When the Enterprise began its maiden voyage in 1966, few suspected that they were witnessing the launch of one of the most important and enduring franchises in the history of television. More than 50 years later, Star Trek consists of six television series (with one in development), 13 films, an animated series (with another pending), and countless tie-in novels, comic books, and games. The original series repeatedly broke new ground, but perhaps no moment was more shocking to the sensibilities of 1960s viewers than a scene in the November 22, 1968, episode, Plato’s Stepchildren; in that moment, Star Trek broke a cultural taboo by broadcasting TV’s first interracial kiss.

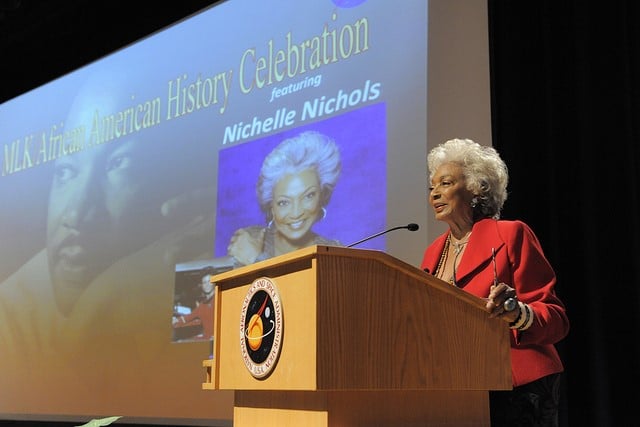

It’s fair to say that Star Trek pushed boundaries from the beginning. After a false start with an initial pilot that featured a largely different cast (which was later integrated into the episode “The Cage”) including a female first officer, Star Trek debuted in 1966 with the episode “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” The first season introduced most of the familiar, iconic cast: Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner); Mr. Spock (Leonard Nimoy); Dr. Leonard McCoy (DeForest Kelley); Lt. Hiarku Sulu (George Takei); Lt. Commander Montgomery Scott (James Doohan); and Lt. Nyota Uhura (Nichelle Nichols). As communications officer aboard a Starfleet vessel, Lt. Uhura is considered one of the first African-American women on television to hold a job of particular distinction.

Series creator Gene Roddenberry and a murderer’s row of some of the most talented writers in speculative fiction told stories that went beyond the conventional action series of the day. They explored social issues and concepts that other shows avoided; Star Trek’s science fiction milieu allowed them to use more metaphorical approaches for tackling racial inequality, fascism, and other hot-button topics. Though dogged by lower ratings in the second season, the show was renewed based on two factors.

One was that the demographic that the show attracted was considered “high-quality” and desirable because the fanbase consisted of many professionals in science, law and medicine. The other major factor was an aggressive writing campaign from fans urging NBC to give the show a third season; while Trek already received the second largest amount of fan mail in television (behind only The Monkees), the write-in campaign eclipsed any previous outpouring for a show. A whopping 52,000 letters hit NBC in February of 1968 alone. They got their renewal.

Headed into the third season, the show’s overall prospects were bleak. Budgets had been cut, and the show’s timeline had been moved to Fridays at 10 p.m., which is traditionally bad news for a show that leaned in part on a young viewership. A dissatisfied Roddenberry had less hands-on involvement with each episode, but the writers kept pursuing social concerns. That came to a head with the 10th episode of the season, Plato’s Stepchildren. In the episode, the crew runs afoul of telekinetic aliens who base their civilization on Earth’s ancient Greece; the aliens use their powers to force the crew into various situations, including making Kirk and Uhura, against their will, kiss.

Though the certainty of this moment as the first interracial kiss on television has been debated, it certainly appears to be the first scripted kiss between a white man and a black woman in an America series. It also occurred only a few months after the Supreme Court handed down their decision in Loving v. Virginia, the case that struck down state laws banning interracial marriage in the United States. In her book Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories, Nichols recalled that NBC was afraid that the kiss would anger viewers in the South. Two versions of the scene were filmed, one with and one without the kiss. However, Nichols recalled that she and Shatner intentionally blew the non-kiss takes so that the kiss would have to be used. In her book, she went on to say that nearly all of the fan mail they received after the episode was positive, with only one slightly negative letter that stated, “I am totally opposed to the mixing of the races. However, any time a red-blooded American boy like Captain Kirk gets a beautiful dame in his arms that looks like Uhura, he ain’t gonna fight it.”

While the kiss is considered an important moment for the erosion of barriers on television, the impact of Uhura and Nichols on the progress of women and African-Americans can’t be underestimated. Early during the series run, Nichols had considered leaving the show for Broadway, but a chance meeting with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at an NAACP fundraiser changed her mind. King told her that he was a huge fan and insisted that she stick with the show because she was making history by showing African-Americans as a valued part of the future. Nichols literally shaped the future of America in space when she later worked with NASA as a recruiter of women and minority astronaut candidates; her recruits included Dr. Sally Ride, the first American woman in space, and USAF Colonel Guion Bluford, the first African-American in space. Asteroid 68410 Nichols was named after her in 2001.

Today, it’s not unusual to see interracial couples and diverse casts on American television. Highly rated shows like Grey’s Anatomy and NBC’s multi-series Chicago franchise showcase a variety of relationships, and series like Black-ish and Fresh Off the Boat deliver the perspectives of families and cultures outside the realm of whiteness. Gene Roddenberry wanted Star Trek to show an inclusive, cooperative future; in several small ways, it helped make that future possible.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The writer means it can’t be overestimated, not underestimated. This is a common error, an English construction which has bollixed me occasionally, too.

Nichelle Nichols has always been a class act, and still is. I clicked her interview on the Archives of American Television interview as well after reading this feature. She’s definitely a star I’d like to meet. I recently got to meet and talk to both Tatum O’Neal and Mackenzie Phillips at the Westin near LAX. Two great women—and survivors!

As for Shatner himself, I met him by accident doing some photocopying at around 11:30 at night in 2006 at the Kinko’s (long since Fed Ex Office). We were the only ones there. I hesitated to approach him, but only at first. He was very nice, and really lit up when I said how much I admired his work on ‘Boston Legal’ right away, referencing various episodes. Naturally I knew enough to never mentioned ‘Star Trek’ Troy, and did not!

Very interesting article on the first interracial kiss. To put my own insights into it, the fact that it was ‘reluctant’ and there were forces at work ‘forcing them’ to, I’m sure helped to cool any waters of controversy. Indeed, there was only one letter barely opposing it. Let’s not forget either, that it was Lucille Ball that got ‘Star Trek’ the green light when it had been rejected by everyone else.