The First World War, which the U.S. entered 100 years ago today, is so far in our past that it can feel like ancient history. How can we understand the U.S. of 1917 when so much has changed since then?

One way is to compare what it means to be an “average American” then and now, though we’re fairly certain that Saturday Evening Post readers are, on the whole, above average.

If you were an average American on this day in 1917, you were one of 103 million citizens. (Today’s population is over 320 million.) Being a typical 1917 American, you would be among the 86 percent of the population that was Caucasian, and you would live on a farm or in a town with a population of 2,500 or less. Because of your rural locale, you wouldn’t have heard about that new American music called “jazz” that was brewing in the big cities; it had only been recorded for the first time in March.

Suppose you were the typical woman of 1917. You’d be between the ages of 15 and 19, but you wouldn’t get married until you were 21. You had a life expectancy of 49 years (today it’s 78.8 years). You couldn’t vote, you couldn’t obtain birth control, and you had no education beyond the eighth grade. You were living in your parents’ house. You washed your hair just once a month, and you would probably deliver all three of your babies at home.

But the typical American in 1917 was a man; the majority of Americans were male until the 1950s. As an average American, adult male, you were between 20 and 24 years old with a life expectancy of 47 years.

You worked 55 hours a week for 22 cents an hour, but your income wouldn’t go as far in 1917 as it does today. For example, you would spend 33 percent of your earnings on food (compared to 16 percent today). Every year, you would consume 11.5 pounds of lard, 14 pounds of chicken (it’s over 90 pounds today), and 88 pounds of sugar (at 4 cents a pound). Also, your clothing expenses took up 13 percent of your annual income, compared to just 3 percent today. You’d need to save up almost an entire year’s income to buy the average new car, which cost around $450 (today it’s around $34,000).

However, if you were in the fortunate minority that owned one of the 4.7 million cars on America’s roads in 1917, you would pay as much as 20 cents for a gallon of gas (the equivalent of $3.81 per gallon today). And if you lived in any city, the law would prevent you from traveling faster than 10 miles per hour.

The average new home today costs $390,000. If you had bought an average new home in 1917, it would cost $5,000 (the equivalent of $95,000 in today’s dollars), and you’d share it with four other people instead of the 2.3 others you’d share it with today.

As an average American, you wouldn’t be among the fortunate 14 percent of the population whose homes had bathtubs with running water, or the 18 percent of households with at least one live-in servant. Also, you’d have no phone in your home; that was a privilege enjoyed by only 8 percent of Americans. Instead, your long-distance communication would be done by mail, though Americans sent six times more telegrams than letters.

As a typical male in 1917, you wouldn’t have graduated from high school — only 10 percent did so — but at least you could read and write (25 percent of Americans couldn’t). You would be considered ready for military service. Before the war was over, if you were between 18 and 31, you had a 25 percent chance of serving in uniform, as either a draftee or a volunteer.

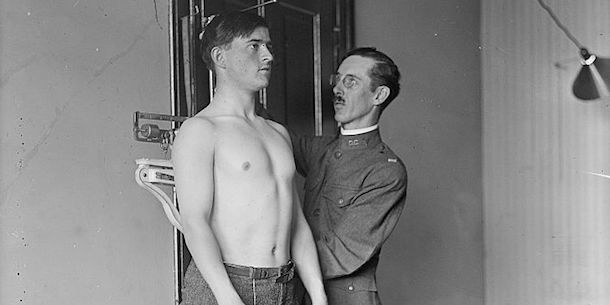

If you did end up as an average soldier in the armed forces, you would be 25 years old, 5 feet, 7½ inches tall, and a compact 144 pounds, with a 31-inch waist and 14-inch neck. Most likely, you would be among the 4 million American men who served in the American Expeditionary Forces. If so, you had a 50/50 chance of serving overseas, a 5 percent chance of being wounded in battle, and a 1.3 percent chance of being killed in the fighting. But, as a typical G.I. (a term that wouldn’t be in use until the next world war), you would not be among the 43,000 servicemen who died of influenza during and after the war.

However, when you got home in 1918 after surviving the flu epidemic and the war, you would no longer be the typical American you’d been in 1917.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is a really fascinating article that puts a lot of things in perspective. I’m more appreciative living now in certain ways than if it were 1917. In many ways 1917 and 2017 are both extremes, especially economically; it does make me think twice about complaining (quite as much) about certain things today.

Still, from what I know, the midway point of 1967 was the great compromise for most Americans, still riding the great post World War II crest of the wave. The Vietnam War and other factors took away much of the happiness of the time, including appreciation of that largely ideal economy.