By the time World War II ended, America had paid a high price to stop men who rose to power through hatred and suspicion.

But then came Senator Joseph McCarthy and, with him, McCarthyism. The word wasn’t his invention. It first appeared in The Christian Science Monitor. It was a movement that created a culture of suspicion and mistrust, turned people against each other, and cost thousands their dignity, their jobs, and even their lives.

It’s all the more astonishing, then, that McCarthyism could almost be considered an accident, according to Larry Tye, author of Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy.

McCarthy had been elected senator from Wisconsin in 1946. In 1950, his re-election was threatened by past misdeeds catching up with him, including his violation of federal law by running for election while still serving in the armed forces.

His campaign needed a good cause to rally support. One of the top issues of the day was the housing shortage. The construction industry was slow to respond to Americans’ desire to buy a home in the suburbs.

The other issue was communism. Americans had long regarded the communist regime in the Soviet Union with mistrust and fear. No longer allies, the U.S.S.R. and America were entering a long cold war. Nations in eastern Europe were falling under Soviet domination, and the U.S. learned they had stolen our atomic bomb secrets.

Americans wondered why their country seemed to be falling behind the Soviets. Some politicians, like Congressmen Martin Dies, Carroll Reece, and Joe Martin, claimed it was treason by government officials who, they believed, were covertly working for the Soviets.

Republicans won big in the 1946 elections, largely on accusations of communist sympathies among Democrats. President Harry Truman had to show he was taking communist infiltration seriously. He signed an executive order that required millions of federal workers to take a loyalty oath. After 2.5 million employees had been checked, 5,450 went before a hearing and 5,118 were cleared. Of the 332 remaining employees, 102 were fired and the rest appealed their dismissal.

Amidst this atmosphere of suspicion, Senator McCarthy was scheduled to give a Lincoln Day speech to the Republican Women’s Club in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 9, 1950. According to Tye, he arrived with two speeches in mind; one addressing the housing shortage, the other communists in the U.S. government.

He chose the latter.

When he finished discussing the communist sympathizers in the State Department, he held aloft a piece of paper. According to the Wheeling Intelligencer of February 10, 1950, he said, “I have here in my hand a list of 205 [State Department employees] that were known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping the policy of the State Department.”

Tye states that, according to McCarthy’s executive secretary, there were no names. The paper, she said, was only the notes for his speech.

McCarthy was surprised at the enthusiastic response to his claims. Within a day, 33 newspapers had picked up the story of McCarthy’s list of names. Back in Washington, he repeated his charge but wouldn’t release the names. He claimed he wanted to avoid accusing any innocent parties.

What set McCarthyism apart from other demagogic tactics was this use of imaginary proof. Beginning with that list of names, McCarthy’s campaigns continually referred to confidential information that would expose communists in government — information he never fully shared.

Many reporters, as well as millions of Americans, were dazzled by McCarthy, his accusations, his crusade, and his theatrics. Few were willing to oppose his use of slander, innuendo, and baseless accusation to discredit and, in some cases, ruin men and women in government, for fear of being accused themselves.

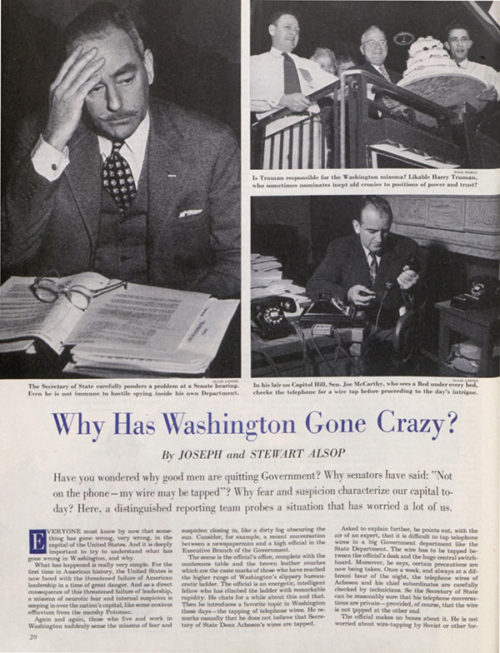

Among McCarthy’s few outspoken critics were Joseph and Stewart Alsop. On July 29, 1950, The Saturday Evening Post published their article, “Why Has Washington Gone Crazy?” They described a visit to McCarthy’s office on Capitol Hill, saying it was “like being transported to the set of one of Hollywood’s minor thrillers.

“McCarthy, despite a creeping baldness and a continual tremor which makes his head shake in a disconcerting fashion, is reasonably well cast as the Hollywood version of a strong-jawed private eye.”

Here the Alsops were hinting at the senator’s drinking problem, which would bring him to an early death.

A visitor is likely to find him with his heavy shoulders hunched forward, a telephone in his huge hands, shouting cryptic instruction to some mysterious ally. “Yeah, yeah. I can listen, but I can’t talk. Get me? Yeah? You really got the goods on the guy?”

The senator glances up to note the effect of this drama on his visitor.

“Yeah? Well, I tell you. Just mention this sort of casual to Number One, and get his reaction. Okay? Okay. I’ll contact you later.”

The drama is heightened by a significant bit of stage business. For as Senator McCarthy talks he sometimes strikes the mouthpiece of his telephone with a pencil. As Washington folklore has it, this is supposed to jar the needle off any concealed listening device.”

If the Alsops were not impressed, many voters were. They rewarded him with fanatical devotion, seeing him as the one, true American fighting communism. They made loyalty to McCarthy their principal measure of other Americans’ loyalty. Nye cites a report by pollster George Gallup: “Even if it were known that McCarthy had killed five innocent children, they would probably go along with him.” At one point, McCarthy was receiving 5,000 pieces of mail every day from supporters, many enclosing generous donations to his cause.

McCarthy could succeed in 20th century America because he claimed to have solid, specific evidence that would place statesmen or politicians at the heart of a vast conspiracy.

Not only could McCarthy make his case from minimal or nonexistent evidence, he could even use the lack of evidence to prove his point. If someone testified before McCarthy’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigation and refused to answer on the grounds of possible self-incrimination, McCarthy used this non-answer as evidence of the witness’s guilt.

McCarthy had many foes within Washington who pressed him to present his proof of treachery before Congress. McCarthy would always deflect the request, or respond with another accusation. Ultimately this proved his undoing.

In 1954, McCarthy was accusing the U.S. Army of harboring communists. A lawyer representing the army, Joseph Nye Welch, demanded to see the names of 130 communist or subversive workers that McCarthy claimed worked in defense plants, and he wanted it “before sundown.” McCarthy responded by slandering a young lawyer in Welch’s legal firm.

Welch couldn’t believe that McCarthy would assassinate the character of a promising attorney simply to deflect the demand. It was at this moment that Welch declared his famous rejoinder, “Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?”

Joseph McCarthy and Joseph Welch exchange words as Welch testifies before McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (uploaded to YouTube by AmericanExperiencePBS)

Welch told McCarthy that he would no longer discuss the matter and would not respond to McCarthy’s probing. “If there is a God in Heaven it will do neither you nor your cause any good.” He asked for the next witness and the audience broke into applause.

That same month, when Wyoming Senator Lester Hunt was working to curtail McCarthy’s powers, McCarthy threatened to expose the sex-crime arrest of his son. The Wyoming senator committed suicide.

The two incidents provided the evidence that the Senate could use against him. He was censured in December for abusing his power. A broken man, he died a few months after completing his term.

There was never a question that Soviet spies existed in America. But no solid evidence ever emerged that the treachery was what or where McCarthy claimed.

McCarthyism’s goal was never to root out Soviet agents in government. Rather, it was, as President Truman said, an issue of control, which Truman opposed. He had given in on the call to hunt communist employees in the government, but now he said, “I’m going to tell you how we’re not going to fight communism… We’re not going to try to control what our people read and say and think. In short, we’re not going to end democracy.”

And McCarthyism was never simply about one man. Said journalist Edward R. Murrow, “No man can terrorize a whole nation unless we are his accomplices.”

Featured image: Chief Senate Counsel representing the United States Army Joseph Welch (left) and Senator Joe McCarthy (right), at the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations’ McCarthy-Army hearings, June 9, 1954. (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Senator Joseph McCarthy was even more outrageous than I realized having just read this, and with some seriously deadly consequences. I love the picture at the top depicting sheer disbelief with McCarthy. Washington is America’s biggest freak show that’s bound and determined to outdo the entertainment industry in that regard, and with great success I might add!

I can picture in my mind, a similar (cartoon) illustration of ‘The Week’ news magazine of the current crop in a similar pose, looking at Trump. Should the depiction of Nancy Pelosi be one of her with egg on her face, or white powder under her nostrils?