Henry Ford’s influence on 20th-century manufacturing is a well-trodden story. Few would discuss American industry without mentioning the automobile titan’s assembly lines and business philosophy. Absent from many accounts of the rise of Motor City, however, is Albert Kahn, a workaholic architect who made Ford’s dreams possible.

Today marks the 150th anniversary of Albert Kahn’s birth. Like Ford’s company, Kahn’s architectural firm is still in business. While he was at the helm, the visionary designed more than 2,000 factories, towers, commercial buildings, and military facilities. He has been regarded as the country’s most influential industrial architect for creating the perfect spaces for American industry to thrive when the stakes were higher than ever.

Kahn’s family immigrated to the U.S. from Germany in 1881. He was fired from his first job as an office boy at an architectural firm, but soon found another at Mason and Rice, where Detroit architect George D. Mason took notice of Kahn’s dedication. After earning a scholarship and touring Europe with Henry Bacon (who designed the Lincoln Memorial), Kahn returned to Mason’s firm with a deeper appreciation of architecture — and a promotion to chief designer.

By 1895, Kahn had left Mason and Rice to form his own company, which would become Albert Kahn Associates. With the help of his brother, who studied engineering at the University of Michigan, Kahn’s firm operated under the philosophy that architecture was “90 percent business and 10 percent art.” They introduced booming Detroit to factories made of steel and reinforced concrete. Previously, factories had been built from wood, which was much more prone to catching fire and often vibrated when heavy machinery was run. Kahn’s concrete factories, the first being Packard Building No. 10, were revolutionary. They allowed for more uninterrupted space inside and incorporated larger windows to provide natural light and air flow for workers.

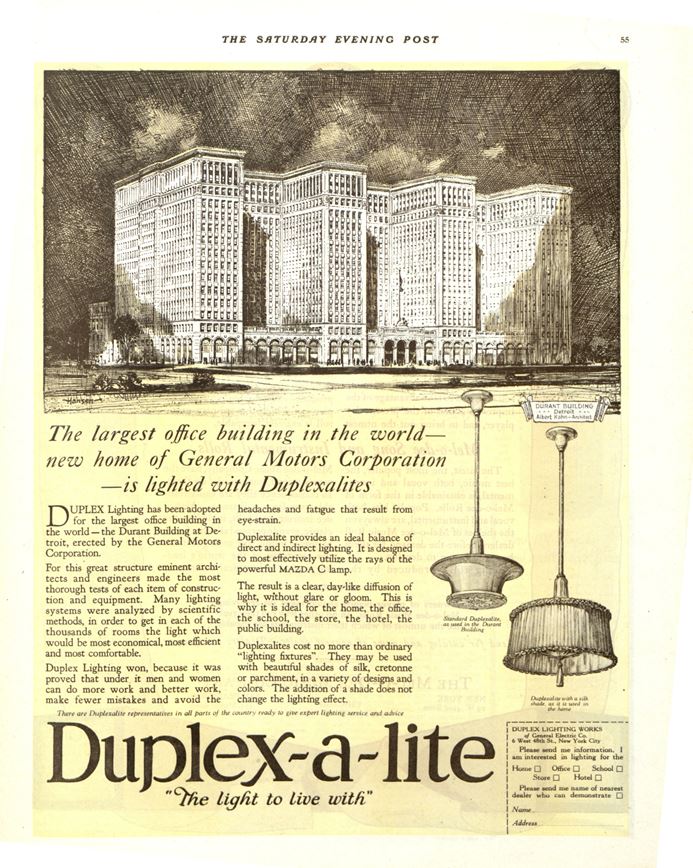

Soon enough, he caught the attention of Henry Ford, who asked Kahn to build a Model T plant in Highland Park in 1908. That began a 34-year business relationship between the two men that resulted in more than 1,000 completed projects for the Ford Motor Company. Kahn built the Crystal Palace in Highland Park and the River Rouge Complex (the largest manufacturing complex in the world at the time), and he began taking commissions from General Motors and Chrysler.

Kahn’s factories had a modernist appeal, but it wouldn’t have occurred to him to consider that at the time. He valued the function of his projects over their form, and, overall, he strove to keep costs down and meet his clients’ needs. Later in his life, he recalled: “When I began, the real architects would design only museums, cathedrals, capitols, monuments. The office boy was considered good enough to do factory buildings. I’m still that office boy designing factories. I have no dignity to be impaired.”

Last year, author Michael Hodges revisited Kahn’s life and work in his biography Building the Modern World: Albert Kahn in Detroit. Kahn’s factories in Detroit were instrumental in building bombers and tanks for World War II, but, as Hodges points out, Kahn also had a hand in bolstering the Soviet Union’s infrastructure. From 1929 to 1931, Albert Kahn Associates carried out a $2 billion contract to build 521 tractor, cement, and electrical plants in the Soviet Union from an office in Moscow. Like the factories in the U.S., these were converted for war production in the late ’30s. “In those years, he built the lion’s share, well over half, of the industrial capacity that enabled the Soviets to defeat the Nazis in World War II,” Hodges says.

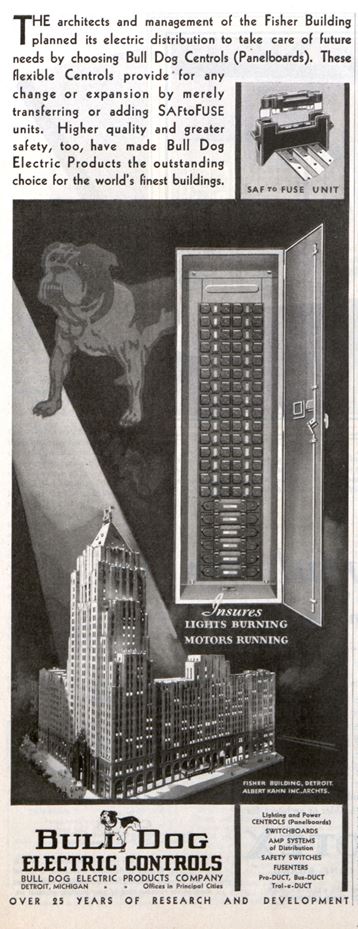

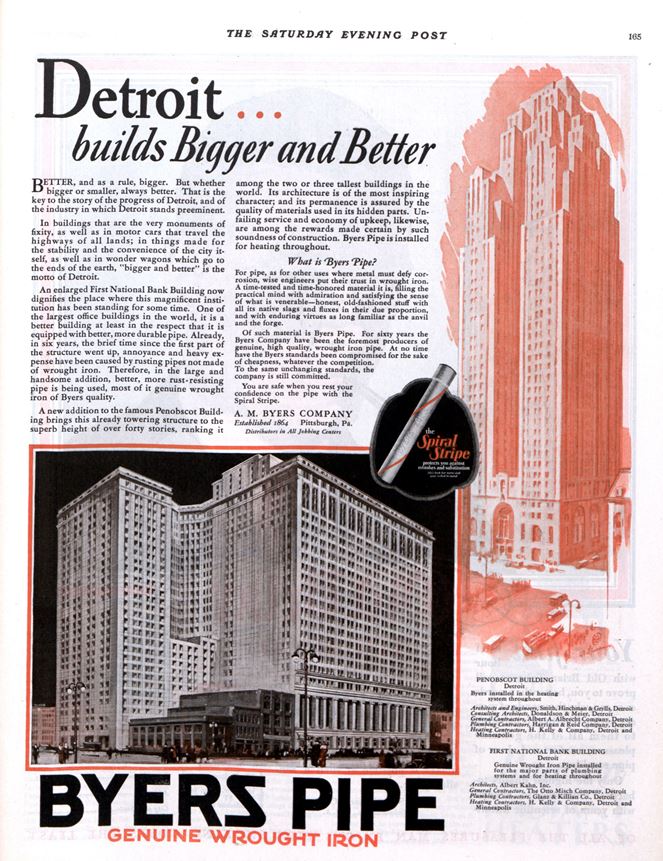

As well as being incredibly prolific, Kahn also proved versatile. His Fisher Building and S.S. Kresge World Headquarters grace Detroit with Art Deco style, and other works throughout his career showed Beaux-Arts and Neo-Classical influences. While his historic office buildings and homes are still treasured, many of Kahn’s factory buildings have not enjoyed the same fate. Since the city’s deindustrialization, many of the once-revolutionary buildings have become abandoned or demolished, like the Chrysler Jefferson Avenue plant and even the Crystal Palace.

Kahn died in 1942, still working, and without having seen the end of the war — an end his firm helped bring about. Two years before his death, he spoke to the New York Society of Architects, defending his philosophy of design: “The simpler the exterior the better it is, as a rule, for are we not quite agreed that a straight forward and direct expression of the function of the structure is an important element in all architecture, even the purely monumental; that proper proportions, effective grouping and good outline may be produced at no increase in cost; that these are infinitely more desirable than elaborate ornamentation, no matter how well executed.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now