This article and other features about the golden era of American cars can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, American Cars: 1940s, ’50s & ’60s.

— Originally published March 1962 —

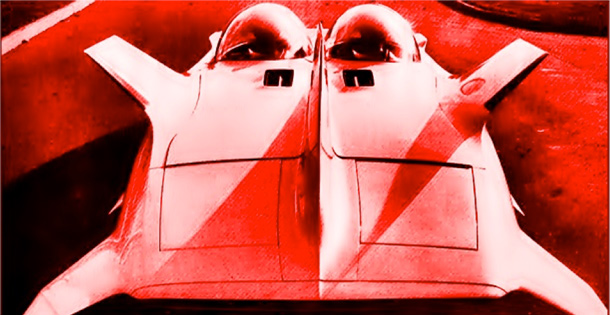

On big airplanes, a turbine engine is known as a turbojet. Turbines are known also on some seagoing vessels, and they are an old story in research laboratories. But a turbine engine is a rare sight in an automobile, certainly in an automobile doing the customary chores of driving — cruising, stopping for the lifted palm of a traffic cop, entering and leaving parking lots, stopping at service-station pumps. To learn how this power plant responds to an average driver, I undertook a coast-to-coast run.

I must confess that I had a copilot. He was George J. Huebner Jr., 51 years old, director of Chrysler Corporation research, and father of the turbine that powered our car. We were attended by seven engineers and mechanics involved in the Chrysler turbine program, who followed us in two conventional station wagons and one camp wagon crammed with rescue and replacement gear. Intercar radiophone linked our fleet, and we clung pretty close to legal speeds, averaging 55.5 mph.

Our car was plainly labeled a turbine test car on a transcontinental test run. Most of the time we wore raincoats with TURBINE RESEARCH lettered on the backs. One of these coats inspired a fundamental question in a little Mexican-American church in Holbrook, Arizona. The wearer, Gerry DeClaire, Huebner’s assistant, heard a small boy in the next pew whisper, “¿Mama, qué es un turbina?”

The question was a good one. The answer is that a gas turbine is a heat engine, something like a bonfire in a closed bucket, and the bucket resembles your pressure cooker at bean-canning time. The fire feeds on any fuel that will pass through the lines to reach the single, continually ignited spark. It is a fierce fire, 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit or more, which creates a whistling gale that is led through two many-bladed turbine wheels, just as the wind passes through a windmill and with the same effect. The gale spins the turbine wheels, up to 46,000 revolutions per minute.

The first of these miniature windmills spins a compressor which squeezes, and consequently heats, incoming air to be mixed with fuel in the fire chamber. The second turbine, its speed stepped down by reducing gears, drives the prop shaft that drives the rear wheels.

Did the car feel right and sound right? Would it be awkward to maneuver along the frantic rat race of Lindbergh Boulevard in St. Louis or along the Pasadena Freeway into Los Angeles? Would it soar or struggle up the grade to 7,250 feet at Campbell’s Pass in New Mexico? Would it start easily on zero-degree mornings? How much fuel would it use?

Let me say at once that I would be delighted to step into the turbine car tomorrow morning and travel any of these stretches or meet any of these conditions. And I did.

Huebner believes that plenty of others would like and would buy turbine cars if the cost was comparable. So, for the first time an automobile manufacturing company is apparently willing to consider a market test of a gas-turbine car. They need reactions from users, and I was the first long-distance trial horse. Publicly, Chrysler has said it will market 50 to 75 turbine cars. Privately, however, some company voices are suggesting more — hundreds, thousands, perhaps tens of thousands.

Looking Further Ahead

The major significance of the turbine car is that it represents Detroit’s first radical departure from the piston engine. But the gas-turbine engine is only one of a number of developments in the industry.

Recently I rode in an automobile that accelerated, slowed, stopped, and steered — with the driver’s seat empty. I have operated a rudimentary wheel-less vehicle. I have handled a car which was steered, accelerated, and braked by a short stick. I have seen and discussed with research scientists more than a half-dozen advanced-design automobile engines

A popular rear-engine car has been solidly established. So has a car with a rear-end transmission. Artist Salvador Dalí has invented a passenger-carrying plastic bubble that rolls like a ball, and several cities have imported taxicabs propelled by light diesel engines. But neither of these developments is causing a major impact on our auto industry. Where, then, are the revolutionary “dream cars” that were so freely prophesied just after World War II?

We have seen important changes, of course. The driverless car, for example, is eight years old. A joint development of the Radio Corporation of America and General Motors, it is in operation on a quarter-mile experimental track near Princeton, New Jersey. It works, and it could (at great expense) be installed tomorrow on any automobile and any highway.

I had an eerie sensation while riding on the Princeton track alongside an empty driver’s seat — and a similar feeling of unreality while operating a small experimental airborne machine at the Ford Motor Company’s research and engineering laboratories in Dearborn. It is a so-called ground-effect machine which substitutes a cushion of air for wheels. Riding on it is like gliding across a sheet of glare ice which has been specially polished and then greased.

Ford’s engineers predict a wheel-less automobile within the next century; and they are almost certain that fuel injection, replacing our present carburetion, will become common in passenger cars in the next few years.

European research engineers recently road-tested a rotary engine — a sort of spinning triangle without pistons. American Motors is trying to extend the present short-range capabilities of battery-operated electric cars.

Present research efforts certainly will pay off in the future — and no one will deny that an unexpected breakthrough could occur at any time. But so far the engineering, production, and economic problems are a powerful restraint. A new car or a new engine must show enough superiority to justify the staggering cost of replacing our present manufacturing and service facilities.

Then there is Unicontrol, which GM engineers are excited about. It’s a short gear stick that controls the acceleration and deceleration, steering and braking of the ordinary car bodies that house it. The little stick sends commands to the steering, throttle, and brake mechanisms — and if it is placed between the driver and front-seat passenger, either may operate it.

The term “fuel cell” is a loose expression for the production of electric current by chemical reaction. A common storage battery is a fuel cell of sorts. So is the human body, which is able to consume cake and cauliflower and produce brain currents of measurable voltage. This chemical production of electric energy has an aspect that fascinates all the automotive scientists. A chemical engine would be twice as efficient as a heat engine, such as our present internal-combustion engine. The fuel cell requires only about a quarter as much fuel as your car now uses because it wastes so little energy. Unhappily the weight of today’s fuel cell and accompanying motor is about 30 times that of our gas engine. Many laboratories outside of the automotive industry are attempting to develop lightweight fuel cells.

Westinghouse Corporation, one of the firms investigating fuel-cell potentialities, also is investigating a transportation plan which smacks of Buck Rogers. Westinghouse has proposed a sort of private railroad system — without rails — for automobiles. The roadbed would consist of a series of spaced rollers, spun at high speed by electric motors. Gliding or skidding along the rollers would be supercars capable of carrying a number of automobiles and their passengers. Motorists would drive aboard one of the supercars, then be carried at very high speeds to the stop nearest their destination. At such points they would be pushed off the “roller road” to continue in local traffic.

Such nebulous schemes hold a degree of fascination but no certainty of development. Automobiles will certainly be improved by 1975. They will be more economical to operate, if only because we are now ready to accept improved aerodynamics and functional streamlining. Driving will undoubtedly be made easier by new driver aids as important as the power steering and power brakes introduced in the years just passed.

Foolproof and service-free cars may be expected — and they will be lighter in weight, owing to increased use of aluminum and plastic. The true dream cars of the next dozen years should be smaller and no more powerful than current models. The showroom displays may include gas-turbine cars, which could come on with a rush. They may even include a suddenly developed small fuel-cell power plant. But don’t be surprised if they also include a very large share of vehicles with four wheels, gas-piston engines, and a convenient spot where a cop can place the parking ticket.

—“Cars of Tomorrow,” March 24–31, 1962

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now