John Kobler, while writing “The Flip-Flop Machines” for the Post in 1968, observed computers that could teach English, play chess, simulate warfare, and write poetry. All of those tasks are readily available on any smart phone now, but his principal reflection on technology remains woefully unexamined: “Machines can’t make a better world without better people, a truism applicable to every material discovery from the wheel to nuclear power.”

In other words, computers are only as good — or as evil — as the intentions of the people behind the keyboard. The recent scandal involving Facebook and Cambridge Analytica shows how vulnerable we are to manipulation. But the phenomenon, while strikingly much more sophisticated than it used to be, isn’t completely new. Ever since computers were developed to process information, it seems, they’ve been used to analyze — and possibly influence — voters.

In the spring of 1960, John F. Kennedy’s campaign was aided by Simulmatics, a computer firm that simulated the election results of various campaign strategies. The “people machine,” developed by social scientists from M.I.T., Columbia, and Yale, used surveys from over 100,000 voters to create 480 “voter types.” The big question posed by the Kennedy campaign, according to Kobler, was whether his Catholicism was a problem. “The net worst has been done,” Simulmatics told them. “Bitter anti-Catholicism would bring about a reaction against prejudice and for Kennedy from Catholics and others who would resent overt prejudice. Under these circumstances, it makes no sense to brush the religious issue under the rug.”

Eugene Burdick expressed prescient concern for Kennedy’s use of Simulmatics in his 1964 novel The 480. The book warns of a powerful new kind of political influencer in the age of computer technology:

“The new underworld is made up of innocent and well-intentioned people who work with slide rules and calculating machines and computers which can retain an almost infinite number of bits of information as well as sort, categorize, and reproduce this information at the press of a button… They may, however, radically reconstruct the American political system, build a new politics, and even modify revered and venerable American institutions.”

The revelation that British firm Cambridge Analytica mined extensive data on more than 80 million Facebook users for Donald Trump’s election campaign was a wake-up call for anyone who still thought social media was a wholly innocuous trend. The company’s powerful algorithms and incredibly substantial field of data allowed it to perform unprecedented research on American voters. The breach violated Facebook’s terms of use, but more than a year after the election that fact seemed immaterial. Many wondered how Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, could have allowed it to happen, but perhaps Stephen Marche put it best in The New Yorker when he wrote, “We blame Mark Zuckerberg because we can’t stand to blame ourselves.”

Zuckerberg has shown public concern for the damage inflicted on his platform. “For most of our existence, we focused on all the good that connecting people can bring,” he said in his official statement to the U.S. Senate, “it’s clear now that we didn’t do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm as well.” It should also be clear now that we will likely hear a version of that statement again and again in the future, if not from Zuckerberg, then from another Silicon Valley CEO who shares his mantra, “Move fast, and break things.”

Although both operations aimed to distill the American voter down to a demographic, there are major differences in depth and scope between the operations of Simulmatics and Cambridge Analytica. According to Chris Wylie, the whistleblower data analyst of Cambridge Analytica, the company created in-depth psychological profiles of millions of people that allowed it to target disinformation tailored to one’s susceptibility. That seems to be more intensely deceptive than an algorithm used to determine whether the public thinks Catholicism is okay, but ethical boundaries can be fuzzy with each new technological innovation taking the public by storm. Wylie compares the difference to a campaign that delivers a message in the public square as opposed to one that whispers in each voter’s ear.

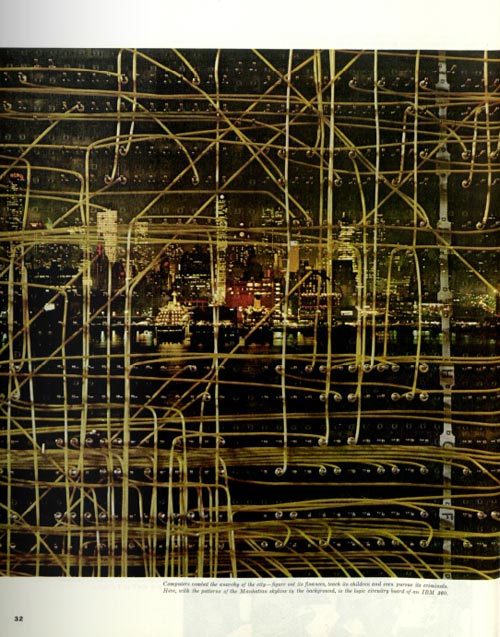

The current reality of touchscreens, and facial recognition, and extensive social networks would have been difficult for Kobler — or Kennedy — to envision. When Kobler wrote “The Flip-Flop Machines,” powerful computers were still resigned to government use. Yet, the scope of how this impending technology would bring about sweeping ethical dilemmas and problematic artificial intelligence was roundly acknowledged. After all, just a month before the feature was published in this magazine, 2001: A Space Odyssey hit American theaters with its foreboding message on the pitfalls of all-encompassing technology: the killer computer’s power was derived from the crew’s complete reliance on it for everyday tasks.

Our pervasive dependence on vast technological systems might seem as though it sprung up out of nowhere, but it’s been a long time coming, and the warning signs were always there. Kobler notes an anecdote among computer scientists about a supercolossal computer built to answer the question, “Is there a God?”

“Yes,” it said at length. “There is a God — now.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This 1968 article is one of the most interesting I’ve ever read. It’s very intense. The technology of computers for that time, again for that time, was at LEAST as advanced as what we have now.

The article is also eerie, especially in the last paragraphs. I think John Kobler would have been impressed with the medical tech advances in the decades since. I don’t think he’d be happy with the tech overkill we have now, and how many (not all) people have become slaves to their smart phones and more and how unhealthy that is.

He’d be unhappy but not surprised at how intrusive, pervasive it is now, calling all the shots, and most people either don’t care, too dumb to care, or it’s been this way for so long now they don’t know the difference.

As an individual, you need to know how to put the brakes on it to the extent you can. Technologies of the past were more “set it and forget it.” While computers and smart phones require more interaction, yes, they need to be kept in check, not unlike food or alcohol consumption. It needs to be in moderation. America largely doesn’t like or do moderation, but it doesn’t make it any less true.

John Kobler passed away on December 11, 2000; just a month after the (then) still undecided victory of either George Bush or Al Gore due to all kinds of primitive malfunctions that if computers weren’t contributing to, they certainly weren’t helping either. I’m pretty certain he was fully aware of that, and very disillusioned.