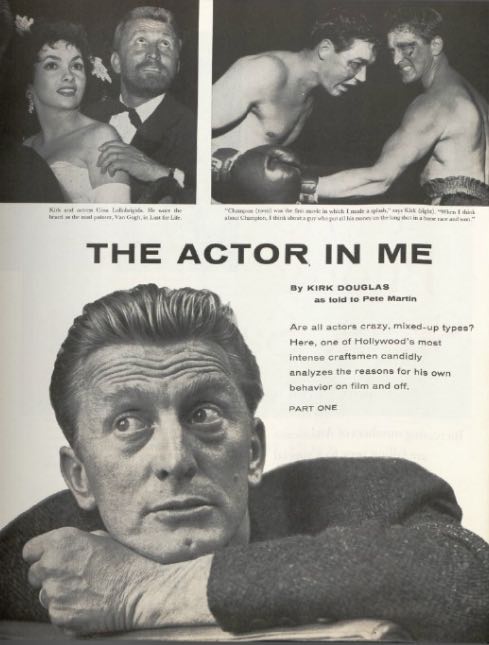

This is an abridged version of two articles written by Kirk Douglas with Pete Martin, which appeared in the in the June 22 and June 29, 1957, issues of The Saturday Evening Post. You can read the complete original article in the flipbook, below.

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood. This edition can be ordered here.

Apparently the public takes it for granted that if you’re a successful actor, you must be a schmoe. There’s nothing like scoring a hit to make people hunt for new, unpleasant traits in your character. Searching for them, they discover them whether they’re there or not. Then they say, “What did I tell you? He’s changed.”

Usually the change is in other people, not the actor. As a raw newcomer to Hollywood, I had trouble getting a table in the swankier local restaurants. Now I can get a table most of the time, although I don’t deserve it any more than I did 10 years ago. What has changed is not me but the attitude of the headwaiters toward me.

The first movie in which I made a splash was Champion. After I appeared in it, I was told by a woman columnist, “You’ve changed. Now you’re sexy.”

A writer told me: “Making a hit in Champion changed your personality. I don’t like you now.”

“I haven’t changed,” I told him. “I was an s.o.b. before I did Champion and I’m still an s.o.b., only I was too unimportant for you to notice it before.”

I think that I’m still the way I was before Champion. I didn’t kowtow to producers then; I’m not noted for it now. Even when I was a bum, standing in line on the Bowery to buy a cheap Salvation Army meal, I didn’t buddy up to people I thought were jerks, no matter how much good they could do me. This is not always the accepted way to get ahead. Too often in the entertainment field, the idea persists that you can ignore influential creeps only after you have become successful.

Nowadays when I go back to my hometown, Amsterdam, New York, everybody there takes it for granted that I must have an ego the size of a weather balloon. People in Amsterdam ask me, “Do you remember when we did so-and-so?” and when I say, “Sure, I remember,” they’re amazed.

“What do you know!” they exclaim. “Kirk remembers.”

I want to ask them, “If you remember little things that happened around you. How many people are doing what they want to do? Yet no one ever hit an actor over the head to make him become an actor. You’re an actor because that’s what you want to be, despite all the difficulties.

An actor’s need to project his emotions from his insides to his outside sandpapers his nerves. His feelings lie so close to the surface that such terms as “crazy” and “mixed up” are often applied to him.

My friend, producer-director Billy Wilder, gives me the berry for hankering to play every good role Hollywood offers. He says, “Kirk gives you all he’s got. His chest begins to heave even before a director snaps his fingers. He doesn’t need violins playing in a corner to put him in the right mood.” I hope he’s right. If he means that I enjoy acting, he is right.

There’s another thing about actors — every one of them wants to play each role he’s given better than it’s humanly possible for him to play it. I not only want to achieve perfection in each role I play, I want to play all the good roles there are to play. It’s absurd to feel this way, but it makes me unhappy that I can’t be starring in my next picture, The Viking, and playing two other top roles at the same time.

I’ll always believe that there’s value in being willing to work like a horse to do a better job. Until I played the prize fighter in Champion, I had never boxed at all. When I started work in Champion, I had three left hands, none of which could jab or throw a punch, but I trained in a gym until I became a passable fighter.

It could be that my willingness to work long and hard to master a new skill is just another manifestation of my desire to create a sensation with an unexpected accomplishment; then throw it away by saying, “It’s really nothing.” But I honestly don’t think that’s it. It’s not so much exhibitionism on my part as a need to believe in those games of “Let’s pretend.” If I believe in them hard enough, moviegoers may believe in them too.

The Truth

I’m the kind of actor I am because in a few small, important ways I am still the boy named Issur Danielovitch who lived near the carpet mills in Amsterdam, New York. If an actor lets himself become blasé, he can’t play the game of let’s pretend, which is the essence of being an actor. He’s lost if he says to himself, “What am I doing here, a grown man, pretending I’m a cowboy? This is ridiculous.”

If you can’t pretend without being self-conscious, if you begin to think, Get me, everybody. I’m an actor, and I’m acting the pants off of this role. You’ll end up by thinking of yourself as a star with a capital S, and you will be a flop with a capital F.

Perhaps I’ve dwelt too long on the odd traits of actors; they have virtues too. The most generous people I’ve ever dealt with are actors and newspapermen. Pass the hat for a needy co-worker in either group and you’d better have a big hat. And no one is willing to work harder than an actor—to the end of his endurance, if need be. This goes for any actor, famous or obscure.

My agent once said of me, “Kirk is always riding me to put out more effort on his behalf. I spend more time on him than I do on any other two stars on my list, so in a way he’s more trouble to me than he’s worth. But it’s only fair to say that the guy drives himself harder than he drives me. ‘Hey, Douglas,’ he tells himself. ‘Do something. Get going! Get off the dime!’”

Whatever drive I have stems from lessons learned a long time ago. When I was working my way through St. Lawrence University, I once lost my small fund of cash in a poker game. Much ashamed, I had to go home to my hard-pressed mother and tell her.

“You are such a fool,” she chided me. “You bet money on cards. What do the cards know about you? What do they care?” She gave me a hug and said, “Everyone likes to gamble. There’s nothing wrong with gambling. You want to bet? O.K., bet. But gamble on yourself.”

I have found that the perfect place to take her advice is in acting. I’ve never hesitated to gamble for really big stakes—abandoning my contract at Warner’s, starting my own independent company, Bryna Productions. I’ve been lucky enough to make a few good pictures, but I don’t assume that I’ll never boot one. No one bats a thousand in any league, and a champ is a guy who walks into the ring one day and gets clobbered by a kid no one ever heard of. All I can do is work as hard as I know how, and, when the chips are down, gamble on myself.

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood. This edition can be ordered here.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Im like you Kirk Douglas.I worked my way through college. I am a 62 year old woman now. I m proud of myself. Im oroud of my 2 grown children who through hard work now make good money. I taught them to enjoy whatever line of work they want to go in. My son is a Fireman/ Paramedic and my daughter is an EMT/Respiratory Therapist. They actually love what they do. Im grateful !