Early on Sunday, August 13, 1961, German guards began uncoiling barbed wire across streets in Berlin. Soon, every street leading from the eastern half of the city to the west was blocked. This was the beginning of the Berlin Wall, which would become far more formidable in coming years. The barbed wire was replaced, first by concrete blocks, then by concrete slabs 12 feet high.

When completed, the Wall was 97 miles long and surrounded West Berlin, making it an island of democratic rule inside Russian-controlled East Germany.

The Berlin Wall was, in fact, two walls, separated by an open area longer than a football field. To slow down escapers who made it over the first wall, the East German border police had installed a number of deterrents: vehicle-stopping obstacles and trenches, coiled barbed wire, guard dogs, rifle pits, bunkers, floodlights, and guard towers.

In those Cold War days, communist regimes maintained control over Eastern Europe from the Baltic to the Adriatic Seas. In that long border with the west, no area was under heavier control than Berlin. And yet East Berliners continued to escape to West Berlin.

Americans were heartened when they heard stories of escape from the Russian-controlled eastern sector. They regarded the fleeing East Berliners as heroes, not just for braving death or imprisonment for freedom, but also for disproving all the Soviet claims that life under communism was a “worker’s paradise.”

The wall wasn’t part of the Russians’ original plans for Berlin. They expected the American, British, and French armies would abandon their occupation of the German capital after World War II. When they withdrew, the Russians would assume full control of Berlin and bring it into the East German “republic.” But the armies remained in West Berlin while its citizens were rebuilding their homes, their government, and their businesses.

In those early days, Berliners were still free to move from the Russian zone in the east into the American, French, or British zones. But East Berliners noticed their neighbors to the west were enjoying greater freedom and fewer food shortages. So they began moving across town in large numbers.

Every day in June 1961, an average of 630 East Berliners moved west. In July, the daily emigration average reached 967. On August 12, the day before the barbed wire was put up, roughly 2,400 émigrés headed out of the Russian zone.

Russian Premier Nikita Khruschev had seen enough. He had to end this embarrassment and loss of manpower. That night, he ordered the East German forces under Russian control to close off traffic to the west.

But some East Berliners had already committed themselves to flee communist rule. As they watched a concrete wall replace the barbed wire, they began looking for other avenues of escape. They found buildings adjacent to the wall where they could jump from a window and land in the west. A father rigged a zip line sent his family over the wall. A driver modified a low-profile sports car so it could drive underneath the crossing gate at a checkpoint. A pilot flew a stolen light aircraft into the west.

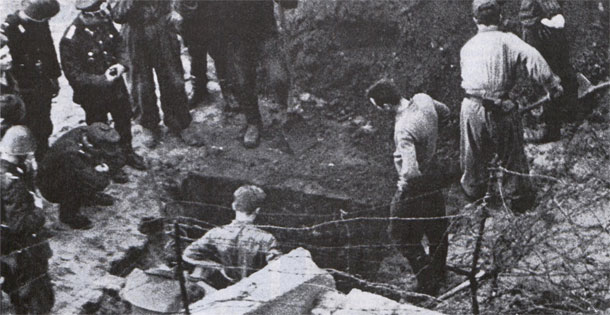

Some got out by hiding inside telephone cable spools being shipped to West Germany. Some walked through the checkpoint in homemade Russian uniforms. Some tried crashing their vehicles through checkpoints. And others tunneled.

In September 1962, a group of students dug a 400-foot tunnel 15 feet beneath street level. When finished, the tunnel would let escapees crawl to the west through a corridor less than three feet high and three feet wide. On September 14, 1962, it brought 29 people out of East Berlin, earning it the nickname Tunnel 29.

(Three of the students working on the tunnel sold NBC television the rights to film the project, which can be seen here)

The tunnel couldn’t have been built without the dedication of university students in West Berlin. They risked their lives, and possible capture by East German border guards, to help the escapees because they believed they should do something to fight oppression. One of the students told Post writer Don Cook, “Our parents did nothing about the Nazis, and we have been reproving them in silence for it for years … I’m not going to have my children asking me 15 or 20 years from now, ‘What did you do to fight Communism?’ I’m here to do something.” (Read the entire article “Digging a Way to Freedom” by Don Cook from the December 1, 1962 issue of the Post.)

While Cook honored the heroism of the diggers, planners, and escapees, he didn’t ignore the many who failed in their escape attempts. In 1962, the East German courts had already sentenced over 1,000 people who’d attempted to flee the East, and another 895 were under arrest and awaiting trial. Over 50 escapees, he added, had already been shot and killed trying to cross the Wall. Before the wall was knocked down in 1989, at least 130 people had been killed while trying to escape.

For years, West Berliners placed white crosses beside the Wall where Germans died in their attempt reach freedom. With the Wall destroyed, the crosses have now been moved to a central memorial site.

The Berlin Wall is in a thousand pieces, spread around the globe in museums and private collections. A few sections have been left standing in Berlin, monuments to a barrier that was once formidable but never impenetrable.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now