Not all Americans were personally affected by the fighting in World War II, but all had to deal with wartime shortages of consumer goods. Manufacturers were diverting more of their raw materials and manpower to filling military contracts. Production of consumer items had fallen or, in some cases, stopped.

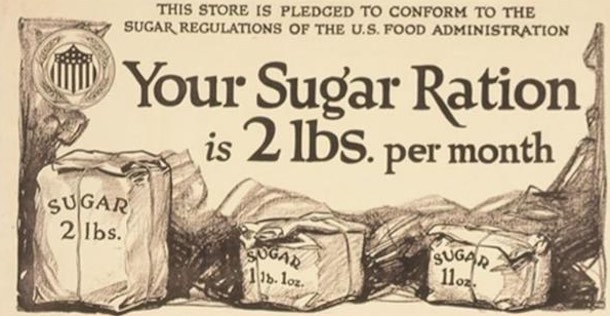

Normally, shortages drive up prices, making products unaffordable to a larger percentage of the population. In order to ensure an equal distribution of goods in limited supply, the government began rationing programs.

Just days after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Office of Price Administration (OPA) began to ration the sale of tires. America’s chief source of rubber had been lost when the Japanese seized Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. By limiting the supply of tires, the government also hoped to reduced gas consumption by motorists.

The OPA set up ration boards across the country, staffed by 7,500 volunteers, who determined who would get the rationed tires.

In January 1942, the War Production Board took a similar approach to the auto industry. It ordered an end to unregulated sales of automobiles to civilians. Ration boards would now determine who could buy any of the 500,000 new cars made before the auto industry switched completely to defense work.

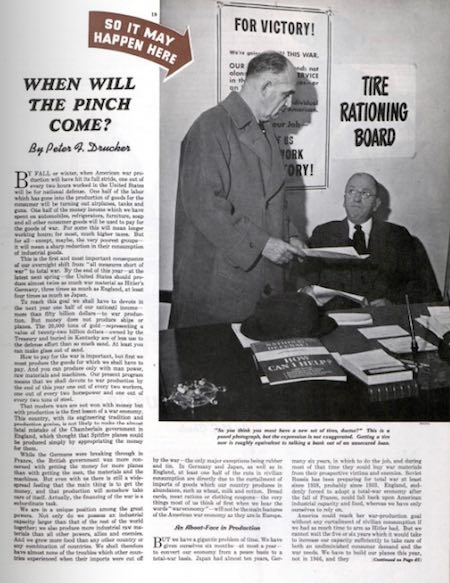

Seventy-five years ago this week, in the March 7, 1942, issue, management pioneer Peter Drucker told Post readers that sugar rationing would soon begin. In his article, “When Will the Pinch Come?” he listed several goods that wouldn’t be produced until the war was over: refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, washing machines, air conditioners, sewing machines, irons, radios, and phonographs.

His article must have raised more than few eyebrows when it was published. The real shortages, said Drucker, were just beginning. They would be significant by Christmas.

The shortage of goods must have struck many Americans as ironic. They had waited through the 1930s for a return of good wages. Now, with incomes rising and money to spend, the luxuries they’d waited to buy were unavailable.

In this knowledgeable analysis, Drucker explains how rationing and the war economy would affect business. The American economy would undergo “great and violent changes” in 1942. There would be shortages, but he didn’t anticipate real hardships. At worst, he said, the average American would “live briefly as his grandfather lived all his life.”

Featured image: National Archives

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I read this entire article, and it doesn’t pull any punches about what would have to be given up for the war effort between 1942 and ’45. It was an even greater sacrifice being only a couple of years really, after the long Depression.

Although Americans then I’m sure were unhappy, frustrated and at times hated the inconveniences the shortages/rations and the complete unavailability of some items caused, they knew it was for the greater good (the big picture) and most people were on the same page as Americans anyhow then.

If this were to happen again now, some people would cooperate, but I think there would be a real increase in all kinds of crime. Too much division in too many ways, accelerating in a stressed-out nation already very tightly wound.