If you were a magazine reader in the 1950s, you probably saw an ad promoting army surplus goods at incredibly low prices. Even if you didn’t see the ad, you might have heard rumors about surplus jeeps being sold for $50. The jeeps, someone would tell you, were in pristine condition, still packed in crates for shipment overseas, with all vital parts protected with a thick coating of grease.

Such an implausibly low price might have seemed reasonable in postwar America when the government was eager to recoup any money it could on military surplus. The magazine ad proclaimed “Hundreds of items for as little as 2¢ and 3¢ on the dollar!” It listed such items as parachutes, tents, airplanes, bicycles, and giant balloons.

Those balloons were the dirigible-shaped barrage balloons, designed to float on cables over cities to prevent dive bombers. And the government was having a hard time selling them.

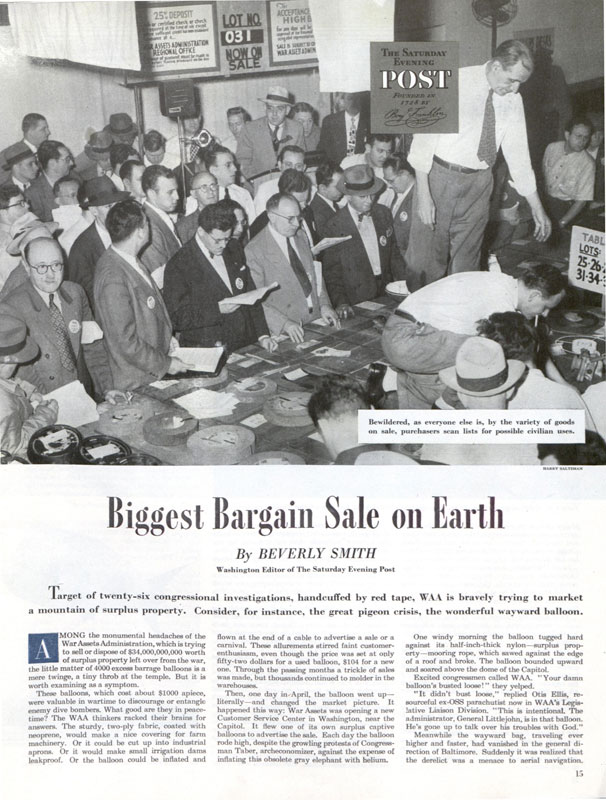

As the Post reported in its 1947 article, “The Biggest Bargain Sale on Earth,” 4,000 of these balloons were left unused when the war ended. The War Assets Administration (WAA) was charged with selling them.

To advertise their availability, the WAA inflated one of these balloon and sent it aloft over its Customer Service Center in Washington, D.C. Not a single balloon was sold until, one day, the balloon broke free and began interfering with air traffic. The story made national news, and suddenly the WAA was receiving offers from enough buyers to sell out the stock.

Then the Civil Aeronautics Board stepped in. The balloons, they said, were a hazard to aviation. They couldn’t be sold until they were rendered unflyable. And since no one knew how to do this, $4 million of barrage balloons remained in their warehouses.

The balloons were just a small part of the problem. The amount of materiel was immense. To give an idea, the author of the article, Beverly Smith, asked the reader to imagine a line of warehouses, each holding one million dollars in surplus material. If the warehouses were placed 130 yards apart, the line would reach from New York to San Francisco.

The variety of surplus material was almost unimaginable. There were thousands of miles of pipeline, entire sewage systems, two million sets of false teeth, and tens of thousands of obsolescent war planes (sold as scrap for less than a penny on the dollar).

The WAA did have some successes. They sold 150,000 rubber life rafts, recouping $3 million on an equipment that originally cost $30 million. Each raft was sold as part of a $105 package containing 143 items, which included a bible, 12 signal flares, a bilge pump, a gallon of massage oil, a checkerboard, and back issues of Fortune, Esquire, Reader’s Digest, and The Saturday Evening Post.

But among the items offered by the WAA, there were no $50 jeeps. The government had sold them after the war for $975, but all had been previously used, some of them in combat. And veterans were given first choice.

If you had responded to the magazine advertiser and mailed them the requested $1, you would have received information on how to purchase surplus materials from the General Services Administration — the same information the government provided free to anyone.

Much of America’s $34 billion in World War II surplus eventually found its way into military surplus stores across the country. For years, these businesses sold a wide variety of materiel, from uniforms to mess kits, K rations, helmets, and other non-lethal paraphernalia of war.

Many of these stores have now closed, or have begun stocking imported, non-military goods, because the nature of war has changed. Today’s military operations are limited and highly focused. America no longer outfits millions of soldiers and sailors for combat.

However, they still need transportation, and they rely on large numbers of their tactical vehicle — the General High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle or Humvee. Surplus Humvees are auctioned online by Ritchie Bros., some with odometers reading just 140 miles. Final sales prices for running Humvees range from $4,000 and $20,000.

No one’s talking about $50 Jeeps now.

Featured image: Amphibian jeeps awaiting truck transport, 1943 (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now