This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks took her famous stand sitting down. Returning home after a long day of work at a department store, Parks was seated in the middle section of a Montgomery bus; under the practices of Jim Crow racial segregation, such buses had a movable sign that could designate certain sections “white” and others “colored,” and as more white passengers boarded the bus, driver James Blake moved the sign behind Parks’ row and demanded that she and other African-American passengers move further back. Parks, thinking (as she later reflected) of both her own numerous prior experiences of such mistreatment (including with Blake himself) and of the recently lynched Emmett Till, refused to move, and Blake called the police who arrested her for violating the city’s segregation laws.

In one of my earliest Considering History columns, I highlighted how Parks’s activism was interconnected with a communal effort by a number of Montgomery women to challenge the city’s history of sexual as well as racial violence, showing her individual choice was a part of something much broader. But Parks’s own life story likewise helps us recognize that one moment both as the product of many influences that brought her to that Montgomery bus and as part of a lifelong commitment to justice and equality that would last another 50 impressive years.

Born in 1913 in Tuskegee, Alabama, and raised on her maternal grandparents’ farm in Pine Level (just outside of Montgomery), Parks spent much of her childhood within two longstanding, prominent African-American communities. Her family were members of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, the historic African-American religious community that had been founded a century earlier in Philadelphia and that had produced the Charleston (SC) slave revolt leader Denmark Vesey among many other influential figures. Her mother, Leona Edwards McCauley, was a schoolteacher, and Parks attended a series of historic African-American educational institutions, including the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls and the Alabama State Teachers College (where Parks studied secondary education before dropping out to care for her ailing grandmother and mother).

These supportive spaces were not at all free from racial prejudice and terrorism, however. In a 1995 autobiographical piece in the Washington Post magazine, Parks remembered “staying up late” with her maternal grandfather “as he sat resolutely, shotgun at the ready, while the Ku Klux Klan rode the countryside” near the family farm. And the Montgomery Industrial School was burned twice by white supremacist arsonists, including one fire (in 1923) just a year before Parks enrolled there. But the school remained open and thriving, thanks in large part to its pioneering founder and principal Alice White, a figure who — like Parks’s grandfather — illustrated resilience in the face of such hate and violence.

In December 1932, when she was 19, Parks married a Montgomery barber named Raymond Parks, and he helped connect her to another historic African-American community: the NAACP. In 1932 the NAACP was collecting money across the state for its legal defense of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African-American teenagers falsely accused of raping two white women on a train in March 1931; Raymond helped lead that fundraising effort in Montgomery and introduced his fiancé Rosa to the organization. In 1943 she became the only female member of the Montgomery NAACP chapter, and soon thereafter she took on the important role of secretary for the chapter president Edgar Daniel “E.D.” Nixon. It was in conjunction with that role that Parks investigated the 1944 gang-rape of Recy Taylor, the case that began the community activism that culminated in the bus boycott.

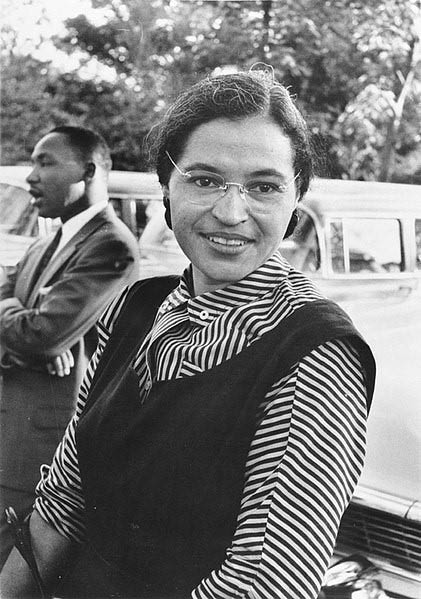

While Parks apparently took her 1955 stand entirely of her own accord, Nixon and the NAACP immediately supported her cause, bailing her out of jail that night and helping her mount a legal defense when she subsequently appealed her conviction and fine for disorderly conduct and violating a local ordinance. Both local and national leaders saw Parks as an ideal candidate for a test case challenging such laws; as the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. put it, Parks was “one of the finest citizens of Montgomery — not one of the finest Negro citizens, but one of the finest citizens of Montgomery.” Her unfolding case became a direct, visible corollary to the ongoing bus boycott (which lasted 381 days in total).

The case and its effects (which included both Rosa and Raymond losing their jobs) took a toll on Parks, and in 1957 she and Raymond moved, first to Hampton, Virginia (where she briefly worked at the Hampton Institute, a historically black college) and then to join her brother Sylvester McCauley and his family in Detroit. There Parks encountered the forms that racial oppression and segregation took in the north, including the housing discrimination that defined northern cities like Detroit in the period. She became a prominent leader in the movement to challenge housing discrimination, and through those efforts came to know the local lawyer and civil rights activist John Conyers, whom she supported in his first 1964 campaign for Congress. Once he was elected (the start of a 52-year congressional career) he hired Parks as a secretary in his Detroit office, a position she held until her 1988 retirement.

Parks’s work with Conyers in no way kept her from remaining an active participant in, and frequently a leader of, numerous fights for equality and justice across those decades. That included prominent local battles, including the aftermath of the 1967 Detroit riots, in the course of which the police killed three young men at the Algiers Motel (which Parks investigated as part of a “people’s tribunal”), and the rebuilding of her Virginia Park neighborhood (much of which had been destroyed as part of highway construction and “urban renewal” projects). And it included significant contributions to national campaigns, including efforts to secure the release of African-American political prisoners such as Gary Tyler, the Wilmington 10, and Joanne Little (a North Carolina woman who had used deadly force to resist sexual assault, and for whom Parks founded the Detroit chapter of the Joanne Little Defense Committee, which helped Little gain an acquittal).

Raymond passed away in 1977, and for the remaining decades of her life Parks rededicated herself to community activism and leadership. In 1980 she co-founded the Rosa L. Parks Scholarship Foundation, donating most of her speaker’s fees to a fund for college-bound high school seniors in the Detroit area and throughout Michigan. In 1987 she and her lifelong friend Elaine Eason Steele founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development, an organization that offers young people “Pathways to Freedom” bus tours of civil rights, Underground Railroad, and other historic sites across the country. In the 1990s she published two autobiographies, Rosa Parks: My Story (1992) for younger readers and the full memoir Quiet Strength: The Faith, the Hope, and the Heart of a Woman who Changed a Nation (1995).

Parks’s bold stand on December 1, 1955, was indeed one of those singular moments that helped change America. But Parks also led a life of influential activism, inspired by communities from the AME church to the NAACP and focused on efforts from housing discrimination to wrongful imprisonment to educating the next generation of activists. The best way to commemorate Rosa Parks is to remember every stage of her inspiring American story.

Featured image: Natata / Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Another fascinating article on a most remarkable American woman. It was no accident that Ms. Parks was on THAT particular bus at THAT exact time. It led to a lifelong odyssey of activism of equality and justice she was destined to take for the betterment of black Americans over the next several decades.

I appreciate the links included here as well. Most people only think of the bus incident itself regarding Parks and don’t know the rest of her story which is A LOT. Thank you for this feature Professor Railton.