Foreign travel has become so integral to the job of the U.S. president that it’s hard to believe the first 25 presidents never left the country while in office.

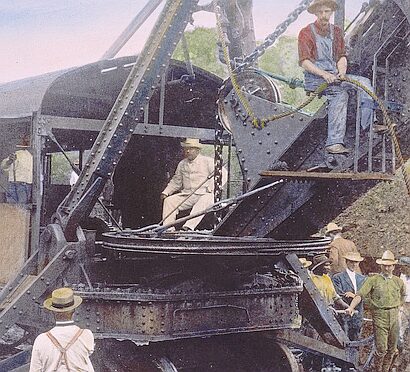

The first president to do so was Theodore Roosevelt. In November 1906, Roosevelt traveled to Panama to bring attention to the massive construction project the U.S. had undertaken to build the canal. And he didn’t mind grabbing a little press attention for himself.

After Roosevelt, every president found a reason for at least one trip abroad. President Franklin Roosevelt made the most trips. His 21 visits to foreign countries, while impressive, were spread over his 12 years as president. In just eight years, President Eisenhower took 17 trips, including one to Korea to see for himself how the war was progressing.

Scores of presidential trips have been taken and forgotten. Here are seven that made a lasting impression on history.

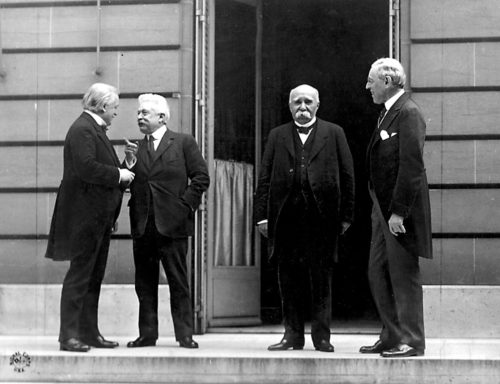

1. Woodrow Wilson — Paris and other European Capitals

December 14–February 24, 1919 and March 14 –June 18, 1919

President Wilson spent half a year abroad, immersed in the politics of Europe. He arrived in Paris intent on building a lasting peace out of the Allied victory in the First World War and brought Fourteen Points he thought would establish lasting, peaceful relations between nations — an effort that led to his winning the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize. But he was outmatched in negotiation by the cynical policies of France and Britain. Contrary to Wilson’s wishes, they dropped crushing reparation fines on Germany, which led to the next world war. And when Wilson finally returned to the States to push for Congress to accept entry into the League of Nations, Congress voted him down, beginning a new period of American isolationism.

2. Franklin D. Roosevelt — Yalta

February 3–12, 1945

Roosevelt had been the principal coordinator of Allied efforts in previous wartime conferences, but he wasn’t the star in this one. Soviet premier Joseph Stalin managed to walk away with an agreement that would put all of Eastern Europe under Soviet influence. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill expected Joseph Stalin to hold free postwar elections in the countries in this region as a prelude to Russian withdrawal, but Stalin had no intention of leaving. He also managed to enter the war with Japan in exchange for control over several areas within China. From these areas, he was able to ship arms to the communist army in China, helping ensure that they wrested leadership of the country from the Chinese Nationalists.

3. Harry Truman — Potsdam

July 16–August 2, 1945

Stepping into the role of America’s negotiator when President Roosevelt suddenly died, Truman worked with Churchill and Stalin to decide the fate of postwar Germany. The country would be divided into four zones of Allied occupation (France was the fourth occupying power). The three leaders also agreed to return refugees to their countries of origin and defined the terms the Allies would demand of Japan before accepting its surrender.

4. John F. Kennedy —Berlin

June 26, 1963

At war’s end, Berlin was divided into four zones, each controlled by a different ally. It soon became obvious that the Russians in East Berlin were only waiting for the other allies to leave before seizing the rest of the city. The fact that West Berlin was a democratic island deep in Russian-occupied East Germany left West Berliners apprehensive of being abandoned. Americans had shown their support of West Berlin by flying in tons of vital supplies when Russia blockaded the city. Yet Berliners wondered how strong America’s commitment to the city was. Then President Kennedy arrived to reassure them of continuing U.S. support, uttering the memorable lines, “All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’”

5. Richard Nixon — China

February 21–28, 1972

Relations between communist Russia and communist China had been chummy after World War II, but in the following years, the Chinese began resenting Russia’s proprietary attitude toward them. President Nixon saw this as an opportunity. He believed widening the gap between the countries would encourage Russia to put more effort in pursuing détente with the West. Meanwhile, China saw a Sino-American connection as a way to get back at Russia.

Nixon and Chinese officials worked out a bilateral agreement that would lead to America diplomatically recognizing communist China and cutting ties to its ally, Taiwan.

6. Jimmy Carter — Iran

December 31, 1977–January 1, 1978

President Carter visited the Shah and publicly complimented him for creating a stable nation within the turbulent Middle East. Iranian citizens knew better; the Shah remained in power only by the work of a security force that brutally put down all opposition. Iranians felt betrayed by Carter, who had spoked so highly of supporting human rights. When the Shah was deposed the following year, they remembered Carter’s words — and America’s refusal to hand over the Shah — as they stormed the U.S. embassy and took the staff hostage. America’s long support of the Shah is still recalled with bitterness in Iran.

7. Ronald Reagan — Geneva, Switzerland

November 19–21, 1985

President Reagan had risen in politics on his reputation for bitterly opposing communism and the Soviet regime. But in 1985, at his insistence, he met with General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev. The first meeting was contentious, and both leaders exchanged accusations over past differences. But the meeting led to four more that, in time, considerably eased East-West tensions and probably contributed to the collapse of the Soviet empire.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now