Logophile: So Much to Love

The word logophile stems from the Greek roots logos “words” and philein “to love” — a logophile is someone who loves words. But there are so many things in this world to love! Can you match up these other –philes with the objects of their affection?

Match the Word with the Thing Loved

-

- An anthophile loves …

- An ailurophile really appreciates …

- A chionophile is keen on …

- A cinephile quite enjoys …

- A cynophile just adores …

- An oenophile can’t get enough of …

- A pogonophile treasures …

- A selachophile is enchanted by …

- A selenophile prizes …

-

- beards

- cats

- dogs

- flowers

- the moon

- movies

- sharks

- snow

- wine

Answers

- d

- b

- h

- f

- c

- i

- a

- g

- e

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

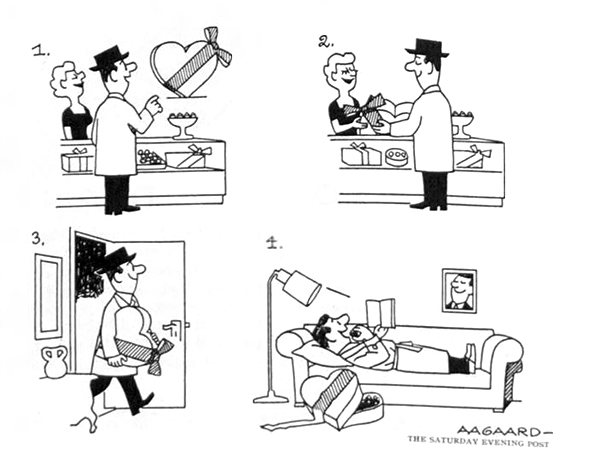

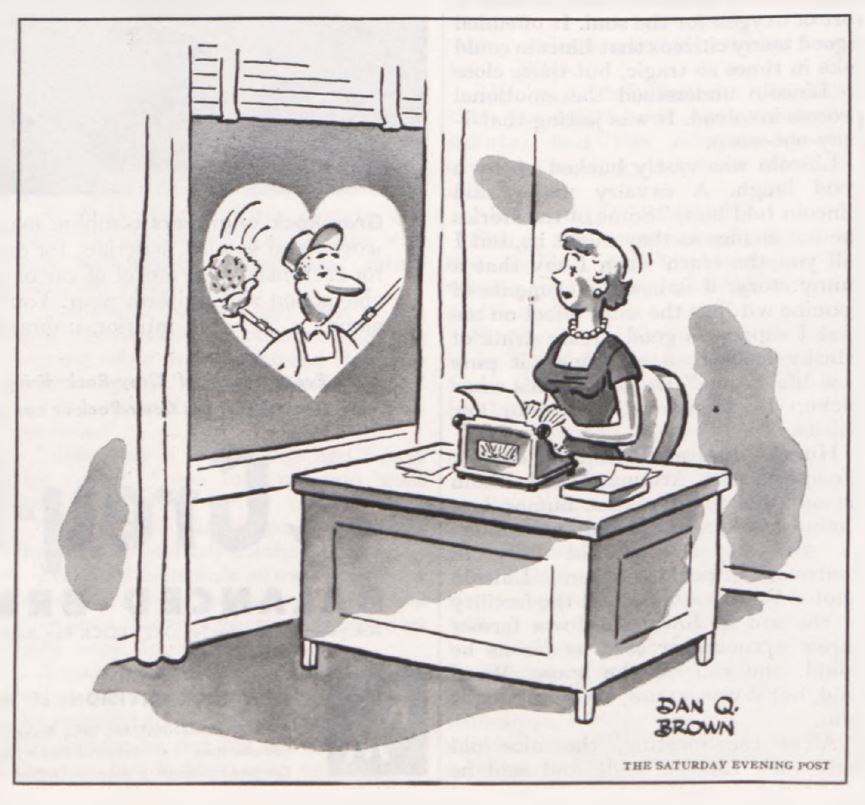

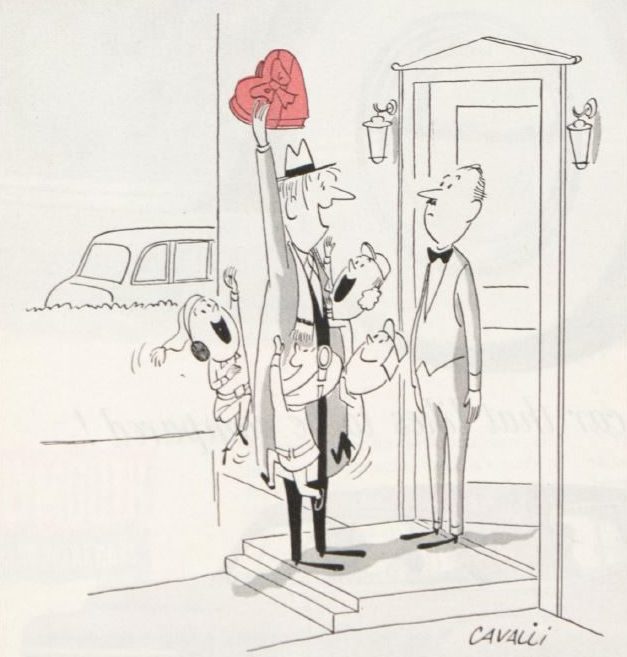

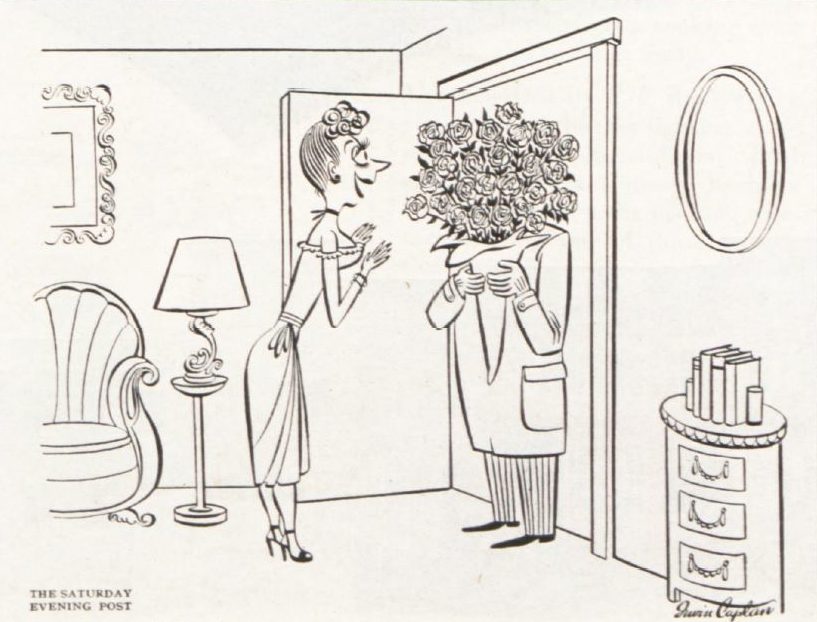

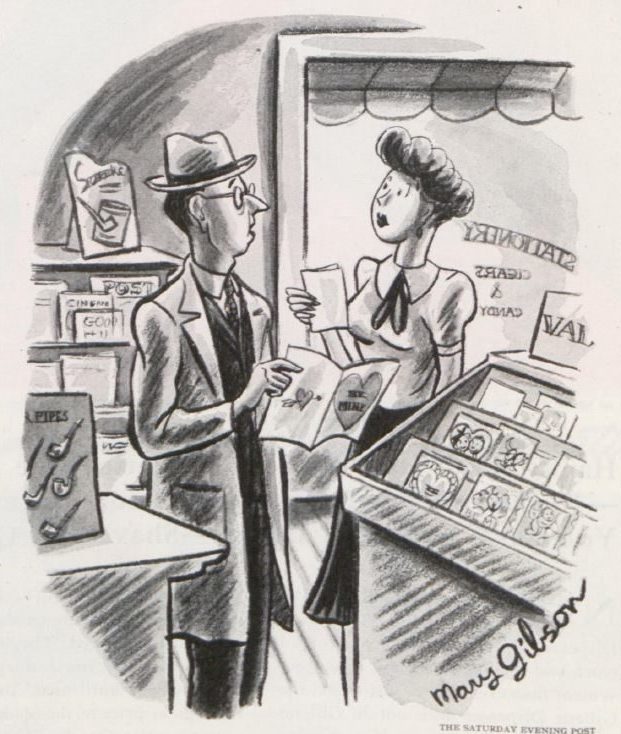

Cartoons: Be My Valentine

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

February 23, 1960

Al Piane

February 13, 1965

February 13, 1954

Taber

February 9, 1963

Bob Schroeter

February 9, 1957

Dan Q. Brown

February 13, 1954

Mort Gerberg

February 11, 1967

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Wit’s End: My Punny Valentine

Thirteen years ago this February, my first child was born. In a postpartum sentimental haze, I called him my Valentine’s baby.

Now he is almost a teenager and not quite as cherubic as before. Everyone knows that older kids develop questionable habits, exploring paths that you tried to warn them about, to no avail. They must discover for themselves that certain things — however tempting! — must never be done to excess.

I am speaking, of course, of puns.

Known as the “lowest form of humor,” they are an irresistible draw for seventh graders, who seize upon the chance to be funny and annoying at the same time. Until this year, I thought my son had a sophisticated sense of humor. His dry remarks reflected well on me, I believed. His zany witticisms showed that he came from a creative home!

But that all changed with his class presentation on the religions of Japan, which he proudly described as a pun-heavy monologue called “Tao’s It Going?”

Spurred by the success of this gambit, which made his friends laugh and did not appreciably lower his grade, he started making puns all the time, no better (I’m sorry to say) than “Tao’s it going?”

Some were so ham-handed that I began to doubt he knew what a pun was. The dictionary explains that it is “the use of a word in such a way as to suggest two or more of its meanings or the meaning of another word similar in sound.” But sometimes he would point to my burgundy coat and say, ridiculously, “Are you red-dy to go? Get it? Red-dy?”

“Stop that right now,” I’d snap like Mary Poppins. “What’s the matter with you?”

But the puns, or attempted puns, kept coming.

When we were alone in the car, I tried to impart some knowledge about the responsible use of wordplay. “Sole Desire,” I pointed out, passing a downtown shoe store. “See? That’s a pun. Sole as in shoe, and sole as in only. A lot of businesses have puns for names. A coffee shop named Higher Grounds would be another example.”

After a moment, he piped up: “A Taste of Thigh.”

“What?”

“That place right there. That’s a pun, right?”

“It’s A Taste of Thai! No one would call a restaurant A Taste of Thigh.”

“What if they served, like, pig thighs? Do pigs even have thighs?”

“I don’t know, and I’m not going to think about it.”

He picked up my phone and Googled do pigs have thighs. “They do,” he reported. And around that time, I gave up.

Believe it or not, puns were once considered the mark of the smart set. A good one-quarter of Shakespeare is ribald puns, only one of which I will repeat here. In Romeo and Juliet, one character dies uttering the pun, “Ask for me tomorrow and you shall find me a grave man,” unable to stop making lame jokes because he is bleeding out and probably delirious.

In the Jazz Age, Dorothy Parker was queen of the acerbic pun, like “You can lead a horticulture, but you can’t make her think.” And here’s Oscar Wilde, making fun of a dead German philosopher: “Immanuel doesn’t pun; he Kant.”

In fact, there is something distinctly middle-schoolish about puns, often employed to insult someone, tell racy jokes, or both. Even innocent puns have a disruptive quality: little rebellions against the staid, ordinary use of language.

In Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll’s looking-glass world is full of puns. In “The Mock Turtle’s Story,” for example, the main character explains to Alice:

“When we were little, . . . we went to school in the sea. The master was an old Turtle — we used to call him Tortoise —”

“Why did you call him Tortoise, if he wasn’t one?” Alice asked.

“We called him Tortoise because he taught us,” said the Mock Turtle angrily: “Really you are very dull!”

. . .

“And how many hours a day did you do lessons?” said Alice, in a hurry to change the subject.

“Ten hours the first day,” said the Mock Turtle: “nine the next, and so on.”

“What a curious plan!” exclaimed Alice.

“That’s the reason they’re called lessons,” the Gryphon remarked: “because they lessen from day to day.”

A school report called “Tao’s It Going?” wouldn’t raise an eyebrow in this crowd. (The Tortoise presumably would give it an A.)

No wonder, then, that some middle schoolers have shown a knack for the form. Today’s most familiar pun, often attributed to Mark Twain, was actually coined by eighth grader Florence Kerns. In 1931, Kerns entered a wordplay contest that asked her to use the word denial in a sentence. “Denial river runs through Egypt,” she wrote waggishly, creating the ur-text of the modern version: “Denial ain’t just a river in Egypt.”

In 1934, 14-year-old Margaret Walko placed in a newspaper competition with this gem: “‘Harmony’ times must I tell you to sit down?”

Not to be outdone, in the same contest, 13-year-old Helen Holodak came up with: “Will you ‘wholesome’ of these books for me?”

I know just how their mothers felt.

But in our family’s case, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. I can have a needling sense of humor with my son, discussing the Star Wars film The Force Awakens in a Scottish accent (“The Farce Aweekens”) or spontaneously breaking into song (“Mom, please!”). These annoying jokes get him to look up from whatever he’s doing and pay attention to me for a second, reminding him that, even though he’s almost 13, I’m still here. And maybe his silly puns or not-quite-puns around the kitchen do the same.

Though he’s now taller than me, he’ll always be my Valentine’s baby. And come to think of it, he’s kind of a card.

Featured image: freya-photographer / Shutterstock

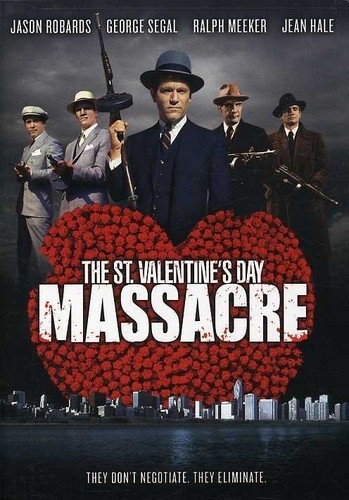

5 Things You Didn’t Know About the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre

February 14th. It’s a day for cards, flowers, and gangland slayings; at least it was on 1929, when five members of Chicago’s North Side Gang and two affiliates were gunned down in a garage in the Lincoln Park neighborhood. The man at the center of it all, as he was in many things in Chicago at that time, was Al Capone, even though the actual triggermen have never been identified to a certainty. Though the act lives on in various films and as a reference in popular culture, the actual whos and whys have largely been forgotten by the public. Here then are five things you may not know about the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

1. What Happened at the Scene?

This much is certain. It was 10:30 am, a Thursday, at the garage on 2122 North Clark Street. Witnesses saw two men dressed as police officers and two other men wearing suits, hats, and overcoats, leaving immediately after the shooting; the “police” held their guns on the other two and marched them away. Minutes later, the actual police arrived. Six men were dead and one, Frank Gusenberg, was mortally wounded, having taken 14 bullets. Yes, 14. Remarkably, he was still conscious but refused to cooperate, even going so far as to say, “No one shot me.” Frank Gusenberg died just a few hours later.

The rest of the victims included: Gusenberg’s brother, Peter; Albert Kachellek, who also went by the name James Clark; Albert Weinshank; Adam Heyer; Reinhardt Schwimmer; and John May. May’s dog, Highball, was also present, but unharmed. Other witnesses outside had seen the “police” and the other two men arrive; the “police” carried Thompson submachine guns and the other two men had shotguns. From what the police discovered inside, the group of four lined the victims up against the wall of the garage and fired repeatedly, even after the men were down.

2. Who Were the Victims?

All seven men worked either directly or indirectly for George “Bugs” Moran. Moran led the North Side Gang, an Irish-American criminal organization, and a major rival to the operations of gangster Al Capone. Kachellek/Clark was Moran’s brother-in-law and right-hand man. Brothers Peter and Frank Gusenberg worked as “muscle” or “enforcers” for Moran. Heyer served as the gang’s business manager and bookkeeper. Weinshank managed businesses that were used as fronts for Moran’s operations. Schwimmer was an associate of the gangsters, a former optician and inveterate gambler. May, an auto mechanic, sometimes did work for Moran’s people.

Over time, it was discovered that men were lured to the warehouse with the promise of obtaining a shipment of Canadian whiskey that had been stolen from Capone. Capone’s associates laid the trap, expecting Moran himself to arrive. However, Weinshank bore a strong resemblance to Moran, and it’s believed that the gunmen went ahead and acted, thinking that they actually had Moran already.

3. What Was the Motive?

Capone’s outfit had clashed with the North Side Gang for years. Since 1924, a number of previous leaders of the North Siders had been killed by men working for Capone or his predecessor in the Chicago Outfit, Johnny Torrio. Their enmity arose from issues stemming from territories, control of various criminal practices in the city, and the general ethnic conflict born from the North Siders being predominantly Irish and the Outfit’s deep Italian background. The immediate flashpoint for the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre came from the battle over running liquor in Prohibition-era Chicago, which included Moran men hijacking Capone shipments, as well as Moran’s encroachment on Capone’s dog track and saloon revenues.

4. What Was the Fallout?

The Massacre all but broke the back of the North Side Gang. While it would continue to exist, its power and influence was greatly diminished. Capone’s reach only grew, but the Massacre prompted an outcry from the citizens and greater concern from all levels of law enforcement. While many people were implicated in the crime, no one was ever convicted, and most of the people possibly connected with the actions would be murdered themselves.

The United States government began to get involved, with an IRS investigation into Capone and the eventual dispatch of Bureau of Prohibition agent Eliot Ness to the city. Ness formed his famous “Untouchables,” a group of agents known for their refusal to take bribes. The combined efforts of Ness and the other investigations would cost Capone millions and eventually see him convicted on five counts of tax evasion in 1931. Capone served seven years in prison; he was paroled in 1939, but suffered the rest of his life from neurosyphilis and paresis (paralytic dementia) before dying of a stroke in 1947.

5. Why Is It Remembered?

It’s hard to say why the Massacre casts such a long shadow. Certainly, the association with the holiday is something that cemented it in the minds of the public. The connection with Al Capone, famous in his own right, increases its mystique. And it’s certainly a key event in the much-mythologized Prohibition Era of Chicago. Much like the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, the Massacre has been the subject of many book and film adaptations, either in direct adaptations like the 1959 film Al Capone, the 1967 film The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, or as an off-screen, background event as in 1987’s The Untouchables with Kevin Costner as Ness and Robert DeNiro as Capone. The Massacre has also become an unlikely staple of comedic references, perhaps most famously in the 1959 comedy Some Like It Hot, which implies that Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis go on the run because they witnessed the Massacre.

Feature Image: Chicago in 1924, with the New Union Station in foreground. (Chicago Architectural Photographing Company; Wikimedia Commons via Public Domain)

What Should I Write in My Valentine’s Day Card?

Roses are red, but violets aren’t blue, and if you use this erroneous cliché in a card to your sweetheart they might just dump you.

Is your holiday missive missing something? You needn’t be a brilliant bard to impress your Valentine with some heartfelt verse. Steal it from us instead! Here are some clever and romantic quotations taken straight from obscurity to grace your letter to your beloved.

“Said a Lover” by Katharine Scott (July 12, 1930)

I envy him Love first did give

The idea for the adjective,

Who first did find for passioned state

The barren noun inadequate,

And, leaning to his mistress’ ear,

Made the small words of “sweet” and “dear.”

If I had lived when Love was young,

Before a thousand years of song

Made “lovely” worn and tarnished stand,

And “beautiful” so secondhand;

When “fair” was fresh, and “charming” new,

Perhaps I should have words for you!

From “Song of a Contented Heart” by Dorothy Parker (February 24, 1923)

All sullen blares the wintry blast;

Beneath gray ice the waters sleep.

Thick are the dizzying flakes and fast;

The edged air cuts cruel deep.

The stricken trees gaunt limbs extend

Like whining beggars, shrill with woe;

The cynic heavens do but send,

In bitter answer, darts of snow.

Stark lies the earth, in misery,

Beneath grim winter’s dreaded spell—

But I have you, and you have me,

So what the hell, love, what the hell!

“Any Lover to His Love” by Mary Dixon Thayer (June 13, 1925)

Where you have been the lilies blow

More thickly, and the grass is sweet

Where you have touched it with your feet.

Where you have been, and where you go

The world is fair — so fair!

Your laughter trembles in the air.

Where you have been I wander, and

The lilies and the grass

Utter your beauty as I pass.

Even the blind clouds understand

What loveliness by all is seen

Who walk where you are, or have been.

“Juliet on the Balcony” by Howard Glyndon (January 12, 1878)

O lips that are so lonely

For want of his caress;

O heart that art too faithful

To ever love hint less;

O eyes that find no sweetness

For hunger of his face;

O hands that long to feel him

Always, in every place.

My spirit leans and listens,

But only hears his name,

And thought to thought leaps onward

As flame leaps unto flame;

And all kin to each other

As any brood of flowers,

Or these sweet winds of night, love.

That fan the fainting hours!

My spirit leans and listens,

My heart stands up and cries,

And only one sweet vision

Comes ever to my eyes.

So near and yet so far love,

So dear yet out of reach,

So like some distant star, love,

Unnamed in human speech!

My spirit leans and listens,

My heart goes out to him,

Through all the long night watches,

Until the dawning dim;

My spirit leans and listens,

What if, across the night

His strong heart send a message

To flood me with delight?

“A Question of Terminology” by Robert Zacks (February 16, 1946)

How absurd a heart can be!

When it’s bound, it feels most free.

When it’s free, it wanders round

Seeking, so it can be bound.

All this simply means to me

Words do not say as they sound;

Freedom’s not till love is found.

From “Love Song” by Charles Gavan Duffy (June 21, 1856)

The face of my Love has the changeful light

That gladdens the sparkling sky of spring;

The voice of my Love is a strange delight,

As when birds in the May-time sing.

Oh, hope of my heart! Oh, light of my life!

Oh, come to me, darling, with peace and rest!

Oh, come like the summer my own sweet wife,

To your home in my longing breast!

“The Sum Total” by Patience Eden (November 15, 1930)

In casting up some old accounts

Of psychological amounts,

I find, my dear, you have a way

Of being far more good than gay:

And when I think you’re most alive,

You’re merely bland instead of blithe,

You have a cool and classic mind,

Less brave than bright, more keen than kind;

The values of your character

Merge in a grand, majestic blur

Of awesome traits — and yet, my dear,

It’s what you’re NOT which seems most clear.

“Contentment” by Philip I. Blakesly (March 16, 1940)

When an ocean is least,

Or a world or a star,

Who cares what is most?

When the cup is full,

When the heart overflows,

There is only that —

There can be no more.

And a cup will suffice for a grander measure;

When the mind’s at rest, what more is a treasure?

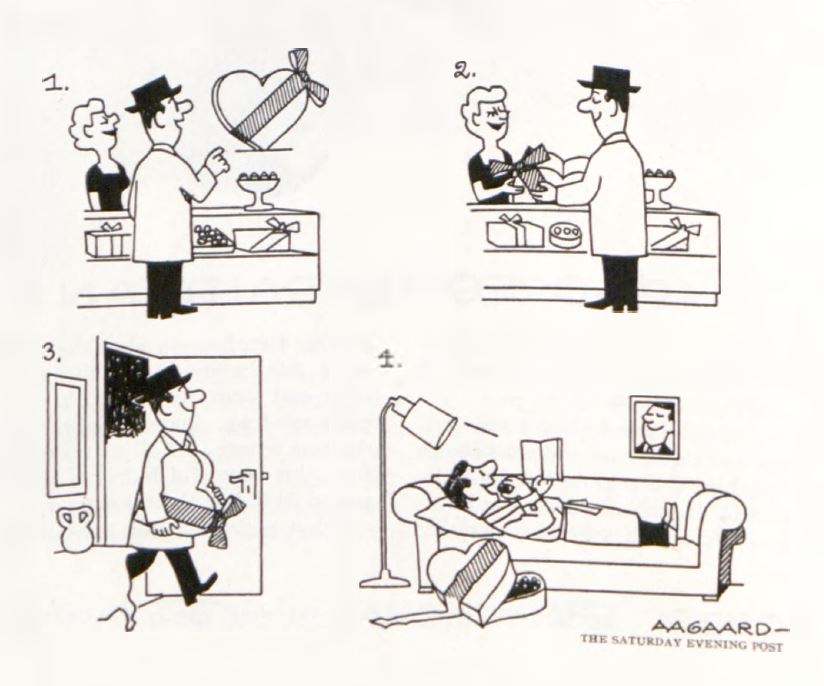

Cartoons: Be My Valentine

February 13, 1960

February 13, 1954

Dick Cavalli

February 11, 1950

Irwin Caplan

February 14, 1948

Mary Gibson

February 14, 1948

Mary Gibson

February 15, 1947

February 13, 1960

Ned Hilton

February 13, 1937

Roy Fox

February 13, 1960

This Valentine’s Day Write Love Letters to Your Friends

Have you ever sat eagerly at a desk, pen in hand, to scrawl an epically heartfelt love letter to your dearest, only to find you have disappointingly little to say? The stakes are high, and the pressure is on to put your deepest affections on paper, but somehow it all seems hokey and inadequate.

It’s safe to say that Charles Dickens, a writer whose work numbers in the tens of thousands of pages, did not have this problem. At least, he did not experience difficulty writing lengthy, expressive letters to his friends. His longtime wife, Catherine, received comparatively practical correspondence around the time that he was composing toothsome letters to acquaintances with hopes of bringing them together.

This magazine published a batch of Dickens’s letters in 1901, “The Platonic Love Letters of Charles Dickens,” that showed “Dickens in a new and in an altogether delightful character — that of the man who, though his own love troubles took an early place in his life, was able to throw himself into the fortunes of his friends with an abandonment that is unique.”

The Post did not disclose the identities of the man and woman to whom Dickens wrote in 1844 because one of them was still alive at the time. The couple was Thomas James Thompson and Christiana Jane Weller (who died in 1910). As he describes in his letter, Dickens saw Weller perform as a pianist in Liverpool and was immediately enraptured by her beauty. It would be a difficult task to find any of the author’s writing about his own wife that compares to his gushing praise of Weller in his letters to Thompson (“I would answer it to myself if any world’s breath whispered me that I had known her but a few days, that hours of hers are years in the lives of common women”).

While the letters of legendary authors remind us of their uncommon talent for using the English language, they can also serve as templates for our own communication. Even if you can’t string together complex, wordy images like Dickens, you can still write to your acquaintances in the longform, and the prose that transpires could surprise you. Without the pressure to live up to a romantic ideal, platonic letters can focus on a different kind of love. Friendship, while perhaps less urgent than romance, is as lasting and deep. To start, take a (literal) line from Dickens, and use his post script: “P.S. I don’t seem to have said half enough.”

Charles Dickens to Thomas James Thompson:

Devonshire Terrace.

Thirteenth March, 1844.

My dear — : ‘Think of Italy!’ Don’t give that up! Why, my house is entered at Phillips’s and at Gillows’, to be let for twelve months; my letter of credit lies ready at Coutts’s; my last number of Chuzzlewit comes out in June; and the first week (if not the first day) in July sees me — God willing — steaming off toward the sun.

Yes. We must have a few books—and everything that is idle, sauntering and enjoyable. We must lie down in the bottom of those boats, and devise all kinds of engines for improving on that gallant holiday. I see myself in a striped shirt, moustache, blouse, red sash, straw hat, and white trousers, sitting astride a mule, and not caring for the clock. the day of the month, or the day of the week. Tinkling bells upon the mule, I hope? I look forward to it, day and night ; and wish the time were coming. Don’t you give it up. That’s all.

I feel what you say in respect of your old suffering, and quite understood it as being expressed in your former letter. No man can enter on such lists with one who has trodden them, if he only know them in imagination.

At the father, I snap my fingers. I would leap over the head of the tallest father in Europe, if his daughter’s heart lay on the other side, and were worth having.

As to my chance of having it—well, I think I could make a guess about that (tessellating a great many little things together) which should not be very wide of the mark.

But I would not tarry, where I could not resolve. For aught you know, you may deal a heavier wound than you receive; and you certainly will not salve your own by keeping it open. You will crucify nothing but yourself upon that Diamond Cross—unless it be herself too.

If you come to town, I shall look to see you immediately. If you remain there, to hear from you. In either case, to go abroad with you, stay there with you, and come back with you.

Always, my dear —,

Faithfully your friend,

Charles Dickens.