The mid-term elections took place nearly two weeks ago, and states are still dealing with claims of voter suppression and fraud, wrangling over which votes are valid and which aren’t, and watching over razor thin victories that hinge on just a few ballots. These days, every vote really does count … or does it?

Despite the fact that there is little evidence of modern voter fraud, issues such as disinformation, gerrymandering, and disenfranchisement still plague our electoral process. Here is a brief history of how party bosses and partisan bullies have tried to swing elections in their favor.

Intimidation

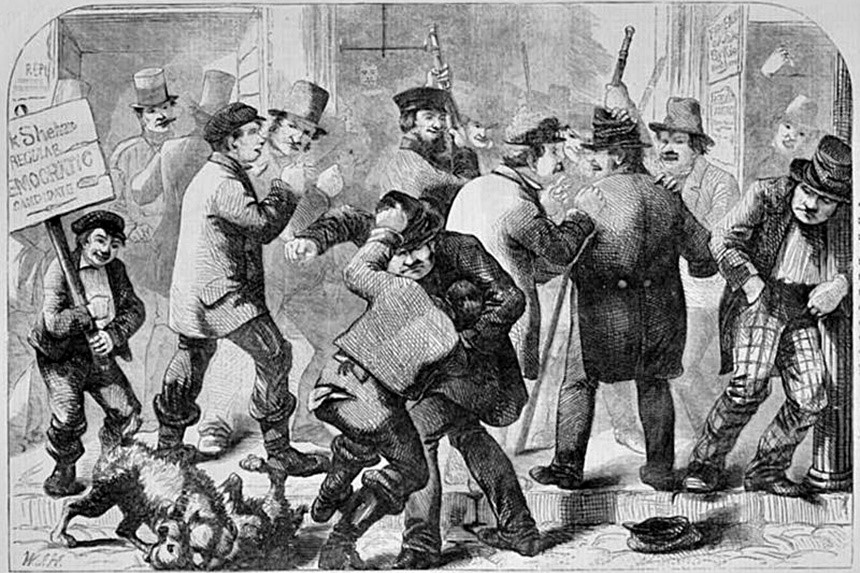

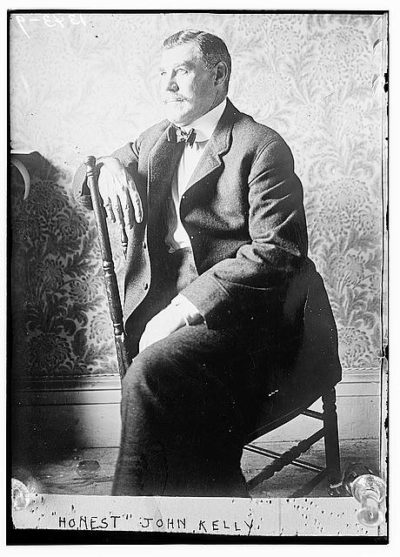

In the 19th century, unscrupulous politicians stole elections by force. Political bosses in 1850s New York led teams of thugs to the polling places to threaten anyone voting “the wrong way.” And people like “Honest John” Kelly, with his army of rowdies, broke into a polling station, smashed the furniture, and tore up all ballots cast for his opponent.

By 1892, every state in the union was using private ballots, making it more challenging for crooked campaign workers to intimidate, blackmail, or bribe voters. But that doesn’t mean that intimidation stopped.

A story from the May 8, 1908, Saturday Evening Post describes one of the more imaginative intimidation tactics. A southern precinct consisted of 487 black voters and 36 white ones. Soon before election day, news spread that a former Union general from Washington — a close friend of General Grant’s — was planning to visit to encourage black voters to cast their ballot without fear of reprisal.

On election day, the “general” arrived in full dress uniform, with ranks of medals glittering on his chest. The black voters cheered this warrior of the Union cause.

Suddenly, a group of masked horsemen rushed out of the nearby woods, threw a noose around his neck, and carried him away. The audience stared after them in shock. If racists in their community could lynch a friend of the president’s, they thought, what protection would they have? The crowd melted away from the polling station. At the end of the day, the 36 white citizens had voted, but none of the 487 black citizens had.

Meanwhile, the general and the horsemen pulled up in a lonely crossroad. The general freed his hands, took the noose from his neck, and handed it back to one of the “lynching party.” He then rode away to repeat the performance in another village. According to his own account, he was “shot” or “stabbed” at gatherings in several locations.

Ballot Tampering

One of the easier ways to make an election go in your favor was simply to get rid of ballots from polling stations in areas supporting your opponent, or suddenly discover extra ballots that favored your side. This is what occurred in 1948, in the Ballot Box 13 scandal, when a box containing 202 additional ballots was found in a Texas precinct — just enough to swing the election and elect Lyndon Johnson to the Senate.

Or you could switch ballots. A Post article from the early 20th century relates the story of a regional election where the balloting was supervised by two Republican and two Democratic judges. At the end of the day, the two Republican judges were invited to dinner but declined, saying they had to watch the ballot box until it was delivered to the county seat. Someone suggested the judges lock the box in a nearby wardrobe closet. The judges agreed and ate dinner while keeping an eye on the locked wardrobe. They didn’t know that a man had been hidden inside to remove Republican votes and replace them with Democratic ballots.

An even simpler method was used by New York’s Democratic political machine in the 1870s. The party made certain that loyalists in each ward reported a favorable total, regardless of what the ballots said.

Disenfranchisement

In the early days of America, voting was restricted to white male landowners. The idea of throwing open the doors of democracy to everyone was horrifying to many. In 1776, John Adams wrote:

Depend upon it, Sir, it is dangerous to open so fruitful a source of controversy and altercation as would be opened by attempting to alter the qualifications of voters; there will be no end to it. New claims will arise; women will demand the vote; lads from 12 to 21 will think their rights not enough attended to; and every man who has not a farthing, will demand an equal voice with any other, in all acts of state. It tends to confound and destroy all distinctions, and prostrate all ranks to one common level.

Over time, women, African Americans, and other disenfranchised groups fought for and received the right to vote, but that didn’t stop obstacles from being thrown in their paths.

In the years following the Civil War, white politicians in Southern states held onto power by devising tests that would disqualify black voters. One sure way to block ex-slaves from voting was to require them to prove they could read and write. (It had been illegal to teach literacy to slaves.) As black voters learned to read, the tests became more difficult.

Literacy tests were banned in 1965 as part of the Voting Rights Act.

Another method of disenfranchising voters was the poll tax. Many poor African Americans couldn’t afford the $1-2 tax. These limitations would have applied to uneducated, poor white voters as well, but the legislatures enacted “grandfather laws,” which allowed anyone to vote whose ancestor had voted prior to 1871. That neatly excluded all blacks.

Gerrymandering

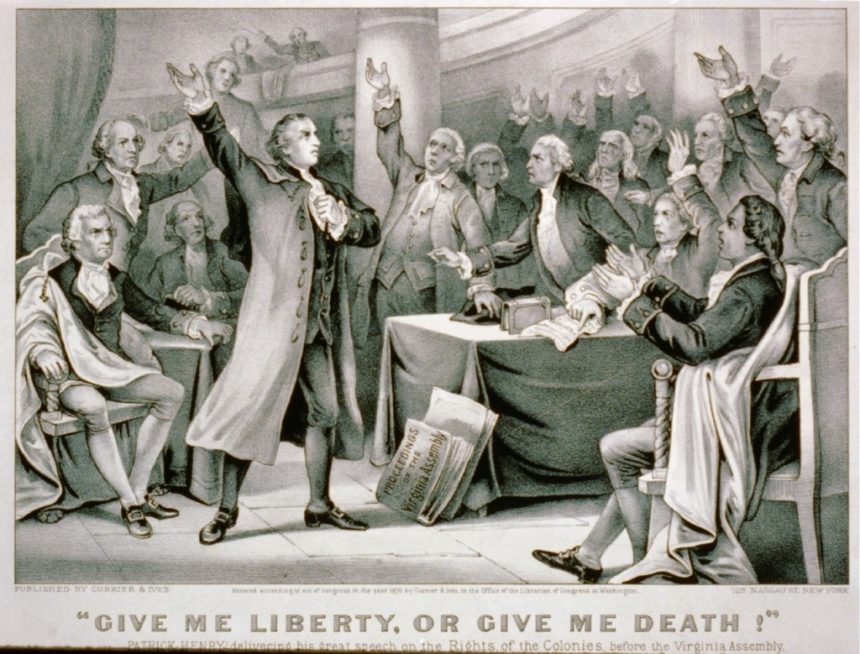

Cracking, packing, hijacking, and kidnapping are all colorful terms for different types of gerrymandering, the practice of drawing the boundaries of a political district to favor one party over another. It was being done in the U.S. as far back as 1788, when Patrick Henry of “Give me liberty of give me death” fame persuaded the Virginia state legislature to redraw the boundaries of the 5th congressional district so his political foe, James Madison, would lose against James Monroe in the election of U.S. Representative. Madison ended up winning anyway.

Disinformation

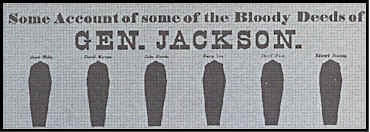

Deliberately spreading false information about a candidate or party is an age-old tradition. In the 1828 presidential election, a series of handbills were distributed defaming Andrew Jackson, and included accusations of adultery, bigamy, and cannibalism. One bill claimed Jackson’s mother was a prostitute.

Caging

Caging is a tactic in which campaign workers for Party A send registered letters to voters who are registered to vote for Party B. If the letters are returned because of address inconsistencies, clerical errors, or a changed address, the campaign workers could challenge those voters’ registration.

The most notorious example of caging occurred in 1964, when a Republican campaign known as Operation Eagle Eye sent 1.8 million mailings to voters in 15 cities with large minority populations, including Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Kansas City, and St. Louis. The undeliverable mail was returned to a local address, and local campaign workers were instructed to challenge the qualifications of anyone with a returned letter. Program officials stated that at least 2,963 names in Chicago alone were purged from the rolls before the election, based on the caging lists generated by this campaign. Caging was declared illegal under the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Vote Buying

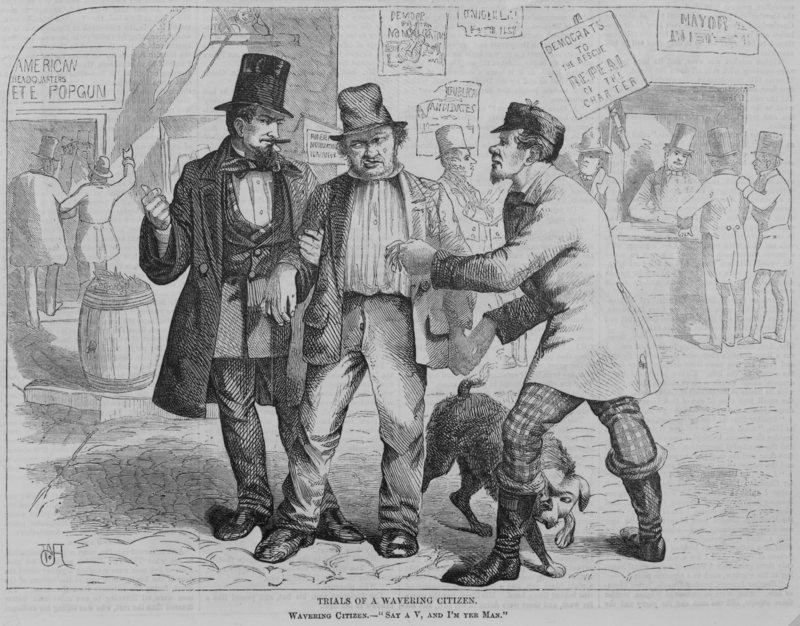

Politicians buying votes in 1857 as depicted in Harper’s Weekly. (Library of Congress)

Vote buying became more difficult after ballots became secret, but shenanigans still occurred. A voter would be given a filled-in ballot before entering the polling station. He would cast his vote with the completed fake ballot and then give the real blank ballot he received in the polling station to another voter waiting outside. The next voter would then fill out the official ballot to the buyer’s satisfaction, repeating the process. This method of vote buying was called the Tasmanian dodge. A much easier cheat was simply to pay people not to vote at all.

H.L. Mencken once said, “Every election is sort of an advance auction sale of stolen goods.” But as Americans, we hope it to be more than that. Certain factions will always look for ways to tip election results in their favor, and it’s up to the rest of us to try to keep their thumbs off the scale.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now