What happens if a candidate-elect dies before inauguration?

What happens if someone refuses to leave office?

What if they literally lock themselves in there?

These questions might seem acutely relevant in the U.S., but they aren’t hypotheticals. Looking back to a Southern election that took place more than 70 years ago can offer answers, if not the answers anyone wants to hear.

In 1946, Eugene Talmadge ran to become governor of Georgia for a (nonconsecutive) fourth term. Though he had lost several recent bids for public office, the anti-New Deal Democrat was resolved to put up a fight to roll back the current progressive administration’s advances.

During his primary campaign, Talmadge traversed the state, performing a finely engineered rural persona and even promising, if elected, to act as a “minor dictator” for the benefit of farmers and sharecroppers. He also pledged to fight tooth and nail to somehow restore the legality of the state’s explicit “white primaries” — a Southern party tradition in which Black voters were excluded from the Democratic Party’s primary elections — fear mongering with grim predictions of war and unrest in Georgia if it were not to “remain a white man’s state governed by white men.” Talmadge openly enlisted Klansmen in Georgia to help his campaign while his opponent, James Carmichael, called for their dissolution.

In the July primary, to Carmichael’s 313,000 votes, Talmadge received only 297,000. But Talmadge won the nomination by “county units,” the determining measure of Georgia’s primary elections until 1962. His demagogic campaign’s laser focus on rural whites — not to mention a statewide crusade to purge Black voters from the rolls — allowed him to clutch the nomination. Absent a Republican challenger, Talmadge coasted to victory in the general election.

Then, a few weeks before he was to be inaugurated, Eugene Talmadge succumbed to cirrhosis complications and died.

The ensuing power vacuum generated a crisis of governance, equally complicated and moronic. As an unlikely circumstance intersected with a heated political atmosphere, the “Three Governors Controversy” bemused the nation and tested the resiliency of a state’s democracy.

Shortly after Talmadge’s death, Georgia’s opposing Democratic power brokers scrambled to sort out the extenuating circumstance in their respective favors. Quick to publicly announce his intention to fill the governorship was Herman Talmadge, the late Talmadge’s son and campaign manager in the recent election. The young Talmadge went on the radio to appeal to Georgia’s General Assembly, calling on lawmakers to assure “the platform [Talmadge] espoused be carried out,” and to vote to crown him governor according to his confident interpretation of the state’s recently-ratified constitution.

The young Talmadge’s seemingly bonkers claim to the state’s highest office was based on constitutional language from 1824, and his case rested on his having won some write-in votes in the general election. According to The Three Governors Controversy: Skullduggery, Machinations, and the Decline of Georgia’s Progressive Politics, a detailed account of the affair, a plan to secure write-in votes for the young Talmadge, as a sort of insurance policy, had been devised in the past year by an obscure shopkeeper and Talmadge fanatic in Monticello named Gibson Greer Ezell.

According to several accounts, Ezell, a political science minor, had convinced Herman Talmadge and his team — without the knowledge of the elder Talmadge — to run a furtive campaign for a small number of write-in votes so that the young Talmadge would be among the top two candidates in the unlikely — but ultimately actual — event of the Governor-elect’s death before inauguration. Ezell, it seemed, had read the state’s constitution in the newspaper one day and had recalled a paragraph that directed the General Assembly to elect the governor by voting between the two candidates with the most popular votes if one (living candidate) did not secure a majority.

The tabulation of write-in votes for an uncontested Georgia election in the ’40s was less than careful or precise, but it seemed that Herman Talmadge and primary candidate James Carmichael would come out on top, with a close third for a Republican tombstone salesman from Franklin County. Carmichael — likely recognizing his slim chances against the winner’s son in a vote by the legislature — said he would not accept the governorship.

But another man, M.E. Thompson, was interested, and he had an entirely different case for assuming the office.

Thompson was the state’s first lieutenant governor-elect, having won the first such election since the position was added to Georgia’s constitution the year before. He posited that he was the next in line for governor, even if the late Talmadge hadn’t yet been inaugurated. Thompson argued that it would be absurd for the General Assembly to nullify the — quite unambiguous — results of the election to seat a write-in candidate. The state attorney general agreed with him.

Also in agreement with Thompson was the sitting governor, Ellis Arnall, who had supported Thompson’s political ascent. Decidedly anti-Talmadge, Governor Arnall had presided over the barring of white primaries as well as the lowering of Georgia’s voting age to 18. In yet another interpretation of Georgia’s constitution, Arnall announced that he would not be vacating the governorship unless the lieutenant governor were to succeed him.

In the weeks leading up to the start of the General Assembly’s session in January, the two camps waged public campaigns to win over popular opinion. Talmadge roused his base with the same racist and anti-urban rhetoric for which his father had been notorious, making the survival of the white primary — a necessity for white supremacy — central to his appeal. Thompson then caved in to his opponent’s platform, vowing to conserve the white primary and even to introduce the county unit system to general elections and impose tighter voting restrictions. Whether he knew Thompson was bluffing or not, Arnall held that he would only step down after the lieutenant governor-elect was sworn in.

When the General Assembly convened, Atlanta was packed with Talmadge’s die-hard rural supporters, the “wool hat boys,” donning his characteristic red suspenders and causing a stir right on the chamber floor. Even after they were removed, the General Assembly remained a rowdy scene of heavy drinking, threats, and reports of bribery. Given the hard-line stances of each side, the legislature might have sided with Thompson, or with Talmadge, or called for a special election, depending on who could keep their adherents sober enough to vote.

By close margins, the General Assembly voted to “immediately elect a governor viva voce,” a motion that would begin tabulation of the write-in votes and surely end with a Governor Talmadge. But once the envelopes of county returns were opened and the write-in votes counted, Talmadge had come in third behind Carmichael and the Republican tombstone salesman. This would have barred him from eligibility, but, in time, a committee found 58 more votes from Talmadge’s home county of Telfair that put him over the top. He was sworn in as governor a little before 2 a.m.

The controversy was far from over, though. As promised, Governor Arnall stayed locked in his office when Talmadge walked over to claim it that night. Arnall refused to leave, even after Talmadge’s posse busted his door down and beat up his aides.

The disagreement over who laid rightful claim to the office (both the title and the physical space) escalated over several weeks. Arnall called Talmadge “the pretender” and struggled to maintain his duties, even as his “successor” changed the locks to the executive office, moved his family into the governor’s mansion, and enlisted the National Guard to keep him away from the state house. The two governors were both appointing staff, signing bills, and writing checks, like some real-life parody of government. The Federal Bureau of Roads held up millions of dollars in funds until Georgia could settle its dispute.

Arnall took to the radio, pleading to Georgians to express indignation to their representatives: “Georgia will lose its good name, its good reputation if we sit idly by and allow a military coup d’état, thugs and ruffians to take over the state government.”

Magazines and radio hosts all over the country couldn’t get enough of the state with two governors. Students and religious groups marched on Atlanta, decrying “King Herman the First” and hanging swastika’d effigies of Talmadge. Even as outsiders marveled at the state’s ineffectuality, they couldn’t necessarily agree on a solution. A New York Times editorial in January called on Arnall to, in effect, be the bigger statesman and step down for the sake of unity. The next week, the president of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare sharply rebuked the Times writer, opining that “Governor Arnall is fighting for democracy against one of the most sinister fascist threats that this country has yet experienced.” A column in this magazine from the same period questioned whether the label of “fascism” was right for the Georgia situation: “Why use foreign words for American miseries?”

In March, George Goodwin, a reporter for The Atlanta Journal, published some bombshell findings after digging through the state’s election results. In the records for Telfair County — the one Talmadge hailed from and that produced a magic number of winning votes for the General Assembly — Goodwin noticed some irreconcilable irregularities. The last 34 names on Telfair’s sign-in sheet, supposedly marked in the order of voting, were in alphabetical order. Upon further investigation, he found that all but two of them were either deceased, non-voters, long gone, or untraceable. Goodwin’s stories showed irrefutable voter fraud that happened to favor Herman Talmadge, and he won a Pulitzer Prize for local reporting.

Later that month, after 66 days of a pretend governorship, the Georgia Supreme Court ruled against Talmadge, nullifying his claim to the office as well as any actions he took while he occupied it. In a 5-2 decision, they decided that — in spite of the interpretation of Herman Talmadge’s Monticello advisor, Ezell — the state constitution did not give the General Assembly the authority to elect a governor. Talmadge swiftly vacated the office, and his appointees were paid with contributions from his supporters, since they were not entitled to state funds.

Thompson assumed the governorship, denouncing Talmadge for his “attempted seizure of the government by force and fraud.” The “Talmadgeites” promised they would have their reckoning.

The end of the “Three Governors Controversy” was hardly the end of the young Talmadge’s political career, however. He immediately announced his campaign for the coming 1948 election, and, after winning, held the governorship until 1955. Then he completed some of his father’s unfinished business, winning a Senate seat and holding it for more than 20 years.

In recounting the 1947 controversy, Talmadge made light of his undemocratic hijinks and denied knowledge of any voter fraud on his behalf. “People enjoyed politics then,” he told the Atlanta Journal-Consitution in 1996. “It was a form of entertainment.”

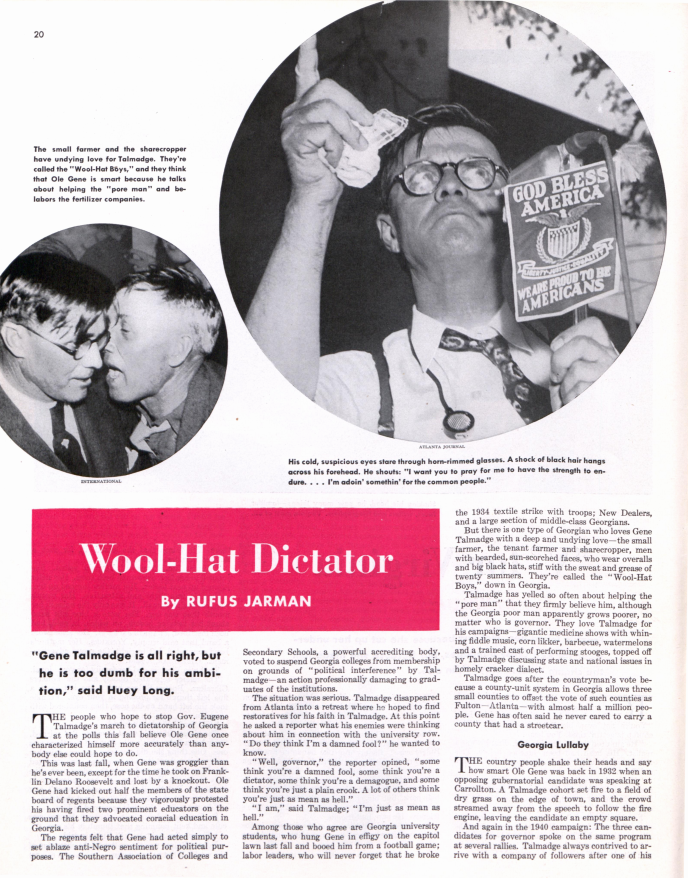

Read “Wool-Hat Dictator” by Rufus Jarman from the June 27, 1942, issue of the Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Governor M.E. Thompson taking power after the Three Governor’s Controversy, Atlanta, Georgia, March 24, 1947, LBCB103-054a, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, 1920-1976. Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now