Cars are like clothing. Life would go on without them, but it wouldn’t be the same. To someone like me, who has always believed that anything worth doing is worth doing to excess, it seems only right that we live in a nation with more cars than drivers. A preponderance of Americans agrees with me, which is why we as a country have carried on a 125-year love affair with the automobile. It’s been a love-hate relationship on occasion (think traffic jams, accidents, noise), but overall, it has been an enduring and fascinating one.

In the 1880s, the continental United States wasn’t even united. California, Oregon, and Nevada were states, but separated from their eastern counterparts by nine territories that would ultimately become 10 states. There were not yet cars, but the Industrial Revolution was well under way. The country had more than 160,000 miles of railroad tracks by 1890. That’s almost four times the length of today’s Interstate highway system. But if you wanted to travel where you wanted and when you wanted, you were relegated to the horse. Or the mule.

Conventional 19th century wisdom held that a man on horseback could cover about 20 miles a day without harming his mount. If you lived in rural America, you were unlikely to see much of the country that lay beyond your horse’s range in your lifetime. And such things as emergency medical service, Domino’s Pizza delivery, the Roto-Rooter Man, and the Avon Lady were not even dreams. Had they been, they still would have had to wait for the automobile. The automobile proved to be nothing less than the device that freed every American from the tyranny of geography and the loneliness of isolation.

How It All Started

The average American, if he thinks about early automotive history at all, knows that Henry Ford invented the Model T, that there was a song involving Lucille and an Oldsmobile, that tires lasted about two hours, and that you risked being considered daft if you drove a “horseless carriage.” After all, why would anyone want to swap placid old Dobbin, whose only wish was for some oats and hay a couple of times a day, for a smoke-belching, unreliable creation that not only frightened birds and little children, but also ceased working at frequent intervals? Anyone who aspired to be an early adopter of the thing was at best a person of questionable judgment and at worst deranged.

If you insist on seeing a birth certificate for the automobile, look not to American ingenuity, but the European kind. We start with German patent DRP No. 37435 issued on January 29, 1886, to Karl Benz. The generally accepted birth year, however, is 1885, the year Benz actually built his first gasoline-powered three-wheeler. All of which means that this is either the 125th or 126th anniversary of the car.

To show you that there’s nothing altogether new under the sun, what became known as the Benz Patent Motorwagen had rack-and-pinion steering and a glove compartment. But no cup holders.

We are lucky that Benz got as far as he did. His first manufacturing business failed; his second was an unwelcome association between him, a photographer, and a cheese merchant. He and his business partner Gottlieb Daimler remained in the automobile business, however, and in 1926 merged to form what became Daimler-Benz and later Daimler. More than 100,000 patents ultimately contributed to the creation of what we know as the automobile, and among the important automotive pioneers in America were the Duryea brothers. From 1893 to 1896, Charles and Frank Duryea of Chicopee, Massachusetts, built America’s first standardized and series-produced automobile, 13 of them. Alas, the brothers moved the company to Peoria, Illinois, squabbled, and ultimately went their separate ways. Frank remained in Massachusetts and, with the Stevens Arms and Tool Company, built a car called the Stevens-Duryea until 1927.

In 1900, in Europe, Ferdinand Porsche, in addition to insisting that his name be pronounced POR-shuh and not Porsche, produced a remarkable automobile. It was battery powered with four electric motors, one at each wheel. Shortly afterward, he patented the Mixte, or Mixture, which had a gasoline engine driving through a dynamo to power electric motors at the wheels. Sound familiar? It should, because it was essentially a hybrid. And it happened 111 years ago.

In Michigan, which would become the seat of the American car industry, Ransom E. Olds expanded on the Duryea brothers’ feeble run at mass production. He, not Henry Ford, established the first true assembly line and used it to build a tiller-steered car known as the “curved dash” Oldsmobile. By 1902 he was pumping 2,500 cars out the door, and this rose to 5,000 Oldsmobiles by 1904. To put these sales in perspective, Benz sold 572 vehicles in 1899.

This set the stage for Henry Ford, his refined and expanded assembly line, and the Model T. Henry Ford’s first automobile was not the Model T, but the Quadricycle, an open, gasoline-fueled, four-wheel, tiller-steered contraption with a seating capacity of two. On June 4, 1896, when he was ready to test his creation, built in a shed behind his home on Bagley Avenue in Detroit, Ford had to remove a wall because the Quadricycle would not fit through the shed’s door.

That was the bad news. The good news was that the Quadricycle worked and led to the formation of the Henry Ford Company and later the Ford Motor Company.

In 1908 Henry Ford brought out the Model T, the car that would put America on wheels. It cost $850 and sold 10,000 units its first year. Four years later, Ford reduced the price to $575. By 1916 some 55 percent of the world’s automobiles were Model Ts, a record that was never equaled. By the time Model T production ceased in 1927, more than 15 million of the cars had been sold. An astonishing number of Model Ts are still with us, and there would be more had World War II scrap drives not consumed thousands of them.

The Race Is On

Mankind being what it is, the invention of the car led almost immediately to the invention of competition, especially for the land-speed record (1911 marks the first running of the Indianapolis 500). Early land-speed record cars, like ships, were given names. And the first goal they pursued was a speed in excess of 100 kilometers per hour (62.5 mph). The first man to accomplish this was a Belgian gentleman racer named Camille Jenatzy.

Known as the Red Devil because of his beard and the ferocity of his driving style, Jenatzy drove a battery-powered electric car—La Jamais Contente, French for “The Never Satisfied.” In 1899 he drove it at the astonishing speed of more than 105 kilometers an hour (65 mph). In addition to fast driving, Jenatzy also liked fast living. In December 1913, he hosted a hunting party on his estate and drank just enough at cocktail hour to think it would be amusing to remove a bearskin rug from the parlor and use it to impersonate a bear.

Jenatzy, draped in bearskin, was crouched behind some bushes snuffling and grunting like a bear, when the editor of the Belgian Star shot and killed him. Auto executives have never quite trusted journalists since.

In 1901 the first Grand Prix race, at Pau in France, was won with an average speed of 46 miles per hour. Seventy years later, Peter Gethin won the Italian Grand Prix, averaging over 150 mph. Today, Grand Prix racers routinely top 200 mph.

Meanwhile, in Cleveland, Ohio, automaker Alexander Winton was the first to install steering wheels in cars, all previously steered by tiller-like devices. In 1901, prior to a match race against Henry Ford, Winton gave Ford the design for his steering wheel. Ford beat him. For the next 110 years, racing teams have been reluctant to share with the competition.

Cars continued to improve, but highways remained significant problems. Roads in America’s outback were awful arteries barely suited for a horse and buggy, much less for motoring. In 1912 a visionary entrepreneur, Carl Fisher, set out to change that. Fisher envisioned a cross-country gravel highway to be called the Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway. Local governments would provide labor and equipment, and the business community the materials. Motorists would be able to drive from New York to San Francisco to attend the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition.

For his cross-country road project, Fisher would attract two allies who realized what this could mean to the fledgling auto industry—Frank Seiberling, president of Goodyear, and Henry Joy, the boss at Packard. Joy suggested the project be renamed the Lincoln Highway.

As you might suppose, the project bogged down over the politics of choosing a route, but by the early 1920s, the Lincoln Highway existed and ran, at some point during its history, through 14 states.

Planning for what would become today’s Interstate Highway system began in 1938, but building it did not get under way in earnest until 1956. Today, more than 46,000 miles of interstate connect our cities. By 1972 cars were traveling Los Angeles freeways at an average speed of 60 miles an hour. By 1982, the average had dropped to 17 miles per hour. Today, discouraged experts have given up calculating freeway speeds.

The Evolution of the Modern-Day Auto

Until 1911 all cars powered by internal combustion engines were cranked by hand, an act of necessity that could break an arm. Charles Kettering introduced the electric starter on 1911 Cadillacs; now even small women and little boys could operate an automobile.

The year 1923 saw the first powered windshield washers on many cars; manual wipers were first invented by a woman in 1903. Also in 1923, a radio was offered as an option for the first time. The radio was not invented by a woman, but in 1924 alone, women inventors came up with 173 devices for automobiles.

In 1924 Walter P. Chrysler introduced the first car bearing his name at the New York Auto Show. In 1927 Ford Model A production began, and so did the sales race between Ford and Chevrolet that would last for decades.

The year 1937 saw the formal establishment of what would become Volkswagen. The so-called “People’s Car,” a pet idea of Adolf Hitler, was designed by Ferdinand Porsche and owed a great deal of its configuration to the Czech-built Tatra, a streamlined rear-engine car of the period. The People’s Car became the Kubelwagen, the German Army’s Jeep equivalent during World War II, but returned to civilian use after the war as the Volkswagen Beetle.

Buick introduced the first electric turn signals in 1938. Seventy-three years later, a surprising number of drivers have been seen using them. During the World War II years, American production switched to military vehicles and aircraft, and one of history’s most famous vehicles, the Jeep, went on sale to the government. Like the Beetle, it would become vastly popular with consumers after the war.

By the late ’40s, GM had long been operating under the leadership dictates of Alfred P. Sloan, who originated the “move-up” strategy that could take you from a Chevrolet to a Cadillac with stops along the way at Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and Buick. Unless you were a doctor, in which case you had to stop at Buick. Sloan also invented the annual model changeover, which cost stockholders and car buyers alike enough money to buy Saudi Arabia.

In 1948 Ford introduced the first F-series pickup. Today, the F-series has been the best-selling vehicle in the United States for 34 consecutive years. You still cannot see over them at a traffic light, a quality they share with the ubiquitous sport utility vehicles (SUVs). The SUV, by the way, is older than you think it is. Most automotive pundits credit Jeep with the first one, the all-metal, two-wheel-drive station wagon that appeared in 1946. If you are of the school that believes a true SUV has four-wheel drive, then the 1947 Jeep station wagon gets the nod. They sold in limited quantities.

The first tailfins, brainchild of GM styling chief Harley Earl, appeared in 1948 and set off a “mine are bigger than yours” styling war between GM and Chrysler that lasted until the early 1960s and lent true meaning to the phrase “wretched excess.”

Rolling into the Future

You know most of what happened after tailfins. Technical advancement after technical advancement came along—arguably culminating in the cup holder. We’ve seen a lot: fuel injection, remote rearview mirrors, electronic engine control, antilock brakes, and so on. A new car now costs the average consumer more than 50 percent of his or her household income (up from 33 percent in 1974), but you can’t have everything.

Cars today are better than anyone ever thought they could be. Diesels don’t rattle or smell anymore. Onboard GPS systems can help you find a hotel or a Starbucks when you’re traveling. Cars are safer and sounder—and they last for years, as do the payments.

Tires, one of the weak points in early automobile travel, now last 50,000 miles with ease. One unsung pioneer in this progress was Benjamin Franklin Goodrich who started the company bearing his name in 1880. B. F. gets credit for the first U.S.-made radial tire, the first “run flat” tire, the first synthetic rubber tire, and the first “space saver” spare. In 1988, B. F. Goodrich, as the firm was by then known, left tire-making to others and is now an aerospace company. The BFG brand is owned by Michelin.

The tailfin’s disappearance in the mid-1960s coincided almost exactly with the appearance of the Ford Mustang. Introduced in 1964 at the New York World’s Fair, the Mustang was the first affordable sporty car available to men with a midlife crisis.

Another affordable car, the Volkswagen Beetle, became a bestseller in the U.S. around this time but was anything but flashy. Almost a half-century later, the Mustang not only survives, but flourishes. The original Beetle is gone, but before it left, it managed to outsell the Model T. More than 21 million customers bought Beetles.

The 1970s saw the OPEC oil embargo, the hated 55-mph national speed limit, and automobiles so uninspired that it’s a wonder the housing industry didn’t quit building garages.

The Japanese auto industry took note, and before you could say “Banzai!” they were a major factor in the U.S. market. By the 1980s, Hondas and Toyotas were regulars on the lists of bestselling cars. A popular perception held that American automakers played golf and office politics while their Japanese counterparts worked at building better cars. That was true except for the golf part; the Japanese are obsessed with the game.

The U.S. industry produced the first minivan in 1983, and not long after, the SUV became the thing for moms and dads to drive because kids didn’t want to be seen in a minivan. The station wagon reappeared in the 1990s, but we now call it a crossover. The hybrid is back, and so is the electric car. Maybe they’ll work this time around.

The love affair between Americans and their cars has lasted for more than a century. Like most affairs of the heart, those years have produced triumph, tragedy, creativity, innovation, and a not insignificant dose of laughter and lunacy.

That is likely to continue. Certainly one hopes that the laughter and lunacy do not disappear entirely.

George Hughes

July 7, 1956

Stevan Dohanos

May 20, 1950

M. Coburn Whitmore

January 5, 1952

Eugene Iverd

January 7, 1933

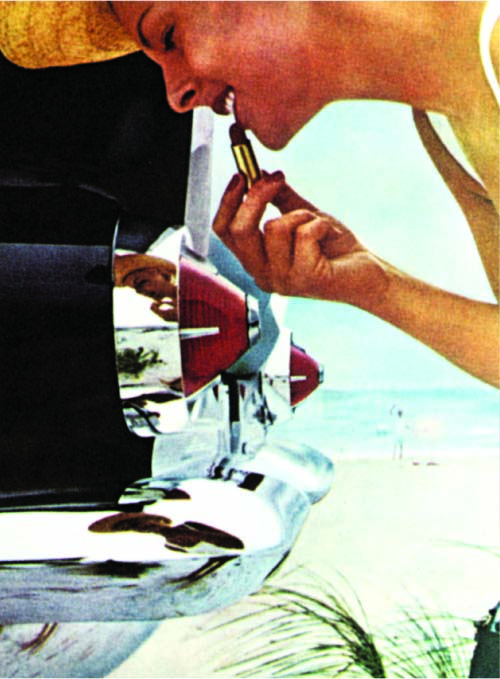

Kurt Ard

November 15, 1958

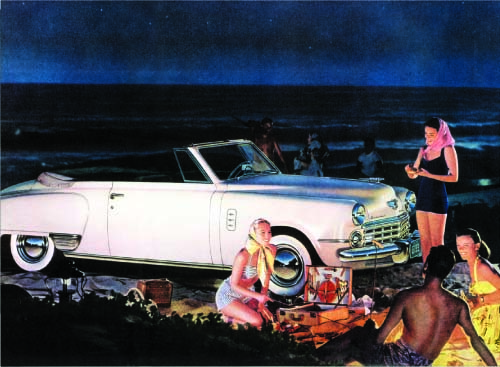

Earl Mayan

April 28, 1956

Emery Clarke

December 7 1940

Michael Dolas

December 4, 1937

William Ellis

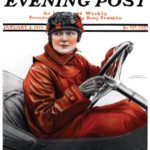

January 4, 1919

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you for an informative, amusing and positive article. I just commented on another such in the July fourth Chicago Sun-Times: Electric Cars are Right for America. I’ve been privileged to drive several battery electric cars, including racing around in a sporty red GM EV1 during a 2000 visit to Los Angeles.

Electric vehicles (EVs) certainly will work: they require very little drive-train maintenance or repair. An EV motor essentially has one moving part. Another big advantage is that electrical fuel costs less than a nickel per mile, so even the present higher prices of the EVs coming onto the market will be offset in a few years’ driving. In full mass production, EVs will be cheaper to build than their smog-mobile (internal combustion) equivalents.

EVs have other advantages: they will reduce US oil consumption by 25%, freeing us from oil tyrants and bloated corporations. We no longer must fund both sides of oil wars with our pump purchases. Air pollution will also be reduced by perhaps 20%, even including remaining electrical-generation emissions.

I must admit that the head-snapping acceleration of a well-designed and built EV is my personal favorite advantage of EVs over the Rube Goldberg vehicles that we drive today.

Breathe free,

Hugh E Webber

Electric Auto Association