1963 was a pivotal moment in the history of the civil rights movement. It was the year that Martin Luther King wrote his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” attesting that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” It was also the year of the March on Washington, where Dr. King delivered his unforgettable “I Have a Dream” speech. 1963 also saw a series of widespread marches in Birmingham, Alabama, including a “Children’s Crusade” composed of thousands of protestors of high school age and younger [see sidebar]. Just a month later, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated in the driveway of his home in Jackson, Mississippi.

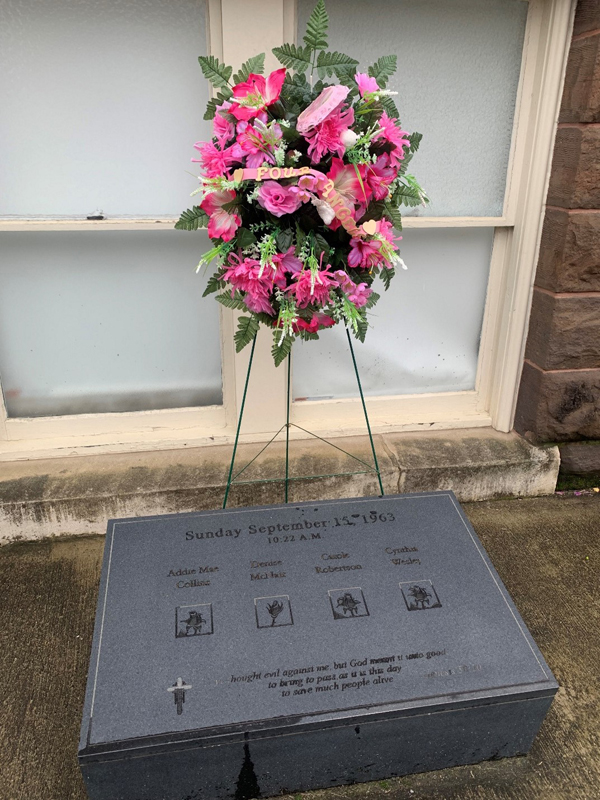

But perhaps most unforgettable of all, September 15, 1963, was the day when four little girls lost their lives in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, a violent act that so deeply shocked the nation, its horror was only surpassed by the assassination of John F. Kennedy two months later.

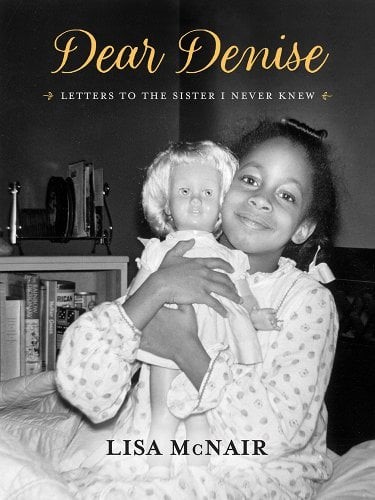

The families of those four girls — Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, all age 14, and Denise McNair, age 11 — were unwillingly thrust into the limelight, their personal tragedies on display to the entire world. On the 60th anniversary of the bombing, the story of one of those families has been recounted in the form of a book entitled Dear Denise: Letters to the Sister I Never Knew, written by Lisa McNair, who was born nearly a year to the date after her sister Denise’s murder.

An extraordinarily moving account of her own journey, as well as that of her parents and her sister, Kim, born four years after Lisa, the book takes the form of a series of letters Lisa has composed to her late sister over the course of many years. In it, Lisa tells Denise about the key moments in her life, but also poses questions to her sister, wondering what Denise’s take would have been on events that happened in the South after her death. As Lisa puts it in the introduction to her book, “I stand on the shoulders of my sister Denise, and as proud as I am to do so, I often wish I could have just cried on those shoulders while talking to her about school, about life, and about my dreams.”

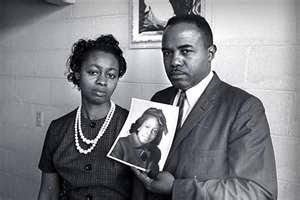

Lisa recounts how Denise’s absence in their family nevertheless gave her a continuing presence in the form of her parents’ grief. She recalls watching the film footage of Denise’s funeral, and even though she couldn’t actually see her mother, she was able to distinguish her distinctive sobs among the crowd. There were trips to the cemetery on the anniversary of the murders, as well as remembrances on Denise’s birthday, and to this day photos of Denise are prominently displayed in the family home where Lisa and her sister still reside after the deaths of their mother and father. “But most of the time, my parents just had to keep it real for us — making sure we got to school, got our homework done, and brushed our teeth. So, most days were pretty routine. But Denise was never far from any of our minds,” Lisa explains.

Just having the name of McNair meant being in a fishbowl in the Birmingham community. “You could never fully get away from what happened,” Lisa says. “I was always a little uncomfortable and wanted just to fade into the background, but that was never in the cards for us.” For Lisa’s father, Christopher, his grief propelled him into a life of civic activism. In 1973, he was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives, the first Black representative from Jefferson County, where Birmingham is located. Serving until 1981, McNair was immensely popular among both his Black and white constituents in a district that was among the last to remove the “Whites Only” signage following desegregation. From 1986 to 2001, he then served as a county commissioner in Birmingham. Her mother, Maxine, taught third grade for many years, and Lisa still finds herself from time to time being told by former students of the impact her mother had on their education and on their lives.

Addressing Denise in her book, Lisa writes, “What Mamma and Daddy did after your death was quite special. They could have been mean, bitter, and hateful, but they were determined to make something positive out of their tragedy.” Elsewhere, Lisa tells Denise, “The way Daddy and Mamma handled themselves after the bombing also earned them the respect of even some of the most hateful racists. Our parents…modeled forgiveness and bucked the status quo to create a life for us in this city. I am proud of them for that, and I’m sure you would be too.”

Lisa is unflinchingly honest throughout the book, even with topics that aren’t particularly flattering to herself. A major theme is her struggle to accept her own Black identity. The church bombing paved the way for the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act, which both in Birmingham and across the nation meant the beginnings of desegregation. Lisa’s parents were able to enroll her in a private elementary school, where she was only one of two Black children in her class. She received a superior education, even studying French, but found herself becoming more and more acclimatized to the white culture of her classmates.

When she socialized with Black peers, she felt out of touch with such cultural matters as their music, clothing, and the slang they used. She found herself criticized and ostracized, with some people going so far as to call her “a white girl” and telling her she “wasn’t Black enough.” After years of struggle, Lisa now feels she has integrated the two elements of her personality. She says “there is a white girl inside of me…But make no mistake: I will forever be Black. No one can ever take that history or experience from me. All Black folks aren’t alike. No one can paint us all with a wide brush. I am very comfortable in my skin now and love both sides of me.”

Other honest assessments that Lisa undertakes include a recounting of her father’s conviction and subsequent imprisonment due to charges of bribery and corruption after a group of his friends decided to help him add an art gallery to his photography business. These friends had business with the county in which her father was serving as commissioner, giving the appearance of a quid pro quo, when Lisa insists there was none.

Lisa also tells Denise about the trials and convictions of several of the bombers, which took place many years after the murders; witnesses were reluctant to talk, and physical evidence was lacking. The first, Robert Chambliss, known locally as “Dynamite Bob,” had the nerve to write to the McNairs after his 1977 conviction and ask them for their help in getting him out of jail. Years later, Lisa found herself standing in a courthouse hallway next to another of the bombers, Bobby Cherry. Lisa felt the urge to ask Cherry, “Why do you hate Black people so much?” but chose to remain silent out of concern the interaction would jeopardize the trial’s outcome.

Lisa also tells of her meeting with the daughter of another of the bombers, who had chosen to shun her family’s racist history. After a long period of trepidation about meeting the woman, Lisa finally did so and had a very public reconciliation with her during a church service. As Lisa tells Denise: “I told her I appreciated her taking her shame and pain out from under the rug and dealing with it. We hugged. She was crying, and so was I.”

The book also includes her recollection of Spike Lee’s visits to Birmingham in preparation for his 1997 documentary, “4 Little Girls,” which features interviews with family members of the four girls who were killed. Both Lisa’s mother and father were interviewed separately, with her father recounting a story of how painful it was for him to tell Denise they couldn’t eat at a downtown lunch counter because they were Black. Lisa also tells how agonizing it was for her mother to discuss the morning of the bombing. Mrs. McNair was in another part of the church when the bomb exploded just outside the church basement, where the girls had gathered in the ladies’ room preparing for what was going to be a Youth Sunday service. Crying out, “My baby! My baby!” Mrs. McNair seemed to know immediately what had happened. Lisa said she learned more about her late sister’s personality during these interviews with Spike Lee than in all the decades that had preceded it. “I learned she was precocious, smart, and lively and definitely spoke her own mind,” Lisa says.

In 1983, the McNairs and most of the rest of the congregation of the 16th Street Baptist Church made the difficult decision to leave the church and to worship elsewhere after a small but very strident portion of the congregation went to extreme measures to oust the pastor, who had introduced modest reforms they objected to; that noisy minority went so far as to carry guns into the church and to take the minister to court. Today, Lisa, who remains devoutly focused on her faith, worships at a largely white congregation, Dawson Memorial Baptist Church, which is welcoming to both Black and Hispanic congregants. “In a sense, your death, along with the deaths of other Civil Rights heroes, made it possible for me to be free to go worship wherever I want, wherever God wants me to go,” Lisa writes.

Sixty years after her sister’s murder, Lisa travels the country lecturing and promoting harmony among the races. Frequent themes she touches on are “How Big Is Your Circle?” encouraging people of different backgrounds to mingle and share points of view, and “Change the Recordings in Your Head,” urging people to challenge any stereotypical notions they might have toward entire groups of people. She also touches on the story of her family, about how the events of 1963 led to the passage the following year of the historic 1964 Civil Rights Act, outlawing the segregation Denise McNair faced in her short life.

But although many changes have come in the past six decades, Lisa McNair acknowledges that much work remains. “There are a lot of changes that still need to be made in the hearts and minds of many people, but I still am convinced we can all learn to live in harmony and peace,” she says. “That’s my dream every day. It’s what I live for.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Absolutely sad story. Hatred and prejudice are the worst evil invented by humans. I greatly admire the way the family stayed positive and played a constructive role in their community. God will greet these angels in Heaven!

Lisa McNair is an extraordinary woman having lived her entire life in the aftermath of his horrific event. She’s managed to keep the legacy of this personal and national tragedy alive to learn from in the broadest sense. She has lessons for every American. To those who unfortunately are still racist, may they be inspired to take a long look at themselves in the mirror to ask why, and then have the resolve to finally move forward. It’s never too late to start.