First-amendment rights hit an all-time low between 1917 and 1919.

As the federal government raced to unite the country behind the war effort, it cracked down on any opposition or criticism. Congress passed the Espionage Act, which prohibited any action that would disrupt the country’s military or aid the enemy. Then it passed the Sedition Act, which outlawed any speech or writing that put the government’s war program in a negative light.

Over the next few years, more than 2,000 people would be charged with violating the new limits on free speech. One of the most famous of these was Eugene V. Debs, a union organizer and socialist.

In 1893, Debs had been president of the American Railway Union when it went on strike after the Pullman Company, maker of railway cars, cut its workers’ wages by 28%. Union members refused to handle Pullman cars or any cars attached to them. The federal government issued an injunction requiring striking workers back on the job, but Debs refused to comply. Ultimately the army was sent in to break the strike. Thirty strikers were killed and Debs was imprisoned for 30 days.

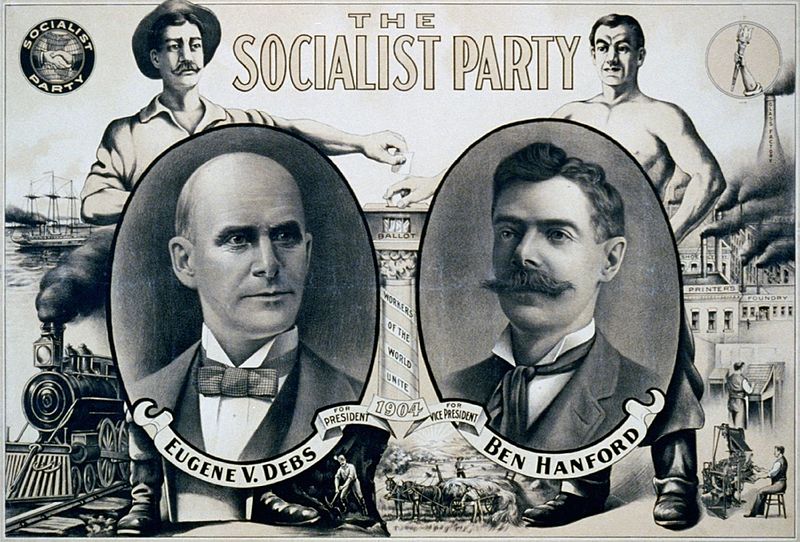

While in prison, Debs came to believe he could do more good as a socialist than a union administrator. Starting in 1900, he campaigned as the socialist candidate in five presidential elections. He never came close to winning, but he raised awareness of the disparity between rich and poor in America and earned some grudging respect from his opponents (as seen in this Post profile from 1908.)

On June 16, 1918, Debs had delivered a speech in Canton, Ohio, that caused him to be arrested and convicted under the Espionage Act. Debs appealed to the Supreme Court, but the court upheld his conviction. It believed Debs was guilty not for what he said in his Canton speech but because of a document he had previously written, “Anti-War Proclamation and Program,” as well as other comments. These showed Debs’ intention was to disrupt military preparations.

A long-time pacifist, Debs had been aware of the Espionage Act and had toned down his speech to avoid making statements that directly opposed the war effort. But Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote the court’s unanimous opinion, noted that Debs had previously said things like “the master class has always declared the war and the subject class has always fought the battles… the subject class has had nothing to gain and all to lose, including their lives; that the working class, who furnish the corpses, have never yet had a voice in declaring war and never yet had a voice in declaring peace.”

At this point in his career, Holmes had little tolerance for opposition to the government. He believed Debs represented a serious threat to democratic government and the rights of property. And urging others to disrupt the draft was no different from disrupting it themselves. He believed speech, as much as action, had the power to disrupt public order. It was in this opinion that Holmes gave his famous analogy of unfettered speech: “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man shouting fire in a theater and causing panic.”

Justifying the right to abridge the first amendment, Holmes wrote that a statement fell outside of free-speech protection if there was “a clear and present danger” it would bring about a harm that Congress has the right to prevent.

On April 13, 1919, Eugene Debs began his ten-year prison sentence. Far from being a lone, angry radical, he entered the federal prison in Oregon a sympathetic figure, jailed for objecting to a war that was now five months in the past.

In 1920, he announced his fifth run for the U.S. presidency from his jail cell and that November managed to win nearly a million votes.

Had Debs’ trial come before the Supreme Court after 1918, Justice Holmes might have argued for his acquittal. In the months following his Debs decision, he had changed his mind about the limits of free speech. He presented his ideas in his opinion on Abrams v. U.S. The case involved Russian sympathizers who urged workers to impede the manufacture of weapons for the American troops stationed in Russia. The Court upheld the Espionage Act, but Holmes dissented.

This case didn’t involve a clear a present danger, Holmes wrote. America was not officially at war. Moreover, a conviction required proof of specific intent to commit a crime — a reversal of his interpretation of Debs’ intentions.

Holmes went even further, claiming that Abrams’ ten-year sentence followed by deportation indicated he was being prosecuted not for his speech but for his beliefs.

It was here that Holmes recorded another of his memorable concepts. Free speech was essential and should be protected, he wrote, because the “marketplace of ideas” produces better thinking. Good ideas will challenge, and overturn more limited concept. Free speech leads us toward the truth.

Debs’ health began to fail in prison. In 1921, President Harding extended clemency to Debs, but did not issue a pardon. The administration still regarded him as dangerous. In a White House statement, Debs was described as “a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent.”

Yet Debs was personally invited to the White House the day after his release from jail. He was greeted cordially by President Harding, who said, “Well, I’ve heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally.”

Though Holmes distanced himself from the “clear and present danger” doctrine, the Supreme Court used it as a precedent until 1969. In that year, the court raised its protection of free speech in its Brandenburg v. Ohio decision. The government, it ruled, can only limit speech intending to produce “imminent lawless action.”

Featured image: Debs and Hanford campaign poster from 1904 (Socialist Party of America)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Eugene Debs may have been a long-time pacifist Jeff, but he didn’t take any crap from anyone and worked hard to see that the average worker didn’t get ripped off either. He clearly cared about the disparity between the rich and poor, and did all he could as an individual about it, even if it meant time in jail.

This 1908 POST profile of Eugene Debs is fascinating, from the first written word to the last. He was indeed a man of great intelligence, eloquence and magnetism. President Harding said it best near the end of your feature.

Eugene Debs was perhaps the most memorable man in American politics until Eugene McCarthy in 1968! Mr. Debs is also perhaps the most interesting historical person I’ve been introduced to in 2018 by the Post, since Fanny Fern almost 5 months ago.