Among the most memorable lines in American history, “Don’t give up the ship” is remembered because it still strikes a chord in the hearts of Americans. Yet few can recall who said it or why.

Who was Captain James Lawrence, and the why was his fear that his officers would surrender his ship, the USS Chesapeake, to the British. He uttered this phrase shortly after 6 p.m. on June 1, 1813, as he lay dying from his wounds on the floor of his cabin. Meanwhile, above decks, his crew engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with British sailors and marines who had boarded the American vessel.

Soon after, the Americans lost the Chesapeake. As Lawrence had ordered, no officer surrendered the ship. No officers were left standing to do the surrendering. The British simply took down the American flag and ran up their Union Jack. While Lawrence’s words weren’t able to save the Chesapeake, they inspired a remarkable victory. As we show, “Don’t give up the ship” inspired Commodore Oliver Perry during the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812.

Like Lawrence’s phrase, the War of 1812 might stir only vague memories when recalled today. But in the 1820s, the war was a source of great pride to many Americans, for it proved that their nation was a military match for the great British Empire.

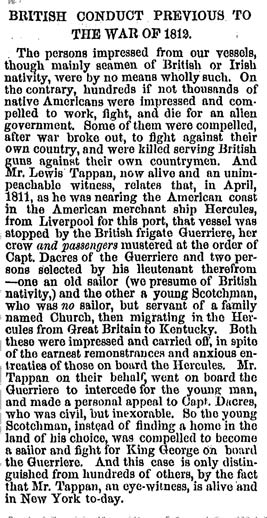

Memories of that war were revived during the Civil War when Great Britain threatened to intervene on behalf of the Confederacy and break the naval blockade of the Southern states. In January 1862, the Post printed “British Conduct Previous to the War of 1812” to remind its readers why they should still resent Great Britain 50 years after that war ended.

Back in 1812, when America declared war with Great Britain for the second time, the Royal Navy had already been fighting France for more than 15 years. It was using over 600 ships to blockade against all shipping into, and out of, French ports. To keep its ships fully crewed, the navy had resorted to seizing and ordering citizens to serve on their ships. Then, in 1807, it discovered a new source of able seamen on American merchant vessels. It began blocking our ships and taking away sailors it claimed were British subjects and putting them into service on British vessels.

The War of 1812 was only partly concerned with Britain commandeering U.S. sailors, however. The two countries were also engaged in an economic war, which was complicated by American refusal to honor the British embargo on trade with France. In addition, there were long-standing disputes between American settlers and British-supported Native Americans over land in the upper Midwest. And behind these issues was the Americans’ unstated desire to prove by arms that they deserved a place among the leading nations.

They got their proof in New Orleans when General Andrew Jackson defeated a British army. And the American Navy distinguished itself in the Battle of Lake Erie under the command of Perry.

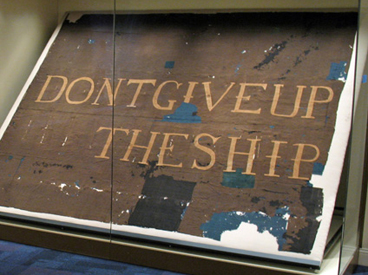

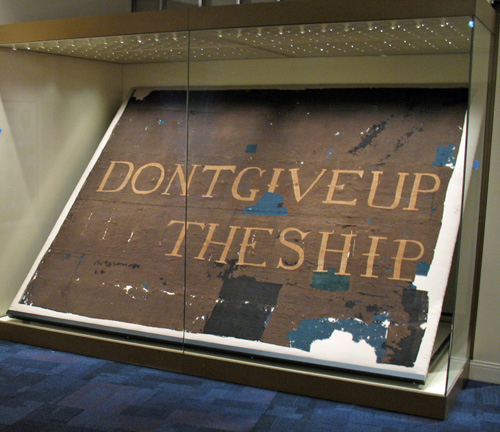

Perry had been a friend of Lawrence. After he learned of the captain’s death, Perry had made a commemorative battle flag for his command ship: a plain cloth on which the words “Dont Give Up the Ship” were attached. (Perry’s flag, as you might notice, has no apostrophe in “don’t.) On September 10, 1813, Perry hoisted this flag above his ship, the USS Lawrence, and sailed with eight other American ships to challenge six British ships for control of Lake Erie.

Perry’s Lawrence, along with the USS Niagara, headed for the two largest British ships, the HMS Detroit and Queen Charlotte. Due to unfavorable winds, the Lawrence was reduced to a slow approach, which enabled the long-range fire from the British to hit Perry’s ship long before he could strike back. By the time the Lawrence had come close enough to strike at the British ships, it had been severely damaged. More than 80 men of its 103-man crew were out of action and its guns could no longer be fired.

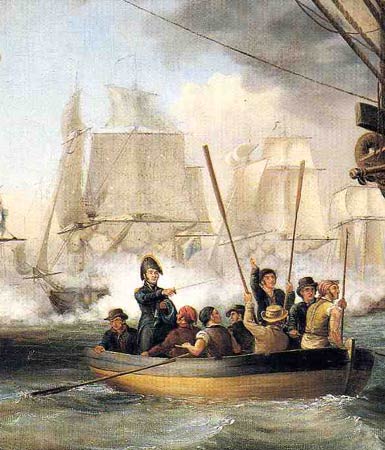

Fortunately, Perry had not been hit. He lowered his battle flag and, holding it tightly, took to the water in a lifeboat. While the British fired down at him with rifle and cannon shots, he and his crew rowed upwind to the USS Niagara, where he raised his flag, effectively moving his command to a new boat. Now, with a fresh crew and intact ship, he returned to the fight.

Soon afterward, the Detroit and Queen Charlotte became entangled while defending themselves from the Niagara’s cannon. They lost any ability to maneuver or effectively return fire. By the time they separated, they had been hit hard by the Niagara and were in no condition to continue the fight. Both captains surrendered to Perry. He promptly wrote to the American commander, “We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop.”

Out of this victory, the Americans gained control of Lake Erie, which enabled them to regain Detroit and protect Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York from British invasion.

It is interesting that the expression, “Don’t give up the ship,” remains in Americans’ memories though they may have no idea about its origin. Yet the occasion for the phrase is not as important as the spirit it captures: the instinctive, indomitable spirit, when facing anything from terrorism to tornadoes, never to give in.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now