25 years ago, a small group of people completed two years of living in the Biosphere, a self-sustaining dome in the Arizona desert. The idea of an independent, self-supporting community of people dedicated to communal living has predecessors dating back to the early 1800s, but it’s rarely led to success.

The United States was meant to be a utopia. It was created with the most advanced thinking of its time, and it promised its citizens the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. What other 18th century government was making an offer like that?

But some idealists thought this was just a beginning. They dreamed of building communities where people could achieve even greater enlightenment, morality, and harmony.

In the 1840s, the country experienced a massive utopian movement: in just ten years, 80 utopian communities sprang up. Ralph Waldo Emerson said just about any many who could read carried the draft of a new community in his vest pocket.

The Harmonists

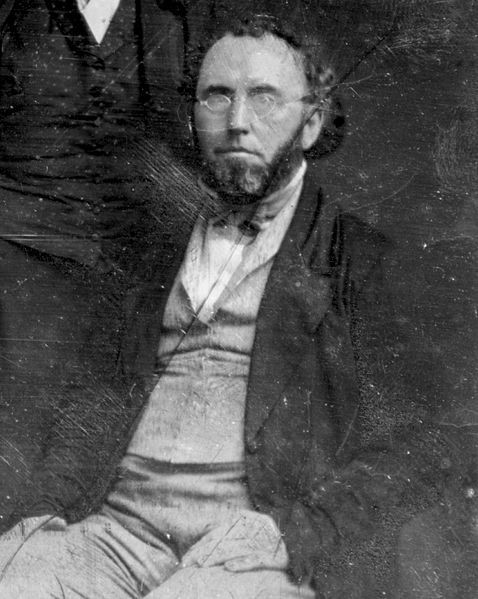

One of the earliest of America’s utopian dreamers was Johann Rapp, who came to America from Germany to escape religious persecution.

Believing the world would soon end, Rapp wanted to return to the principles of the early Christians. Along with his followers, called Harmonists or Rappites, he built two communities in the Midwest before settling in Economy, Pennsylvania.

His followers recognized no worldly authority, and so refused to be drafted or to take oaths. Members all wore the same style of clothes and lived in the same style of house. They also practiced celibacy, which meant the community only survived by recruiting new members.

What saved the Harmonists was realizing their community would be more prosperous if it pursued manufacturing instead of farming. They even started an oil company after the Civil War. It was this practicality that enabled the Harmonist community to last for 100 years.

Brook Farm and Fruitlands

In 1841, a Unitarian minister named George Ripley started Brook Farm, a commune that would enable members to pursue their own literary and scientific endeavors.

It was intended to be an agricultural commune, but its members, many of them transcendentalist philosophers like Ripley, didn’t know the first thing about farming.

Money troubles and arguments among members caused Brook Farm to fold in five years.

Undeterred by news of Brook Farm, another commune was started 35 miles away by Bronson Alcott, father of Louisa May Alcott.

Looking back, its’ surprising that Fruitlands lasted as long as it did, considering the stringent rules members had to follow. They were forbidden meat, alcohol, coffee, milk, tea, artificial light, hot baths, or the use of animals for riding, food, or farm work.

Charles Lane, the cofounder, also wanted to impose celibacy on members, but Alcott had already brought his wife and children to his house in the commune.

One of Fruitlands’ goals was to escape the materialism of capitalist society. Another was to avoid harming anyone or anything, including pests that destroyed the fruit and crops.

The first winter was enough to convince the members to ditch the farm and head back to their comfortable lives.

The Owenites

Robert Owen was another utopian dreamer. In 1825, he purchased New Harmony, Indiana (from George Rapp, actually, when Rapp decided to move his Harmonists to Pennsylvania) and convinced some of the country’s most brilliant scientists to join him. Together, they would create a community that would let them all pursue their scientific studies.

Owen believed his community would be the incubator of revolutionary ideas that would improve society. But in the end, all that scientific expertise proved of minimal help in carving a modern community out of the wilderness. Many members were unfit or unwilling to do the necessary hard work. When the members began squabbling about money, the commune was divided among Owen’s five children, who managed to carry on some scientific research on a smaller scale.

One former member, Josiah Warren, said of his experience at New Harmony, “it was nature’s own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us….Our ‘united interests’ were directly at war with the instinct of self-preservation.”

The Shakers

Many utopian groups were founded on religious principles. The Shakers were one of the more memorable and widespread. They called themselves the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, but got their nickname from their style of worship, which could involve shaking, whirling, or dancing.

The Shakers came to America from Britain in 1774 and set up several communes in Pennsylvania and the Midwest. Members shared all work and all rewards. They began making furniture, which gained a lasting reputation for its austere, simple beauty.

The Shakers were one of the first groups to recognize gender equality, though men and women lived and worked separately. They also practiced celibacy, which meant be no new Shakers would be born into the community. They had to rely on converts who were willing to accept a life of simplicity and hard work to keep Shaker ideals alive. The Shakers also adopted orphans.

By the mid-1800s, there were 6,000 Shakers in America. Today, there are just two, living in Maine, and they have decided to accept no more converts into their faith.

Communes of the 1960s

Communal living became popular again in the 1960s, as young people rebelled against mainstream American society.

They believed communes would let them escape materialism, sexism, racism, militarism, and, occasionally, clothing. Some communes quickly failed, but some lasted for years because they attracted people with a sense of common purpose and belief in independence and sustainability.

These communes pioneered the healthy food movement, as well as the self-reliance that has been adopted by survivalists. It was hippie communes that helped introduce America to organic foods, vegetable proteins, brown rice, and the move away from preservatives and artificial coloring.

Some faded away as members explored new opportunities. But they’re not all gone.

Twin Oaks, Virginia, has been in operation since 1967. Its members are dedicated to cooperation, equality, non-violence, sustainability, and income sharing.

Disappearing Utopias

So why do utopian communities disappear?

Forbes writer Mark Hodak believes that communes often fail when a charismatic founder dies and can’t be replaced.

Also, many commune members are more focused on resisting the challenges from outside and overlook the factions within the community that eventually split it apart. An additional problem is that most communes don’t have a workable plan to sustain themselves. They rely on members working out of a sense of loyalty, but the longest-lived communes ran as businesses. Lastly, there’s that contrary side of people that just wants to rebel against rules. That might be the reason what might be considered the first Utopia — Adam and Eve — failed.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

An interesting report on creating further utopias within what was already supposed to be one: the United States itself, over the past 200 years.

Like the mirage of water in the desert heat, there’s always that underlying desire for perfection just under the surface. I’m impressed with the 19th century attempts to create such utopias by Johann Rapp, George Ripley, Bronson Alcott, Robert Owen and the Shakers.

It looks like Twin Oaks from the ’60s has been the most successful, and has a bright future. Thanks for the link; I’m impressed. Being well organized (run like a business) but retaining the humanity, seems to be the key.

I love the ‘Wizard of Oz’ inspired illustration at the top. We’re all looking for that elusive yellow brick road to take us to that Emerald City. Part of the subliminal appeal of the film is the illusion of finding perfection. Leaving the sepia-toned Depression and walking into that Technicolor.

My (late) mother’s scarring Depression childhood has been well known to me most of my life. Too many times she got her hopes up only to have them dashed. The one place (in this life) she found that utopia was when we went to Disneyland in the ’60s and ’70s. Uncrowded, inexpensive, clean and beautiful, it was all she imagined it to be, and more. I always had a great time there too, but not like she did, and I know why.

Today Disneyland is NOT the same. Overcrowded, extremely expensive, it’s bigger than ever now, yet is a shadow of its former self she would hardly recognize. No, I like to think Mom’s in an everlasting Xanadu of perfection with shooting stars, neon lights and so much more.