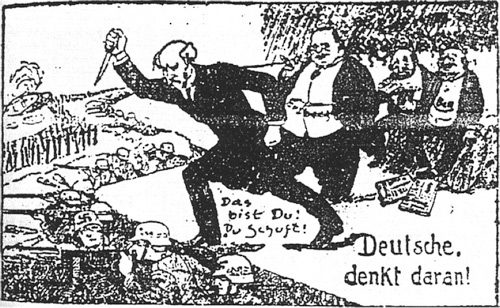

6. “The German Army was stabbed in the back.”

In 1919, General Paul von Hindenburg told the German people why they lost World War I. He said Germany hadn’t been beaten honorably on the battlefield by the enemy, but by radicals and other undesirables back home who’d overthrown the Kaiser’s monarchy and replaced it with a republic. The real reason for the defeat, Hindenburg said, was “The German army was stabbed in the back.”

In fact, the German army had thrown everything it had into one last, desperate chance for victory. By June, they had simply run out of steam. Moreover, the revolution had begun not by civilians but by members of the German military.

But the lie was swallowed by Germans who were convinced that if only the troublemakers could be silenced, Germany would regain its greatness.

Result: The lie fueled the rise of the Nazi party.

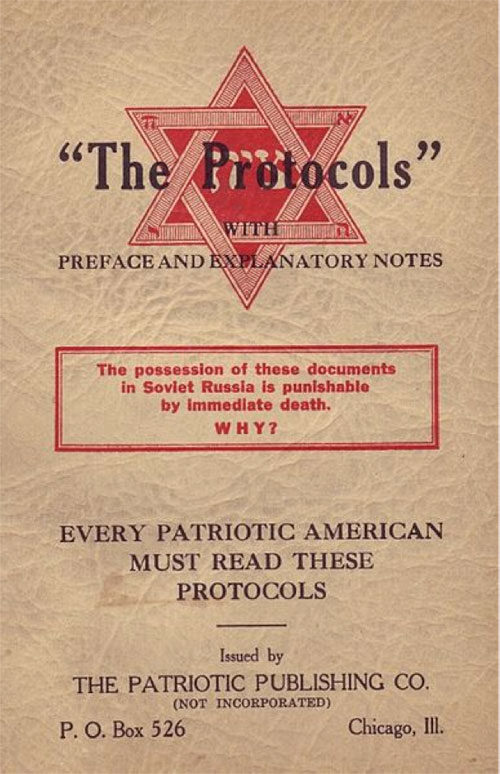

7. “The Jewish Peril: The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion”

In 1905, Russian writer and mystic priest Sergei Nilus claimed that he had proof of a Jewish plan to achieve global domination by corrupting the morals of Gentiles and controlling the world’s media and money. The Jews were also plotting, he claimed, to slaughter Christian children, spread plague, and commit other atrocities.

Despite the fact that the Protocols were shown to be a malicious fabrication, many people stubbornly believed its vile slanders. Henry Ford thought it so important he paid to publish half a million copies. And the Nazis later cited it to justify their slaughter of eight million Jews.

Result: The Protocols continue to be used to fuel anti-Semitic hatred.

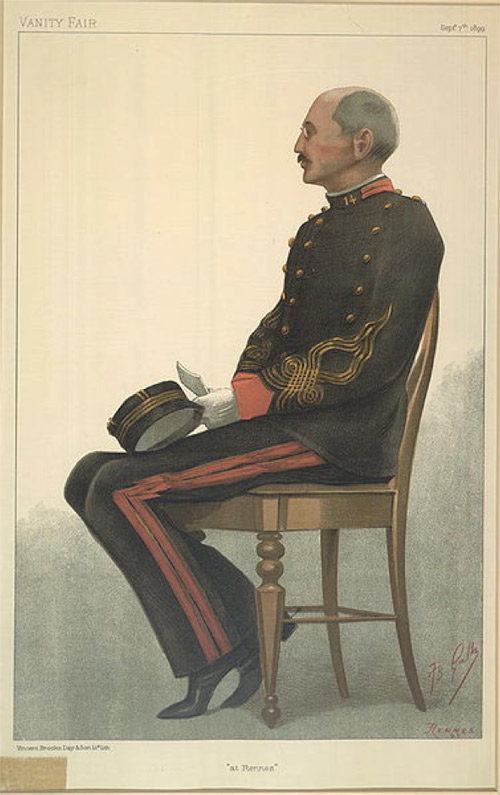

8. “We know Dreyfus is guilty of treason because he ‘made everything disappear.’”

In 1894, French military intelligence officers learned the Germans were receiving secret information about new French artillery. After reviewing possible suspects on the French General Staff, they accused Lt. Col. Alfred Dreyfus. His chief qualification for being suspect was his Jewish faith. He was tried by a military court, found guilty, stripped of his rank, and sent to permanent exile on Devil’s Island off the South American coast.

High-ranking military officials had been determined to pin the blame on Dreyfus. They had secretly supplied the judges with wholly invented evidence. And the fact that there was absolutely nothing that implicated him was actually used against him. The proof of guilt, an officer said, was that “Dreyfus made everything disappear.”

In 1896, new evidence indicated the traitor was actually another officer who was allowed to flee the country. For years, the military ignored the public outcry against Dreyfus’s conviction. Ultimately it yielded to pressure and tried Dreyfus again, and convicted him again.

Result: The lie did more than convict an innocent man. It split the country between social classes, age groups, and political parties. Even after Dreyfus accepted a pardon in 1906 rather than return to Devil’s Island, the case continued to divide the country, and this lack of unity seriously weakened its ability to defend itself in both world wars. (The French military finally proclaimed Dreyfus innocent in 1995.)

Featured image: Shutterstock

Considering History: How Immigration Laws Can Destroy American Families

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton is the first in a series that explores the connections between America’s past and present.

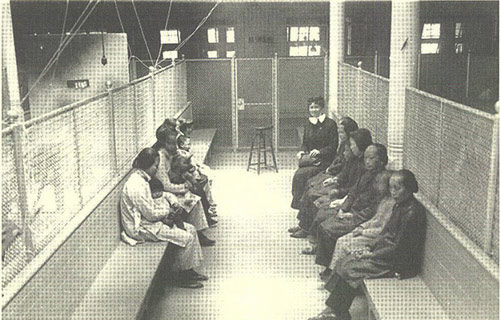

One of the great unknown American short stories, “In the Land of the Free [PDF]” (1912) by Sui Sin Far (Edith Maude Eaton), describes the effects of the first American immigration laws and policies on a Chinese American family. In Far’s story, Chinese American merchant Hom Hing and his wife Lae Choo have immigrated to and live in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. But Lae Choo has returned to China to care for her husband’s dying parents; while there she gives birth to their first child, a son. When she and her infant child return to her San Francisco home, they are detained by customs officers; eventually her son is forcibly taken away from her and held in a detention facility.

After ten long months of efforts to secure his release—“ten months since the sun had ceased to shine for Lae Choo,” Far writes—the family finally succeeds. Yet when Lae Choo reunites with her son, he “shrunk from her and tried to hide himself in the folds of the white woman’s skirt.” The story’s tragic final line is, “‘Go ‘way, go ‘way!’ he bade his mother.”

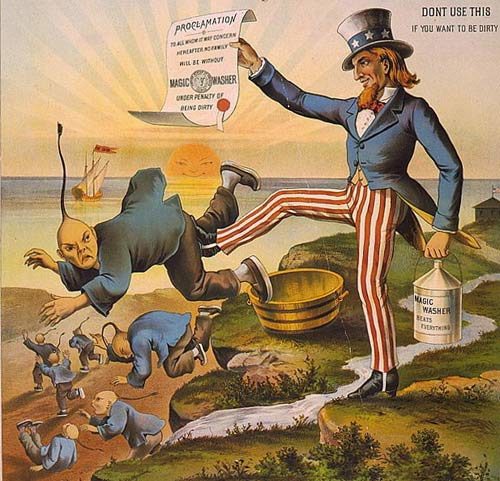

Immigration laws and policies might appear to focus entirely on new arrivals to the United States. But as exemplified by the earliest national immigration laws, the development of immigration policy has also consistently affected families and communities already in the United States. Many elements of these discriminatory first immigration laws were created precisely to disrupt both new and existing immigrant American families, and through them communities deemed less desirable or less “American.”

The first national immigration law was the Page Act of 1875 [PDF], a very specific act that defined three particular categories of arrivals as “undesirable”: those considered convicts in their prior country, forced laborers, and Asian women coming to the U.S. “for the purposes of prostitution.” The third category engaged in stereotypical (and enduring) images of Asian women as by nature “lewd and immoral” (the act’s own terms). But in an era of rising anti-Chinese sentiment, the true goal of that category was to make it more difficult for Chinese Americans to establish multi-generational families and communities: many of the first such Chinese arrivals had been men, and limiting female arrivals would thus limit such multi-generational growth.

In fact many such multi-generational Chinese American families and communities already existed in the United States as of the 1870s. The 1880 census (the first to record ethnic/national identity) identified more than 100,000 Chinese Americans, a number likely much lower than the actual one given the difficulty of documenting those living in crowded mining camps and tenement houses. Limiting future arrivals would not be enough to eliminate, or even necessarily contain, such a significant, longstanding, and rooted American community.

Which is why the next national immigration law, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, went significantly further still. The act deemed virtually every category of future Chinese arrival as now illegal, including “both skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining.” It also made it impossible for any Chinese American to gain citizenship and stripped the citizenship of all those who had already earned it. The act’s preamble argued that Chinese immigration “endangers the good order of certain localities” within the United States, and of course such a sentiment would have to apply to present and past arrivals just as fully as future ones.

Follow-up laws in the aftermath of the Exclusion Act further clarified these goals of dismantling existing families and communities. The Scott Act of 1888 made it illegal for any Chinese American living in the United States to leave the nation and attempt to return, an odious extension of the Exclusion Act designed explicitly to sever multi-national family and community relationships and implicitly to make it far more difficult for Chinese Americans to continuing living in the U.S. The Geary Act of 1892 extended and amplified those difficulties, requiring Chinese Americans to carry at all times a “resident permit” or risk immediate deportation.

Lae Choo and her infant son in Far’s story were thus breaking the law (indeed, likely multiple post-Exclusion Act laws), making them “illegal immigrants” who were officially deserving of whatever punishment the customs officers and the government deemed appropriate. Yet Far’s story underscores two fundamental historical realities: that immigration laws have artificially constructed categories like “legal” and “illegal” through the development of particular, discriminatory immigration laws; and that those laws have been applied not only to categorize certain arrivals as “undesirable” and thus “illegal,” but also and especially to do the same for existing American families and communities.

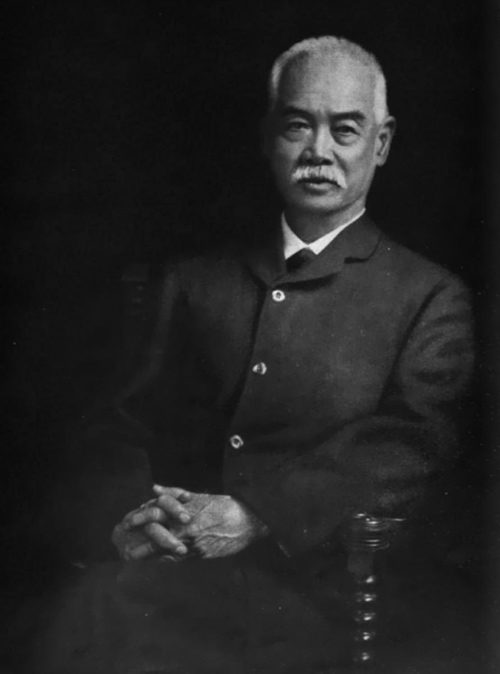

The fictional account of Lae Choo closely parallels a multitude of actual victims of these discriminatory laws. Yung Wing, one of the 19th century’s most famous Chinese Americans, had come to the United States as a teenager, brought to Connecticut by missionaries in the late 1840s. He would go on to become the first Chinese American college graduate (graduating Yale in 1854), an American citizen, and a prominent diplomat and educator. His crowning achievement was the 1872 founding of the Chinese Educational Mission (CEM) in Hartford, a program that brought 120 Chinese young men to the U.S. Yet the school was closed in 1880 due to rising anti-Chinese sentiments, and Yung experienced even more destructive results of the Exclusion era: His citizenship was stripped and he was kept out of the country and separated from his family for years. His wife passed away and his young sons were fostered out to friends. He was never legally allowed to return to the United States.

In contrast to these more exclusionary histories, America has also seen moments and laws with more inclusive visions of immigrant arrivals, families, and communities. The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, for example, prioritized immigrants with existing connections in the United States, focusing on “immediate relatives” such as spouses, parents and children, grandparents, and siblings in an attempt to build upon and strengthen immigrant family and community ties. The 1965 law has made it possible for multi-generational immigrant families from many previously excluded nations and cultures—Chinese Americans among them—to once again develop and flourish in the United States.

These immigration policy choices not only affect the opportunities and experiences of new and future arrivals, but also help create and strengthen a national community in which such families and communities can exist and grow openly and successfully. Every debate over immigration law and policy, such as those unfolding in our own moment, affect American families and communities in purposeful and significant ways. Understanding past laws and how they affected families like the one depicted in “In the Land of the Free” can help us make informed and thoughtful decisions about the effects of immigration on our country and our communities.

Post Puzzlers: January 4, 1873

Each week, we’ll bring you a series of puzzles from our archives. This set is from our January 4, 1873, issue.

Note that the puzzles and their answers reflect the spellings and culture of the era.

RIDDLER

MISCELLANEOUS ENIGMA

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

I am composed of 49 letters.

My 21, 12, 44, 32, 5, 17, was the name of the Spaniard who first discovered that America was not a portion of the Eastern Continent.

My 25, 14, 18, 11, 46, 25, 49, 45, is the name of a planet.

My 4, 28, 41, 47, 8, was the birthplace of Columbus.

My 48, 22, 10, 6, 24, 36, 48, 16, 27, 20, is the name of a city in the United States.

My 25, 40, 13, 17, 34, 31, 39, 7, 12, 29, 28, 38, was the name of a celebrated American general during the Revolutionary War.

My 11, 26, 25, 16, 19, 49, 37, 17, is the name of a high, rocky island noted as the place of exile and death of Napoleon Bonaparte.

My 34, 23, 45, 19, 33, 38, 25, 40, 11, 6, 43, 44, 31, 23, 38, was the name of a Roman king.

My 38, 29, 3, 12, 42, 27, 14, 10, 46, 16, is the name of a river in North America.

My 48, 17, 15, 9, 38, 47, 10, was the name of a President of the United States.

My 2, 23, 46, 30, 49, 34, 35, 33, 11, was the name of a celebrated Roman poet.

My whole is quite a true maxim.

Seaboard, N. C., EUGENE.

ANAGRAMS

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

NAMES OF AMERICAN CITIES

South America.

- See, a boy’s run.

- Move on tide.

- Gay Laura.

- Race Lad.

- Spare pilot.

North America.

- Hill had a pipe.

- We met Sir Ned.

- Worn key.

- Labor time.

- Try to sew.

- No more.

Seaboard, N. C., EUGENE.

CHARADE

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

My first is often found in my second;

My whole a beautiful plant is reckon’d.

Fort Totten, D. T. GAHMEW.

WORD SQUARE

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

- Part of a vessel.

- A tree.

- A female name.

- Used for music.

Fort Totten, D. T., GAHMEW.

CHARADES

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

I.

My 1st is an instrument of punishment.

My 2d is one-third of an ell.

My 3d is often seen in newly-mown meadows.

My 4th is one of the blessings of the night.

My whole is one of Scott’s characters.

II.

My 1st is a personal pronoun.

My 2d is part of the human frame.

My 3d is a product of farms.

My whole, an improving study.

III.

My 1st is a title of respect.

My 2d is part of the verb to be.

My 3d is what we do when taking our tea.

My 4th is a popular dish.

My whole is a State in the Union.

IV.

My 1st is man, expressed in a foreign tongue.

My 2d is the author of many crimes.

My 3d is something we all have but have never seen.

My 4th is a common article.

My whole is the birthplace of many great men.

PROBLEM

WRITTEN FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

If the sides of a triangle be bisected, and perpendiculars be drawn from the points of bisection to the circumference of the circumscribed circle, they will measure 10, 34 and 98 rods, respectively. Required—the diameter of the ciroumseribed and inscribed circles, and the sides of the triangle.

An answer is requested.

E. P. NORTON, Allen, Hillsdale, Co., Mich.

ANSWERS

MISCELLANEOUS ENIGMA—Ill got gains are dearly bought, retribution soon will come.

ANAGRAMS—1. Buenos Ayres; 2. Montevideo; 3. La Guayra; 4, Caldera; 5. Petrapolis; 6. Philadelphia; 7. West Meriden; 8. New York; 9. Baltimore; 10. West Troy; 11. Monroe.

CHARADE—Shad-dock.

WORD SQUARES—

SPAR

PINE

ANNE

REED

CHARADES—1. Roderick Dhu. 1. History. 3. Mississippi. 4. Virginia.

PROBLEM—170 rods the diameter of the circumscribed circle—56 rods the diameter of the inscribed circle—90, 186 and 168 rods the sides of the triangle.

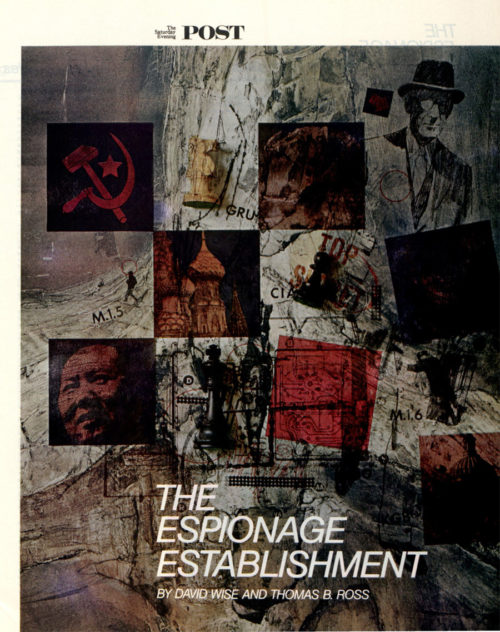

Russia’s Fake News Is Nothing New

When the Post reported on Russia’s intelligence services back in 1967, the KGB’s “Department D” did not get a lot of attention. It was the height of the Cold War (the Berlin Wall had gone up only a few years earlier) and the Soviet Secret Services posed deadly threats to the West. But today “Department D” has a new relevance.

The letter “D” stood for dezinformatsiya, a word coined by Soviet premier Josef Stalin to describe a policy of generating “fake news.” The department’s mission, according to the CIA, was to “defame and discredit” the United States by planting false or misleading articles about America in the media. Each year the department turned out over 350 derogatory news items, designed to “isolate and destroy” the United States.

Dr. Jim Ludes, who recently completed a study on Russian disinformation for the Pell Center, says that back in 1967, the Russians were exploiting racial unrest in America. They planted stories in American papers claiming Martin Luther King was a collaborator and an “Uncle Tom” because they thought his push for unity would strengthen America. After he was assassinated, they used the press to stoke resentment in the black community over his death.

Fifty years later, the old KGB is gone, replaced by the FSB, which does much of the same work and answers solely to President Vladimir Putin, an ex-KGB officer. But as American intelligence organizations have reported, some form of “Department D” is still very much alive.

According to Dr. Yuval Weber of the Daniel Morgan Graduate School of National Security in Washington, D.C., Department D is run by people like Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Putin confidante who ran a “Department of Provocations” — essentially a troll farm used to spread divisive and inflammatory stories before the 2016 presidential election. Weber says, “They engage in those sorts of activities without being official members of government, and if they’re successful can seek quasi-legitimate advertising contracts to cover disinfo operations. If they’re unsuccessful, they move on. It’s like a start-up culture in a sense.”

Russian disinformation, according to New York Times reporter Neil MacFarquhar, has one fundamental goal: “undermine the official version of events — even the very idea that there is a true version of events — and foster a kind of policy paralysis.”

Russia has aimed a torrent of misinformation at the U.S. that has deepened political divisions within our country—and many others — through the creation of fake accounts and the deployment of bots. Russian disinformation has also been at the center of controversy as President Trump and some of his political allies downplay the extent of Russian mischief and interference in our political life.

The openness that characterizes U.S. society has helped the Russians. David Darrow, associate professor of Russian history at the University of Dayton, says, “Our open institutions — our free press and free market … make us stronger, but they pose risks, and the Russians have been quick to exploit them.”

Featured image: Illustration from the “The Espionage Establishment” by David Wise and Thomas B. Ross from the October 21, 1967, issue of the Post.

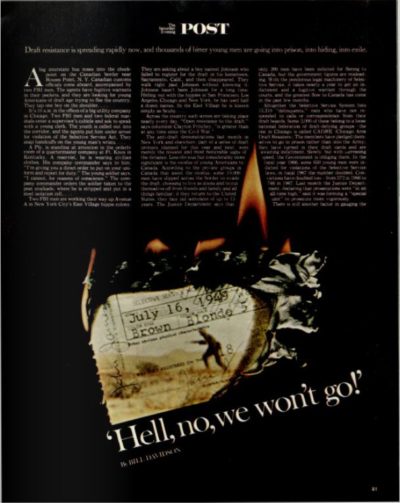

‘Hell, No, We Won’t Go!’: Protesting the Vietnam Draft in 1968

[Editor’s note: This story on the Vietnam War draft was first published in the January 27, 1968, edition of the Post as “Hell, No, We Won’t Go!” We republish it here as part of our 50th anniversary commemoration of the Summer of Love. Scroll to the bottom to see this story as it appeared in the magazine.]

A big interstate bus noses into the checkpoint on the Canadian border near Rouses Point, New York Canadian customs officials come aboard, accompanied by two FBI men. The agents have fugitive warrants in their pockets, and they are looking for young Americans of draft age trying to flee the country. They tap one boy on the shoulder. …

It’s 10 a.m. in the offices of a big utility company in Chicago. Two FBI men and two federal marshals enter a supervisor’s cubicle and ask to speak with a young clerk. The youth is called out into the corridor, and the agents put him under arrest for violation of the Selective Service Act. They snap handcuffs on the young man’s wrists. …

A Pfc. is standing at attention in the orderly room of a quartermaster company at Ft. Knox in Kentucky. A reservist, he is wearing civilian clothes. His company commander says to him. “I’m giving you a direct order to put on your uniform and report for duty.” The young soldier says, “I cannot, for reasons of conscience.” The company commander orders the soldier taken to the post stockade, where he is stripped and put in a steel isolation cell. …

Two FBI men are working their way up Avenue A in New York City’s East Village hippie colony. They are asking about a boy named Johnson who failed to register for the draft in his hometown, Sacramento, Calif. and then disappeared. They walk right past Johnson without knowing it. Johnson hasn’t been Johnson for a long time. Hiding out with the hippies in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York, he has used half a dozen names. In the East Village he is known simply as Scuby. …

Across the country such scenes are taking place nearly every day. “Open resistance to the draft,” says columnist Clayton Fritchey, “is greater than at any time since the Civil War.”

The anti-draft demonstrations last month in New York and elsewhere, part of a series of draft protests planned for this year and next, were merely the noisiest and most noticeable signs of the defiance. Less obvious but considerably more significant is the exodus of young Americans to Canada. According to the private groups in Canada that assist the exodus, some 10,000 men have slipped across the border to evade the draft, choosing to live as aliens and to cut themselves of from friends and family and all things familiar; if they return to the United States, they face jail sentences of up to 15 years. The Justice Department says that only 200 men have been indicted for fleeing to Canada, but the government figures are misleading. With the ponderous legal machinery of Selective Service, it takes nearly a year to get an indictment and a fugitive warrant through the courts, and the greatest flow to Canada has come in the past few months.