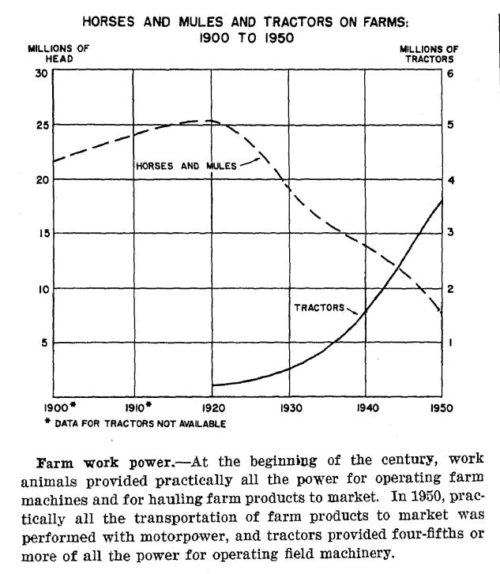

Seventy-five years ago this week, the Post article “Revolution in the Plant World” was boasting of U.S. agriculture’s “40 percent cut in labor needs” since the first World War because of advancements in farming technology and crop hybridization. Tractors were replacing work animals at a breakneck speed, and a relatively recent wheat hybrid called “Hope wheat” had virtually saved wheat agriculture in the United States.

Seventy-five years ago this week, the Post article “Revolution in the Plant World” was boasting of U.S. agriculture’s “40 percent cut in labor needs” since the first World War because of advancements in farming technology and crop hybridization. Tractors were replacing work animals at a breakneck speed, and a relatively recent wheat hybrid called “Hope wheat” had virtually saved wheat agriculture in the United States.

The Hope wheat was a hybrid between traditional wheat and Yaroslav emmer, an ancient grain also known as farro. The successful crossbreeding of the two — thought impossible by most scientists at the time — was performed by E.S. McFadden, a South Dakota farmer and student. As a child, McFadden watched a stem rust epidemic wipe out half the wheat fields in South Dakota, while the emmer crop was unaffected. His hybrid wheat was the reason for the Post’s 1942 claim that the “whole picture is changed today, and America could raise possibly 2,000,000,000 bushels of wheat without any very great effort.” Hope wheat spread across the prairies and set the stage for Norman Borlaug’s Green Revolution of the 1960s, earning the Iowa farmer a Nobel Peace Prize.

Today’s food system comes with its own challenges that were unforeseeable in 1942. Nitrogen fertilizers — necessary for hybrid high-yield variety crops — pollute the country’s waterways, and industrial agriculture threatens biodiversity. According to a 2016 report from The Guardian, we’re throwing away half of our food anyway. But, the sentiment from 75 years ago still rings true: “Maybe we have got too much new agriculture. Maybe. But a full smokehouse and granary and fruit bin are most comforting at a time when the world has gone mad.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now