In the October 24, 1914, issue: A former prime minister pleads his country’s case, a journalist shares his POW story, and American fashionistas cope with Parisian withdrawal.

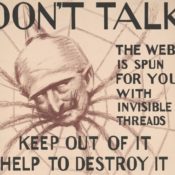

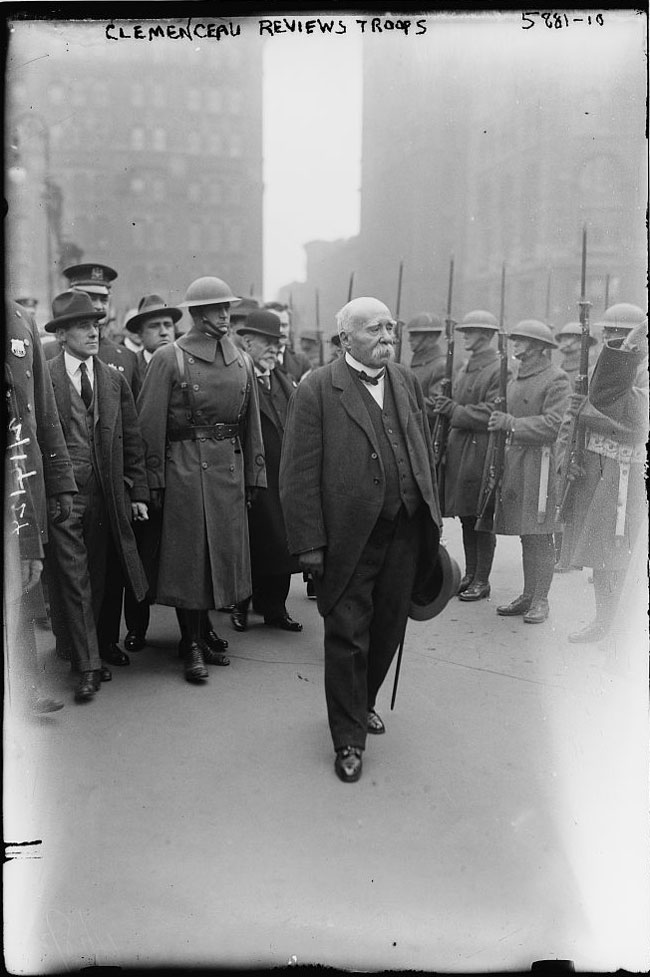

The Cause of France

By Georges Clemenceau (French Prime Minister, 1906-1909; 1917-1920)

No one was a stronger advocate of the war or a better spokesman for French hatred of Imperial Germany than Georges Clemenceau. Like Arnold Bennett in the previous week’s Post[link], he hoped to build American support for or encourage its involvement in the war.

“The great American Republic is an upright judge, before whom it is an honor to plead. … I have promised myself not to utter here a single intemperate word. Truly the bare facts speak loudly enough. What are the armies of Germany doing in Belgium? Why are they there? In the name of what cause and for what motive? For the sole reason that the strategy of the General Staff at Berlin required Belgian territory in order to invade France. There was, to be sure, a treaty of neutrality — a treaty at the bottom of which appeared the signature of the King of Prussia, written with his own hand. That treaty Wilhelm II deliberately tore up.

“In France we believe that a treaty is something which has weight, and that a nation’s signature to a treaty has a moral value which statesmen must not ignore. We did not desire war. Our intention, in the interest of the peace of Europe, was simply to continue the upbuilding of France along the noble lines of her past, within such limits as were imposed on us by the Treaty of Frankfort.

“I have cited five war-provoking attempts instituted by Germany against France. It would be impossible to cite a single instance of such an attempt on the part of France against Germany. I defy anyone to cite a single hostile act on our part!

“And now villages in Northern France are in flames; the country is ravaged — held for ransom. The inhabitants, half-crazed, are fleeing. The innocent and the harmless fall without number under the sword of massacre! Are we in the right or are we in the wrong? It passes my comprehension how the question could be asked after reading the simple statement of facts, which I have made as brief as possible.”

Crushing the People for Money

By Will Payne

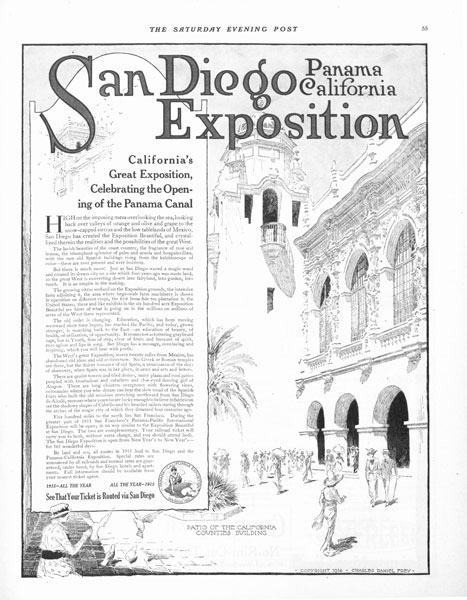

Many Americans regarded the European war only for its business opportunities. But Payne suggested American businesses look for profits in a continent much closer.

“The idea that as a result of the European war a great amount of foreign trade would fall into our lap like ripe fruit from a shaken tree has no doubt been thoroughly exploded by this time. The first effect of the war will be loss. Whatever ultimate gains we make will be a matter of time, skill, and energy.

“Europe is the great market for our exports, both raw and manufactured. … So the first fact we have to face is loss of business in our best market.

“That makes it all the more incumbent upon us to push for business in other markets, particularly in South America.

“South America buys roughly a billion dollars of foreign goods yearly, and in spite of some geographical advantage only about one-eighth comes from this country. Certainly we ought to sell more. … There is no reason why we should not, within two or three years, double our sales to South America — or, in some further years, treble them.”

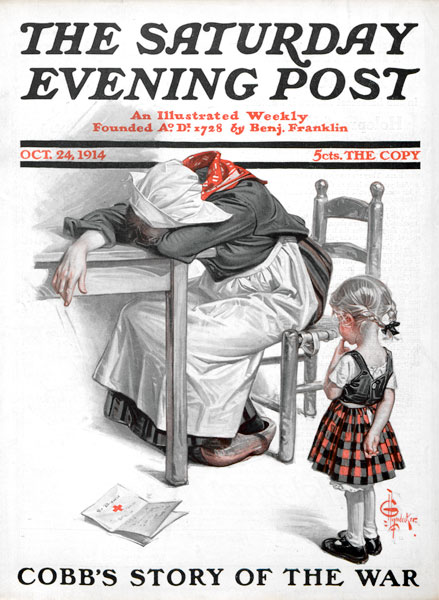

Being a Guest of the German Kaiser

By Irvin S. Cobb

Roving through Belgium to gather material for his series on the war, Cobb and his companions found themselves much farther behind German lines than they expected.

The journalists were held for several days, without food, in a large Belgian chateau. Finally, after some tense days, they were fed and told that transportation had been arranged, not to Brussels, but to the German town of Aix-la-Chapelle.

“Just as we were filing out into the dark, Sergeant Rosenthal, who was also going along, halted us and reminded us all and severally that we were not prisoners, but still guests; and that, though we were to march with the prisoners to the station, we were to go in line with the guards; and if any prisoner sought to escape it was hoped that we would aid in recapturing the runaway.

“So we promised him, each on his word of honor, that we would do this; and he insisted that we should shake hands with him as a pledge and as a token of mutual confidence, which we accordingly did. Altogether it was quite an impressive little ceremonial — and rather dramatic, I imagine.

“As he left us, however, he was heard, speaking in German, to say sotto voce to one of the guards: ‘If one of those journalists tries to slip away don’t take any chances — shoot him at once!’ It is so easy to keep one’s honor intact when you have moral support in the shape of an earnest-minded German soldier, with a gun, stepping along six feet behind you. My honor was never more intact.”

Will America Dress Herself?

By Corrine Lowe

You might recall Lowe’s article a few weeks back. She was making fun of America’s adulation of European culture. Well, she had an equal measure of scorn for American women who would wear whatever Paris told them was high fashion.

“Paris, like a circus ringmaster, has sent us through hoops and back again. She has put more American women into more clothes absolutely unsuited to them than could be counted by the most gifted mathematician. And yet, enveloped in this dense fog of the Paris superstition, many of us still cling to the belief that nobody outside of Paris can design anything more dressy than a Mother Hubbard.

“Why is it we think everything that comes out of Paris is beautiful? Why does an advertisement about the ineffable line of Paris never fail to move us? …

“With the production of more costly and beautiful fabrics Made in America, and with the demand for clothes of American design now being voiced, the designer is now … bound to lift herself out of the old restricted sphere and to show her countrywomen what she really can do.”

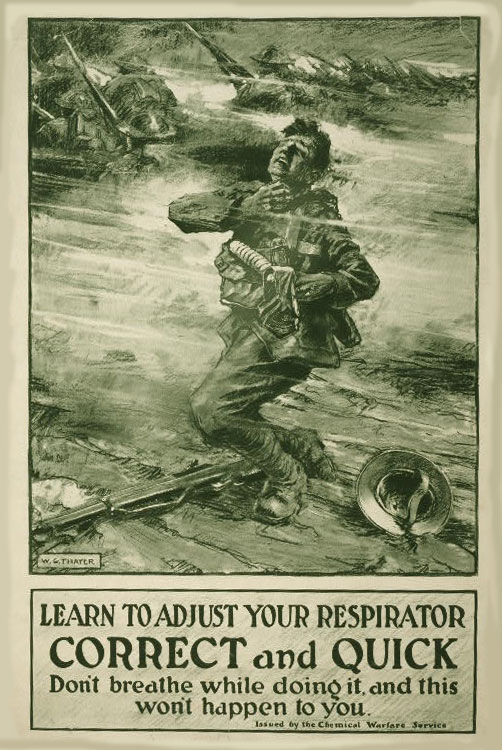

The New Warfare

By Norman Draper

The International Campaign to Ban Landmines has been trying to rid the world of antipersonnel mines, which destroy lives both during and long after wars, since 1992.

The buried explosives have been around for hundreds of years, but World War I combatants were starting to develop new applications for the concealed weapon.

“Two years ago this fall several army officers … gathered at a railroad siding outside the German city of Hannover and watched six hundred full-grown sheep driven from two cattle cars. The sheep were herded at the far end of a large field adjoining the tracks, where they were placed in an enclosure containing a little less than an acre of ground. …

“Not long after there was a puff of smoke at the center of the enclosure, and a two-foot cube of steel attached to a chain four feet long leaped out of the ground and exploded with a terrific roar. Three hundred and seventy of the sheep were dead before the army men reached the enclosure. Twenty-seven were so badly wounded they had to be shot immediately. Only nine were entirely uninjured.

“That experiment … showed the worth of its new earth bomb, which, next to the fire of the modern machine gun, is considered by many German ordnance experts to be the most effective method known of killing many men, and killing them quickly. Indeed, the earth bomb is more to be feared than the machine gun.”

“Another earth bomb known to the armies of Europe, and which is said to have been employed many times recently, is one used to destroy troop trains. This bomb, as it is generally used, is about three feet long, nine inches wide and one foot deep—just the size to allow it to be buried between railroad ties. It is filled with dynamite, and is also anchored with a chain, which usually is but eighteen inches long. Experiments conducted in Russia have shown that the bomb is more effective if exploded just after the troop train’s locomotive has passed it. Then it will blow the first car to pieces and the rest of the train will be wrecked.”

Draper concluded his short article with the per capita costs of delivering death in war.

“It costs more than $20,000 to kill a man in modern warfare . Russia spent $20,400 for every Japanese slain, and France paid $21,000 for every victim of its operations during the Franco-Prussian War. General Percin, of the French army, compiled these figures … by the simple process of dividing the total cost of the war by the number of men killed on the opposite side.

“It is estimated that, with all the modern and expensive implements employed in this war, it will cost each nation, on an average, $30,000 for every hostile soldier its own troops kill [which translates to nearly $700,000 in 2014].”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now