Bad news may travel fast, but at the time of the Alamo siege, it rarely moved faster than the walking pace of a horse or the cruising speed of an early steamship.

So on April 9, 1836, readers must have thought the Post’s news from Texas appeared with unusual speed. A mere four weeks after the event, it reported the Mexican army was besieging the Alamo of San Antonio de Bexar and would likely obtain possession of the place.

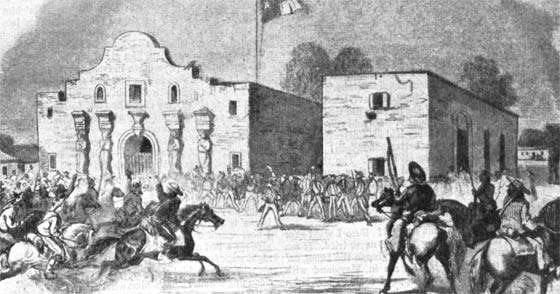

The shocking news had barely sunk in when the next issue brought a report on the fall of the Alamo and the merciless slaughter of prisoners. Under the headline “Horrible Butchery, Highly Important from Texas,” the Post reported: “… On the 6th March, about midnight, the Alamo was assaulted by the whole force of the Mexican army, commanded by [Gen. Antonio López de] Santa Anna in person. The battle was desperate until daylight, when only 7 men belonging to the Texian Garrison were found alive, who cried for quarters, but were told that there was no mercy for them—they then continued fighting until the whole were butchered.

“… Gen. [Jim] Bowie was murdered in his bed sick and helpless. [The Mexican] General Cos, on entering the fort, ordered the servant of Col. Travis to point out the body of his master. [When] he did so, Cos drew his sword and mangled the face and limbs with the malignant feeling of a Comanche savage.”

The victory was as decisive as it was brutal, but Santa Anna’s success only inspired Texans to take arms against him. Hundreds of settlers who had previously refused to support the Texan army before now rushed to offer their services.

These settlers had moved from the U.S. into the Mexican territory of Texas at the invitation of the Mexican government. The leaders in Mexico City hoped they would develop its dry northern plains and build a buffer of loyal inhabitants between themselves and the United States. Under the Mexican Constitution of 1824, the government granted the American immigrants both land and a fair degree of autonomy.

By 1830, however, Santa Anna had become Mexico’s dictator. When he dissolved the country’s legislature, several states in Mexico rose up in rebellion. Santa Anna ruthlessly put down all opposition, and then turned his attention to the northeast and the Texans who showed little inclination to recognize any government.

He decided he could waste no time or mercy suppressing the rebellion, and so marched on San Antonio with 1,800 soldiers to confront a small army of Texans encamped at the Alamo. The commander of the garrison, Col. William Travis, sent out urgent pleas for reinforcements. One of the Texan commanders he was hoping would march over the horizon to his rescue was Col. J.W. Fanning. But Fanning had troubles of his own. As the Post reported: “Distressing news has reached us of the horrible massacre and butchery of the entire command of Col. Fanning, by the tyrant monster Santa Anna and his forces. … Col. F. being overpowered by the Mexicans … capitulated upon the promise of Santa Anna, that himself and soldiers should be treated as prisoners of war. But no sooner had the fiend of hell fastened them in his clutches than he secured their arms, and early next morning ordered them all to be shot.

“The men under the immediate command of Colonel Fanning were all killed but FIVE!” (“Late and Important from Texas,” May 7, 1836).

Post readers had only two weeks to digest this news when the conflict suddenly ended with a surprising victory. On May 28, under the headline “Particulars of the Capture of Santa Anna,” the Post gave a report of the battle at San Jacinto by a Col. Hockley of the Texan army: “We commenced the attack upon them at half-past 5 o’clock, P.M. by a hot fire from our artillery.

“We marched up within 175 yards, unlimbered our pieces and gave them the grape and canister, while our brave riflemen poured in their deadly fire. In fifteen minutes the enemy were flying in every direction, and were hotly pursued by us. They left 500 of their slain behind them.

“Never was there a victory more complete. Gen. Cos was taken and killed by a pistol ball from one of our men, who instantly recognized him.”

Santa Anna was pursued by the Texans for 15 miles until his horse became bogged down near the Brazos River. Abandoning his horse, he ran for the nearby woods with his pursuers close behind. Once among the trees, his trail disappeared. As the Post described these events in an article dated May 28, “The pursuers then spread themselves, and searched the woods for a long time in vain, when it occurred to an old hunter that the [escaping officer] might have ‘taken a tree.’ The tops were then examined, when lo! the game was snugly ensconced in the forks of a large live oak.

“The captors did not know who their prisoner was until they reach the camp, when the Mexican soldiers exclaimed, ‘El General, El Jefe! Santa Anna.’”

Gen. Houston did not execute Santa Anna in reprisal for his slaughter of prisoners, but held him hostage to prevent further actions by the Mexican army.

Santa Anna’s brutality, by general opinion, was both immoral and stupid. Yet he declared he had the right to execute prisoners. Hadn’t he issued a proclamation that branded all supporters of Texan independence to be pirates? Hadn’t he flown a red flag at the Alamo? Didn’t the Texans know this meant he would take no prisoners?

He felt no mercy to foreigners who crossed his border to build their own communities, speak their own language, become prosperous, and aspire to political power.

Santa Anna was eventually returned to Mexico, where he became president again. Breaking the conditions of his release from the U.S., he marched into Texas in 1842, was again defeated, then overthrown, captured, and sent into exile in Cuba. He returned in 1846, declared himself president, was overthrown, and went into exile again. In 1853, he once more returned to Mexico and named himself dictator-for-life. Within a year, he was removed from power, and went into exile. In 1869, he died in New York while trying to raise money for an army that would return him to power.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now