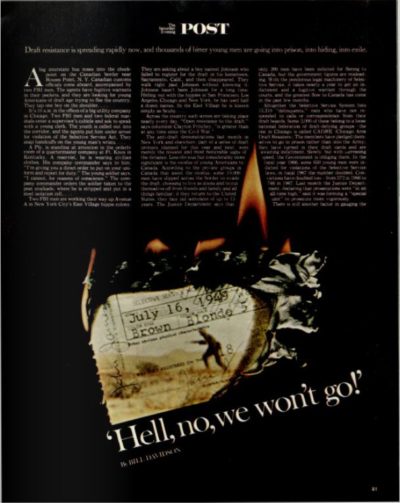

[Editor’s note: This story on the Vietnam War draft was first published in the January 27, 1968, edition of the Post as “Hell, No, We Won’t Go!” We republish it here as part of our 50th anniversary commemoration of the Summer of Love. Scroll to the bottom to see this story as it appeared in the magazine.]

A big interstate bus noses into the checkpoint on the Canadian border near Rouses Point, New York Canadian customs officials come aboard, accompanied by two FBI men. The agents have fugitive warrants in their pockets, and they are looking for young Americans of draft age trying to flee the country. They tap one boy on the shoulder. …

It’s 10 a.m. in the offices of a big utility company in Chicago. Two FBI men and two federal marshals enter a supervisor’s cubicle and ask to speak with a young clerk. The youth is called out into the corridor, and the agents put him under arrest for violation of the Selective Service Act. They snap handcuffs on the young man’s wrists. …

A Pfc. is standing at attention in the orderly room of a quartermaster company at Ft. Knox in Kentucky. A reservist, he is wearing civilian clothes. His company commander says to him. “I’m giving you a direct order to put on your uniform and report for duty.” The young soldier says, “I cannot, for reasons of conscience.” The company commander orders the soldier taken to the post stockade, where he is stripped and put in a steel isolation cell. …

Two FBI men are working their way up Avenue A in New York City’s East Village hippie colony. They are asking about a boy named Johnson who failed to register for the draft in his hometown, Sacramento, Calif. and then disappeared. They walk right past Johnson without knowing it. Johnson hasn’t been Johnson for a long time. Hiding out with the hippies in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York, he has used half a dozen names. In the East Village he is known simply as Scuby. …

Across the country such scenes are taking place nearly every day. “Open resistance to the draft,” says columnist Clayton Fritchey, “is greater than at any time since the Civil War.”

The anti-draft demonstrations last month in New York and elsewhere, part of a series of draft protests planned for this year and next, were merely the noisiest and most noticeable signs of the defiance. Less obvious but considerably more significant is the exodus of young Americans to Canada. According to the private groups in Canada that assist the exodus, some 10,000 men have slipped across the border to evade the draft, choosing to live as aliens and to cut themselves of from friends and family and all things familiar; if they return to the United States, they face jail sentences of up to 15 years. The Justice Department says that only 200 men have been indicted for fleeing to Canada, but the government figures are misleading. With the ponderous legal machinery of Selective Service, it takes nearly a year to get an indictment and a fugitive warrant through the courts, and the greatest flow to Canada has come in the past few months.

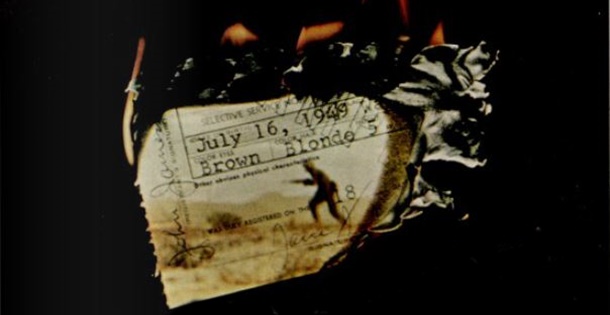

Altogether the Selective Service System lists 15,310 “delinquents,” men who have not responded to calls or correspondence from their draft boards. Some 2,000 of these belong to a loose national federation of draft-defying groups the one in Chicago is called CADRE (Chicago Area Draft Resisters.) The members have pledged themselves to go to prison rather than into the Army; they have turned in their draft cards and are awaiting indictment. Slowly, but with increasing speed, the Government is obliging them. In the fiscal year 1966, some 650 young men were indicted for violations of the Selective Service laws; in fiscal 1967 the number doubled. Convictions have doubled too — from 372 in 1966 to 748 in 1967. Last month the Justice Department, declaring that prosecutions were “at an all-time high,” said it was forming a “special unit” to prosecute more vigorously. There is still another factor in gauging the resistance: More than 22,000 men (not counting veterans) have won classification as conscientious objectors. The rate of conscientious objection is 70 percent greater than it was during World War II. The Selective Service people attempt to soften this by pointing out that there are only 1.7 conscientious objectors for every 1,000 registrants, and they add that only four men in every 10,000 registrants are delinquent. The key word here is registrants. By measuring the resisters against all registrants, the Government manages to disguise the magnitude of the phenomenon. The nation’s 35 million registrants include all men in the United States between the ages of 18 and 45, most of whom are overage, disabled, or deferred — that is, not eligible for the draft anyway.

But even if one accepts the official figures at face value, the problem is still a serious one. The Selective Service System, like most operations of our Government, relies to a large degree on voluntary cooperation; compulsion can go just so far. Now, for the first time in living memory, a sizable number of Americans are refusing to cooperate. Some, of course, are merely cowards trying to save their skins. And some are so intemperate in their opposition that they may be passed off as chronic misanthropes. “The FBI,” says Stuart Byczynski, a draft dodger now in Toronto, “is the new Gestapo, and the country is becoming a vast concentration camp.” But many reveal a strength of conviction that is hard to scorn. “This is my country, and I love it,” says Richard Boardman, who is waiting in Chicago to be prosecuted for draft evasion, “and I will stay here and go to jail if necessary to help correct its mistakes. I accept the general framework of the law, and I accept the penalties for breaking the law.”

The draft evaders, or “non-cooperators,” as some call themselves, vary tremendously in background. There are simple Mennonite farm boys as well as scholars with Ph.D.s. There are Negroes from the ghetto and boys from America’s richest families. Politically, they range from Maoists to Bobby Kennedy Democrats to Goldwater Republicans. It is possible, however, to group these diverse young men in six major categories.

The first is composed of those men who have gone to prison for their anti-conscription activity. These are the elite of draft-dodger society, the folk heroes of the resistance movement. Typical of them is Fred Moore Jr., who was back on the anti-war picket lines just two days after completing his two-year sentence at the Allenwood Federal Prison Camp near Lewisburg, Pa. Moore, a slight, clean-cut 26-year-old from Arlington, Virginia, is a Quaker and a follower of Mahatma Gandhi. He regards himself as an out-and-out pacifist and says he would not even defend himself if attacked.

In 1959 Fred Moore was expelled from the University of California for refusing to participate in the ROTC, which was then compulsory. He joined an organization called the Committee for Non-Violent Action and lived for a time on its farm in Voluntown, Connecticut, helping to raise food for the members and joining in their endless discussions of Gandhi’s principles. He went along on the organization’s “Friendship March to Cuba,” which foundered when the Coast Guard intercepted its boat off Miami.

In 1962 Moore’s draft board classified him 1-A. That prompted him to apply for conscientious-objector status (classification 1-O) so that instead of soldiering he could work in a civilian hospital or a social-service agency. Normally, a youth of Moore’s religious beliefs receives the 1-O classification fairly routinely, but he objected to some of the phrasing in the government form. He crossed out the words “Supreme Being” and substituted “God, which is the power of love.” Moore was investigated by the FBI and had to appear before a hearing officer to explain his religious convictions. In April, 1964, he received his 1-O classification.

“I had a strange reaction to the notice,” Moore says. “I had no feeling of relief or gladness. Instead, I had the feeling that I was a moral coward, and that I had ended up cooperating with the Selective Service System in order to get special status for myself.” He sent his classification card back to his draft board, informing it that it was participating in “the march toward totalitarianism.” He then hit the road, lecturing on peace at college campuses all over the country. He wore sandwich boards reading, LIBERTY YES. CONSCRIPTION NO, THOU SHALT NOT KILL, and DON’T DODGE THE DRAFT; OPPOSE IT.

His protesting ended in June, 1965, when two FBI men came to see him at Pendle Hill, a Quaker study center in Pennsylvania. The government agents told him that they had been sent to give him a last chance. They practically pleaded with him to go to Richmond, where he had been assigned by his draft board to do his alternative service — hospital work. Moore thanked them politely and said no. A few days later he received a registered letter ordering him to surrender himself at the United States courthouse in Alexandria, Va. He did so and went on trial for draft evasion on October 21, 1965.

On his way to the trial he picketed the White House and distributed pacifist leaflets outside the court building. Refusing court-appointed counsel and electing to defend himself, he told Judge Oren R. Lewis that he couldn’t plead guilty because the draft was on trial and not he. His defense was that conscription was unconstitutional because it represented involuntary servitude, as defined by the 13th Amendment. Moore says, “The judge was hostile at first, but then he began to realize I was sincere and trying to live according to my beliefs. He even said so.” The trial lasted three hours. Moore was found guilty and sentenced to two years in the federal penitentiary.

The youth waived his right of appeal and began to serve his time almost immediately on the Allenwood prison farm. There were 80 other Selective Service violators there at the time. “The first six months were the hardest,” Moore says. “I got into an argument with a forger over a program I wanted to see on the television set, and he knocked out my two front teeth. After that I learned that the idea is to do your own time and not bother anyone else. I worked in the prison garden in the daytime, and at night I read or played the guitar and sang folk songs with the other Selective Service violators. Time wasn’t easy, but I learned to adjust to it.” In April, 1967, he was released seven months early on automatic “good time.” He could have been released earlier, but he refused to cooperate with the parole system.

Moore today is back at the old stand, demonstrating against the Vietnam war and counseling opposition to the draft. He has gone to work as office manager for a group called Quaker Action, which dispatches boatloads of medical supplies to both North and South Vietnam, and has married Suzanne Williams, a 19-year-old peace demonstrator who has been arrested and jailed no less than seven times. Moore already has burned his new 1-O draft card, which was sent to him after he got out of jail, and he fully expects to be prosecuted a second and maybe even a third time. He says, almost casually, “I’m perfectly willing to go to jail again for my beliefs.” A Justice Department official says, “This boy is either nuts or so goddamn sincere you have to respect him — but what can we do but throw the book at him again?”

Less sincere and more elusive is the second category of draft evaders, “the Underground.” These are the young men, registered and unregistered, who hide out in the ghettos and hippie colonies of the major American cities. No one in the Government will even guess at how many of them there are, but the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors in Philadelphia estimates that they probably number in the thousands. Certainly they make up a good proportion of the 15,310 Americans listed as “delinquent” by Selective Service.

Many in the Underground have been runaways and “floaters” since their late teens. The Negro youngsters wander from tenement to tenement in the ghettos, where itinerant boarders are common, and no questions are asked. The whites are hippies or disguise themselves as hippies and blend into the anonymity of “crash-pad” living.

In New York’s East Village, the Underground member named Scuby was sitting in a delicatessen eating a pastrami sandwich. “Man,” he said, “there are fifty of us within two blocks of here.” A few minutes before, the two FBI men had passed him without recognizing him; they were showing his picture to shopkeepers and asking for him by the name of Johnson. But the picture was not recent, and Scuby now has a full, reddish beard and wears dark glasses.

He spoke of his background — he came from a “typical middle-class materialistic family,” and when he first “took off,” as he put it, he joined the hippie colony in Venice, Calif. Afterward he floated to other hippie settlements around the country, leaving no trail and never once telling his family where he was. “My father’s a fink,” he said. “He’d turn me in to the feds.”

Scuby doesn’t participate in hippie demonstrations or anti-war protests. “The idea is to play it cool,” he said, “and never do anything to call attention to yourself. Another thing you got to be careful about is not to get high on acid, because you might lose control and say something to give yourself away. You never know who’s a fink for the feds.” Scuby expressed no convictions about pacifism or the Vietnam war. He simply said, “I got better things to do than get shot at by a bunch of Viet Congs.”

Many of the young men in the third major category of draft resisters — those who leave the country — share Scuby’s nonideological, live-and-let-live attitude. This reporter encountered a high percentage of misfits among the fugitives in Canada. Many had records of family conflict and had moved often from one school to another. Nearly all had had 2-S student deferments and hadn’t thought seriously about their personal convictions until the 2-S was revoked. At least a dozen youths claimed they had considered going to jail but had decided against it on the grounds that they just weren’t up to it.

Canada is a natural haven for these young men. Some flee to France or South America, but most find it simplest to cross the Canadian border, knowing that Canadians on the whole are not enthusiastic about the Vietnam war, and that Canada will extradite criminals only for offenses that are also illegal in Canada — since Canada has no draft, draft evasion is not a crime there. Vancouver is an entry point for West Coast evaders and Montreal for fugitives from the East Coast. But, except for menial jobs, employment in Vancouver is tightly controlled by the unions, and the use of French in Montreal presents a language problem for the average American. So Toronto, a cosmopolitan, English-speaking city with an American flavor, has become the center of the draft-dodger community.

One of the more impressive of the Toronto refugees is John Phillips, a tall, blond, 22-year-old Quaker from Algona, Iowa. Phillips’s pacifism is founded in his religion, and ordinarily he would have had little trouble obtaining the conscientious-objector classification he applied for. But he bewildered the five farmers on his rural draft board; he was the first objector they had encountered, and they didn’t know what to make of him. “They called me a coward and a Communist,” Phillips says, “and when they learned I had covered the Selma, Alabama, civil-rights march as a photographer, they said, ‘Oh, so you went down there to help those niggers.’ I told them I’d go to Vietnam as a combat photographer, anything so I wouldn’t have to kill, but they didn’t believe me. For the first time in my life I broke down and cried.”

Phillips filed an appeal and went so far as to report for his preinduction physical examination. He spent the night in a barracks at Fort Des Moines, where the other draftees — until they were stopped by an officer — tried forcibly to shave him from head to toe. That decided Phillips. He married his fiancée, also a Quaker, and they left immediately for Canada. Today his wife, Laura, is a social worker in the Toronto slums, and Phillips is a photographer for an agency of the Canadian Government.

Another young man who made his decision under duress is 22-year-old Michael Miller (not his real name). A student at Penn State and the City University of New York, Miller developed such strong convictions about the U.S. involvement in Vietnam that he refused to cooperate with the Selective Service — even though he has a physical disability that probably would have kept him out of the Army anyway. He decided to go to jail, and his father, a bombardier in the Army Air Corps in World War II, called him a Communist and kicked him out of his house. Then Miller’s wife, who was pregnant, told him that his going to jail would be unfair to her, so they went to Canada. Miller genuinely grieves about his permanent exile from the United States. “I miss being out of the mainstream,” he says. “I miss not being able to go to my parents’ twenty-fifth wedding anniversary and my sister’s wedding. I miss not being able to go home again.”

But Miller’s attitude is not a common one in Toronto. Most of the draft dodgers there have turned against their country completely. They make statements like “They ought to tear down the Statue of Liberty because it doesn’t mean anything anymore.” The left-wing draft dodgers say they don’t want to live in the United States anymore because it has become a “fascist dictatorship no better than Hitler’s Germany.” The right-wingers say they have fled from “a collectivist tyranny no better than Soviet Russia.”

Typical of the latter is 20-year-old Stuart Byczynski, a thin, intense, balding young man who wears glasses. Byczynski was born into a rigid, Catholic, New Deal-Democrat family in Parkville, Maryland, but was in constant revolt against his parents’ religious and political beliefs. He left the Catholic Church and became a Unitarian when he was 17, and in 1964 he campaigned for Barry Goldwater and other conservative Republicans.

“I believe in the freedom of the individual,” he said, “and Big Government in the United States is taking away all our freedoms. It bleeds us to death with taxes, it tells us at what age we can drink whiskey and drive a car, it spends a lot of money forcing artificial racial equality. Even while I was still in high school, I decided no government was going to tell me I couldn’t pursue my chosen profession and would have to sleep on cots with a lot of other people. My sole reason for going to college was to avoid the draft as long as possible with a 2-S student deferment.”

At the University of Baltimore, he did well for four semesters, but then fell from the top third of his class and lost his deferment. He filed an appeal but only to gain a delay until May, 1967, when he had scheduled his flight across the border. On May 21 he rented an apartment in Baltimore and moved out of his parents’ home, telling them that he wanted to live alone for the summer. On May 28 he took a circuitous route to the Baltimore bus station and, to foil the FBI, bought a round-trip ticket. But the FBI never came near him. He arrived in Montreal on May 29, celebrated his 20th birthday alone at the YMCA, and then took another bus to Toronto. There he contacted the Toronto Anti-Draft Programme, which provides legal advice, money, room and board, and an employment service for newly arrived fugitives from the U.S. The organization, run by American draft dodgers but financed mostly by Canadian peace groups, advised him to go back to Buffalo, New York, by plane, and then reenter Canada as an immigrant through the Toronto airport. He did so and then told his parents what he had done. “Their reaction,” he said, “was ‘Sob, sob, where have we gone wrong?” Today Byczynski is working as a reporter for a newspaper in a small city in Ontario. He makes less money than he did in the United States, but, he says, “the taxes are lower, and this country is freer.” Says a former employer in Baltimore: “I’m not surprised at what Stuart did. He always was trying to escape from reality.”

The war resisters in the fourth category do not generally enjoy the luxury of escape. These are the young men who have already entered the armed forces and then decided they couldn’t fight in Vietnam. Their only recourse is to desert (which very few do), or to apply for a conscientious-objector discharge (which are rare; the Army approves less than five percent of the applications). If the young man persists, the usual result is a prison term for disobeying orders. The Department of Defense says it has about 400 C.O. applications pending. The Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors insists, on the basis of its correspondence from servicemen seeking legal help, that the figure is much higher.

One of the most interesting cases in this category involved Michael Wittels, who now is 28 years old and a successful young artist in Philadelphia. Wittels, never a peace activist or protester during his years at Cheltenham High School and the Philadelphia College of Art, joined the Army Reserves and was assigned to a quartermaster company in 1962. His six months of active duty at Fort Knox, Kentucky, were uneventful. He was a good soldier and was promoted to squad leader when the company took heavy weapons training at Fort Polk, La. “But suddenly,” Wittels told me, “the whole thing jumped up and hit me in the face. An instructor was demonstrating a new rifle, and he said, ‘This weapon can tear a hole the size of a fist in a man.’ At that moment I knew I could never kill — that I was a conscientious objector at heart.”

Wittels finished his active duty, but he continued to brood about his convictions, even while faithfully attending his reserve meetings. Finally, in June, 1965, he sought legal advice from the Friends Peace Committee and learned that he could apply for a conscientious-objector discharge. He painstakingly filled out the complicated application, and on August 25, 1965, he turned it in to his company commander.

Six months went by and Wittels heard nothing about the application, though he kept writing to all the higher reserve echelons. In January, 1966, he stopped going to reserve meetings and returned his Army pay checks. In March, the application was turned down. Then he was demoted from Pfc. to Private and, as a punishment, was ordered to report to Fort Knox for 45 days of active duty. He did so, arriving in civilian clothes. He explained his position to his new company commander, a young Negro officer named Capt. Albert Thurmond. “He was very kind and polite,” said Wittels, “but he didn’t know what to do about me, since I told him I could not put on my uniform and serve. He sent me to see the adjutant general and two chaplains. They all tried to talk me into taking the easy way out by putting on my uniform and serving the forty-five days. They didn’t even seem to listen when I told them I would not retreat from my stand.”

After three days, according to Wittels, Captain Thurmond called him into the orderly room, sighed, and gave him a direct order to put on his uniform and report for duty. When Wittels respectfully refused, he was taken to the stockade, where a sergeant told him, “We’ve had your kind in here before, and we’re going to break you.” He was stripped of his shirt, shoes and socks and locked in “The Box,” a 6-by-8-foot isolation cell with nothing in it but a Bible and a steel slab for a bunk. The guards kept him standing until 2 a.m., when he was sent to take a shower. When he got back to the cell, his blanket was gone. It was a cold night, but a guard said, “You don’t want that blanket. It says U.S. Army on it.”

Wittels says he was in “The Box” for three days, during which he was fed bread, dry cereal, and cabbage. On the third day the confinement officer, a six-foot, seven-inch Negro captain named Wyatt Minton, came to see him. “Just put on the regular stockade fatigue shirt, not your uniform, and I’ll let you out of here. I need the space.” Wittels agreed, and was put in a 24-man cell with the general prison population. There were eight other C.O.’s in the stockade. Two weeks later he went on trial for disobeying his company commander’s direct order to put on his uniform. He was found guilty and sentenced to six months at hard labor. Wittels was returned to a solitary cell on the grounds that “he would contaminate the other prisoners.” The quarantine didn’t work. The other prisoners and even the guards came to admire Wittels’s uncomplaining courage, and they smuggled food and books in to him. Six weeks later Captain Minton sent for Wittels. “I hear you’re a damned fine artist,” he said. “I’m going to let you out around the base to do paintings to decorate the stockade. All you have to do is sign a statement saying you’ll obey stockade rules.” Wittels signed the statement.

On February 6, 1967, the end of his sentence, Wittels was released from the stockade. He went back to his Fort Knox company where an officer again ordered him to put on his uniform and report to a duty station. Again Wittels refused, and he was returned to the stockade. This time Wittels faced a general court-martial and a sentence of five years at Fort Leavenworth. He was made a maximum-custody prisoner, often with handcuffs and an armed guard.

But without his knowledge a series of events were taking place far from Fort Knox. Wittels’s mother had appealed to Congressman Richard S. Schweiker, a Republican from Pennsylvania, who demanded that the Army investigate. The Army told him it was processing Wittels’s new application for a conscientious-objector’s discharge. And then a hearing officer ruled that the charge pending against Wittels was unsupported. He was released to perform noncombatant duties on the base. After 26 days Wittels was sent home. In July, 1967, he received a general discharge “under honorable conditions … by reason of conscientious objection.” Later one of the Fort Knox stockade guards wrote to him: “What you went through here took more guts than going to Vietnam.”

Wittels, of course, could have avoided his ordeal if he had obtained conscientious-objector status before going into the Army. This type of war resistance is perfectly legal. The more than 22,000 men who have been classified as C.O.’s by their draft boards make up the fifth and sixth categories of war resisters — the two kinds of legitimate C.O.’s recognized by the Selective Service System.

One kind is the men who are classified 1-A-O. The 1-A-O’s go into the Army as draftees along with the 1-A’s, but they are not required to handle weapons, and they perform only noncombatant duties, usually in the Medical Corps. Members of churches such as the Seventh-Day Adventist almost automatically get 1-A-O status from their draft boards when they apply for it; others have to prove their case. All 1-A-O’s — there are 4,500 of them — take their basic training in two 400-man companies in the Army Medical Training Center at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Tex. They are treated the same as other soldiers, except that they get no weapons training. After training, most are assigned as medical corpsmen with Army units in the field, including Vietnam. Col. C. C. Pixley, commander of the Army Medical Training Center, says, “These people are among the best soldiers I have ever known.”

Sgt. Richard Enders epitomizes the C.O. in the Army. A Seventh-Day Adventist from Longview, Washington, Enders was classified 1-A-O and sent to Fort Sam Houston. From there he went to Vietnam and was assigned to the 346th Medical Dispensary in Can Tho, the heart of the Viet Cong-infested Mekong Delta. Enders not only tended wounded GI’s but consistently volunteered for expeditions on which teams of Army Medical Corps specialists go into the countryside under heavy guard and treat the civilian population in Vietnamese villages. There was only one other C.O. in Enders’s outfit, but, he says, “no one thought of us as being different from anyone else.”

Getting to be a 1-O, the other type of legitimate conscientious objector, is a bit more complicated. The 1-O, after he receives that classification from his draft board, does not serve in the Army but puts in two years of so-called “alternative service” as a civilian. The type of work he does is severely restricted and must be approved by the draft board. Usually it’s duty of some sort in a civilian hospital or social-service agency. Although 1-O’s outnumber 1-A-O’s by about four to one, most draft boards are loath to give the classification. Some refuse to give 1-O’s at all, even to bona fide members of pacifist religions; the feeling is that anyone taking such a stand is either a coward or a traitor. The conscientious objector’s only recourse then is to appeal. Appeals can be expensive, and those who do not have the money often become draft dodgers even though they are anxious and willing to fulfill their obligation by doing legitimate “alternative service.” An official of the American Friends Service Committee remarks that a large proportion of draft evasion is precipitated by “senile, bumbling, bigoted draft-board members.”

When Robert Whitford, a young Quaker of Madison, Wisconsin, received his 1-O classification, his draft board asked him to list three choices of work assignments. If these were not satisfactory, the draft board itself would make an assignment. They accepted Whitford’s first choice, however. Because of his knowledge of Spanish, he wanted to work with Casa Central, a social-service agency for the Spanish-speaking poor of Chicago. “I’m lucky,” he said. “Most draft boards will approve nothing but bedpan handling in hospitals.” Whitford gets $400 a month for running an “outpost” for Casa Central in a Cuban-Puerto Rican neighborhood. “Many of my friends in the resistance think that I’m copping out. They say I should have gone to jail. Why is going to jail better than doing something constructive for society?”

As Whitford’s comment suggests, the war resisters are often in conflict with each other. The 1-O’s consider the 1-A-O’s to be “cop outs,” and the resistance people, those who are awaiting jail sentences, feel similarly about the 1-O’s. All three groups revile the Underground and the refugees in Canada as lacking courage and “thinking only of themselves instead of the issues.” The resisters who follow Gandhi’s teachings believe that the only workable program is to fill the jails with sincere, educated, nonviolent war resisters who peacefully turn in their draft cards — until troubled public opinion forces the Government to change its policies. They complain that the Government is not cooperating. One resistance youth told me, “The Justice Department could arrest and convict two thousand of us tomorrow, but they’re waiting until after the 1968 elections, so the people don’t know how many of us there are.” Assistant Attorney General Fred Vinson Jr. calls this nonsense. He says, “We’re prosecuting these cases to the full extent of the law — but it takes time if we’re going to give these men the full protection of the law.” Some judges give light sentences or probation to convicted draft violators; others throw the book at them with up to 10 years in jail. A federal judge in Georgia recently meted out two consecutive five-year sentences to Clifton Haywood, the heaviest penalty given to a Selective Service violator since World War I.

There is no question that resistance is spreading — especially among the more highly educated. Jeremy Mott, a Harvard student from Ridgewood, New Jersey, was safely at work in a Church of the Brethren hospital as a 1-O, when he burned his draft card publicly in New York and helped found the group called Chicago Area Draft Resisters. He is now awaiting his arrest and jail sentence.

David McCarroll, who has degrees from Princeton and the University of Virginia, is in medical training as a 1-A-O at Fort Sam Houston. In the presence of his commanding officer he told me, “I’m totally against the war in Vietnam, and if I’m sent there I’ll have to make up my mind about going to prison instead.”

Even some of the runaways to Canada are returning to the United States in order to make a less comfortable, more forceful protest. When I interviewed 25-year-old Tom Zimmerman of Pittsburg, Kansas, he was teaching in a Toronto high school and seemed happy in his life of exile. But on December 5 he appeared in the U.S. Attorney’s office in Kansas City. He could get up to five years in prison for draft evasion, but he probably will not be prosecuted for international flight to avoid federal prosecution (an additional 10 years), because he returned voluntarily. “I felt impotent in Canada,” Zimmerman says. “Being up there just created tension for me, because all of us in Toronto were out of the mainstream of protest. I want to preserve my conscience, so I am ready to go to prison.”

As a Justice Department official told me, “I know most Americans wouldn’t agree, and certainly the fighting men in Vietnam don’t think so, but these boys, some of our brightest young men, represent the agony of our age.”

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

It worked the other way as well. My draft board in the late 1960’s in Allentown, Pa threw out the legal deferment papers of young men under its jurisdiction. I was illegally drafted twice because the draft board threw out my deferment papers. After the first time I sent in my papers registered mail so the second time was reversed a lot quicker than the first time. The first time it happened I had passed the physical and was one week from shipping out. I know two others who went through similar problems with this draft board.