Ever since the coronavirus began spreading across the U.S., the country has been left wondering what will happen next. When will it be safe to leave quarantine? When can the nation’s health and economy return to normal? And what will be the final toll on both?

Naturally, we look to the only other event in our modern history that bears any resemblance to this crisis: The influenza epidemic of 1918–1919.

In 1918, much of the initial news about the flu was disseminated by The Committee on Public Information, whose job it was to boost morale around World War I. They wanted to keep the news positive, and so the real devastation of the flu was initially minimized.

States and local municipalities were left to respond as they saw fit. St. Louis banned all public gatherings and shut its schools, movie theaters, pool halls, and taverns. San Franciscans were ordered to wear masks in public. Some towns denied entry to anyone without a signed certificate of health, and railroads wouldn’t accept passengers without them.

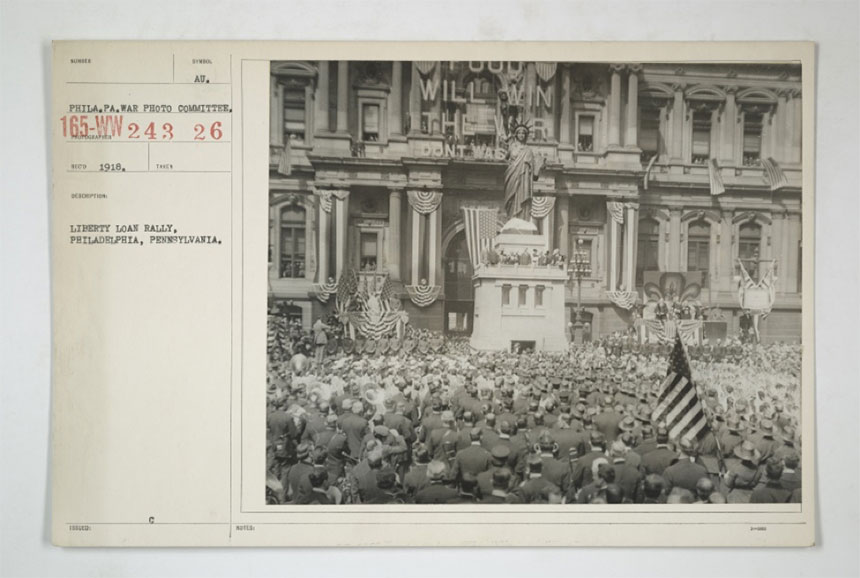

Philadelphia, on the other hand, held a Victory Bond Parade. Over 200,000 people attended. Three days later, every hospital bed in the city was filled. In less than a month, 11,000 had died.

Today, there is no shortage of information, but the messages are far from unified. Much as in 1918, some municipalities are choosing to chart their own course to “flatten the curve.” For instance, California issued a stay-at-home order and closed schools and non-essential businesses on March 19, while Florida did not issue a stay-at-home order until April 3 and has not closed non-essential businesses.

Then as now, civil authorities eventually recognized the importance of limiting contagion. In 1918, people were warned to stay away from crowds. Businesses, sporting events, and social gatherings were closed. In some areas, health departments passed out masks, prohibited stores from holding sales, and limited funerals to 15 minutes.

Fortunately, most Americans complied. The government’s campaign to build public support for World War I had created a public-minded spirit and a recognition for necessary sacrifice.

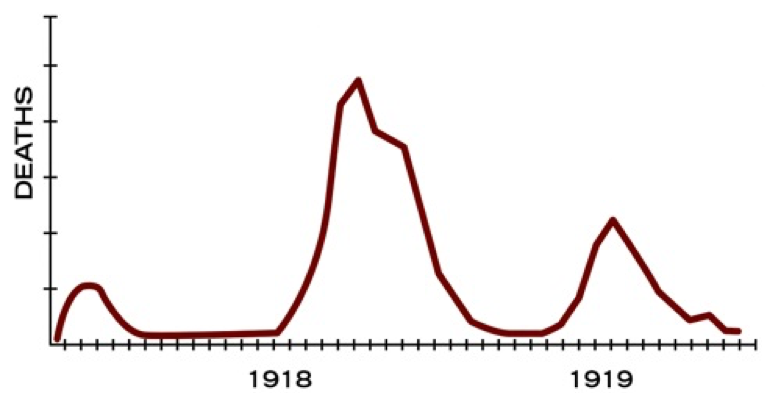

The 1918–19 pandemic arrived in America in three waves. In spring of 1918, the death rate for the first wave quickly rose, then fell to a low plateau where it remained for two months. Thousands of Americans died, but this was the mildest of the three waves. The next wave, which peaked in October, was five times more lethal. And by the time the third wave had passed, the virus had led to the death of 675,000 Americans.

It can be challenging to try and compare the two pandemics; there are many differences. One study in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimates that the case fatality rate from COVID-19 is 2.3 percent, but many factors make it difficult to determine. The 1918 flu’s mortality rate was estimated to be around 2 percent. Today, we have the advantage of modern medicine, testing, ventilators, and over a century of progress in providing care. But we also face the disadvantages of global connectedness, giving the virus easy opportunities to spread.

The coronavirus also targets a different population group than the 1918 flu. In 1918, the group most vulnerable to the flu were the heart of America’s work force: men and women between 25 and 35. Consequently, the life expectancy of younger Americans was shortened by ten years. Surprisingly, it was unchanged for 60- to 70-year-olds. Researchers believe older people probably had the advantage of immunity built up after exposure to the Russian flu pandemic of 1889–90. In contrast, this older group, as well as people with lung or immunity issues, are the most susceptible group to today’s virus.

Another difference appears to be the chance for delayed effects. Researchers believe the coronavirus will not be passed in utero between mother and fetus. In contrast, children in utero during the flu pandemic ran higher risks for many diseases such as diabetes, stroke, and mental illness. One long-term study found these Americans were 15 percent less likely to graduate from high school, and their wages were 5 to 9 percent lower than average.

But what about business and people’s livelihoods? In 2007, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published “Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Its Implications for a Modern-day Pandemic” by Thomas A. Garrett, who concluded that the economic effects of the 1918 influenza pandemic were largely short-term.

This is not to say the virus didn’t cause significant hardship. In Little Rock, Arkansas, for example, businesses irretrievably lost $10,000 a day on merchandise that couldn’t be sold later. Merchants reported a 40 to 70 percent drop in business. The retail grocery business was down by 30 percent, department stores by more than 50 percent. Only drug stores appeared to do well.

Garrett’s research also found that in Memphis, Tennessee, the worker shortage caused by the war was worsened by employees lost to illness. So manufacturing declined, and coal mining was cut in half.

The shortage of workers in 1918 forced employers to pay more to retain workers. Areas with higher mortalities showed greater overall wage growth.

A 2002 study by The Center for Economic Policy Research showed that the deaths of working-age adults in 1918–19 led to some of the business failures of the next two years, but the economy saw “a return to trend after this large temporary shock.” The sudden losses in stock value in 1918 were eventually recovered. The S&P 500 Index fell by 24.7 percent in 1918 but rose by 8.9 percent in 1919. The pandemic had “a surprisingly modest effect on the economy in 1919,” wrote journalist Kevin Drum in mid-March.

Despite predictions of stock market recovery, the economic impact of coronavirus will be different than the 1918 flu. For one thing, the economy isn’t benefiting from heavy defense spending as it did in World War I.

Another difference is that in 1918, small businesses were coping with a workforce reduced by illness, but were not closed outright. According to J.P. Morgan, about half of America’s 30 million small businesses can survive for just 27 days without new money. Service businesses, like bars and restaurants, have a margin of just 19 days without income.

Another difference is the cost of child care, which wouldn’t have been a concern in the day of stay-at-home moms a century ago. The Brookings Institute reports 25 percent of civilian workers have a child under 16 living in homes where no adult is present during the day. Closing all the nation’s K-12 schools for just a two-week shutdown would mean between $5.2 and $23.6 billion in lost economic activity. A four-week closing would cost up to $47.1 billion.

There was a short recession in 1918–1919, but it wasn’t severe. Businesses and governments took fewer sweeping measures to curb the spread of the flu; the economy benefited, but many more people were felled by the disease. For our current crisis, Forbes states there is a good chance for recession, both globally and in the U.S. The global economy, slowing before coronavirus, will slow even further.

Scientists, economists, and historians are doing their best to predict the outcomes from COVID-19, but, with so many variables, it’s difficult to imagine where we will be one month from now, let alone a year from now. One thing that hasn’t changed is our desire to help one another. For example, as Ben Railton noted in his recent article, in 1918 the Filipino Association of Philadelphia provided free medical supplies and treatment to Philadelphia residents who were ravaged by the disease. Today, Americans can still count on each other to help, and hope.

Featured image: U.S. Army / Oregon National Guard, via Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic, original image cropped

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

One thing seems to have held. Today, in April 2020 with COV-19, there remain in some places scoffers who refuse to observe the established protocol set by the CDC. We saw the terrible toll that took in Philadelphia’s 1918 influenza pandemic. Here in New Orleans our French Quarter is a ghost town and has been for over a month. Mardi Gras crowds were one reason we had such a heartbreaking infection spike, since no one at the time fully grasped what would follow. Ironically however, it seems the lessons of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 have taught this city how to cope, perhaps better than many. If nothing else, we know how to get back up and re-boot after a crisis. That said – this time around? Hand washing/masks/gloves/distancing are our new normal. And with every passing day it appears the curve is beginning to flatten.

I ALREADY HAVE THE “POST”

Jeff Nilsson is good at targeting past events. The delays politically to react were ever present in past history. With hope, maybe our governmental leaders in the future can be intelligent historians when pandemics surface in the future. The evidence was and is that when selfish and self centered politics emerge; then people suffer, and economies suffer for longer periods of time. As history repeats, the same mistakes and delays occur. Hopefully, our young future leaders will do a better job by reflecting upon the mistakes of our current leaders. There is always hope. Jeff Nilsson is insightful and figured it out. Great reporting!

Very informative! I certainly hope, though, that this doesn’t mean that we can look forward to a world-wide disaster every 100 years or so.