Executive clemency wasn’t meant to be controversial. The Constitutional power to “grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States” was intended for acts of compassion.

In the Federalist Papers (no. 74), Alexander Hamilton wrote that justice could seem too cruel, too brutal if it never made exceptions for the “unfortunate” guilty. An act of clemency, he said, might “restore the tranquility of the commonwealth.” And since groups of men too often encouraged each other to be stubborn and harsh, “one man appears to be a more eligible dispenser of the mercy of government than a body of men.”

Since then, clemency have also been used to help the country move beyond political divisions. This was Gerald Ford’s intention in 1974, when he pardoned former President Richard Nixon for crimes stemming from the Watergate scandal. But many Americans felt the pardon was part of a political deal struck between Nixon and Ford. Most (54 percent) disapproved of the pardon, and Ford’s public approval fell from 71 percent to 37 percent by the end of the year.

Americans have come to suspect the pardoning of Nixon, “Scooter” Libby, Marc Rich, and others as politically motivated, sending the message that presidents are ready forgive illegal acts — lying to Congress, contempt of court, or illegal campaign contributions — that benefit themselves or their party.

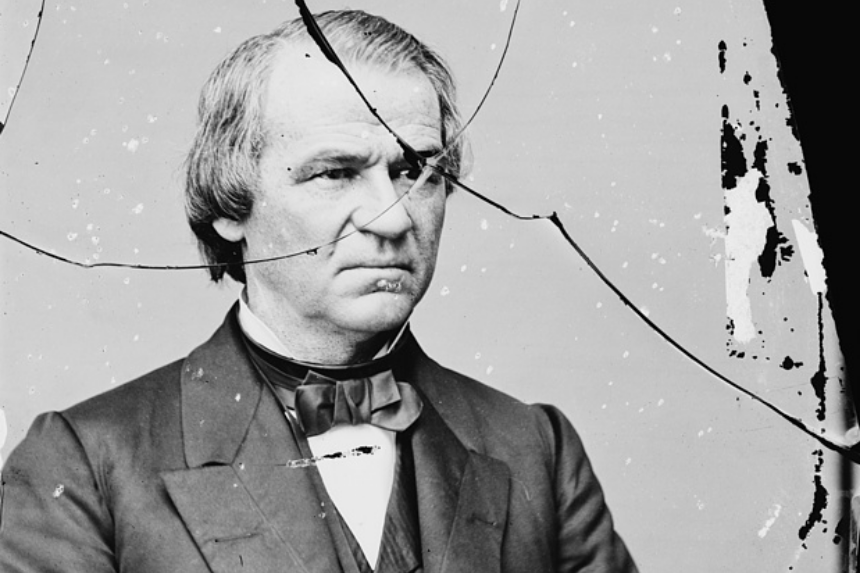

Ford’s pardon is now considered the most controversial in our history. But the post-Civil War pardons of President Andrew Johnson shocked the nation, galvanized his political opponents, led to his impeachment, and set back the cause of civil rights for decades.

When Johnson became president upon the death of Lincoln, he appeared to be continuing the program of clemency that Lincoln had suggested. But he soon grew even more lenient than his predecessor.

Johnson wanted the southern states to revive their economy and society, but he wasn’t ready to see former Confederate leaders resume their political power. So in May of 1866, he offered amnesty to all former Confederates who owned less than $20,000 in property, provided they took an oath of loyalty to the union.

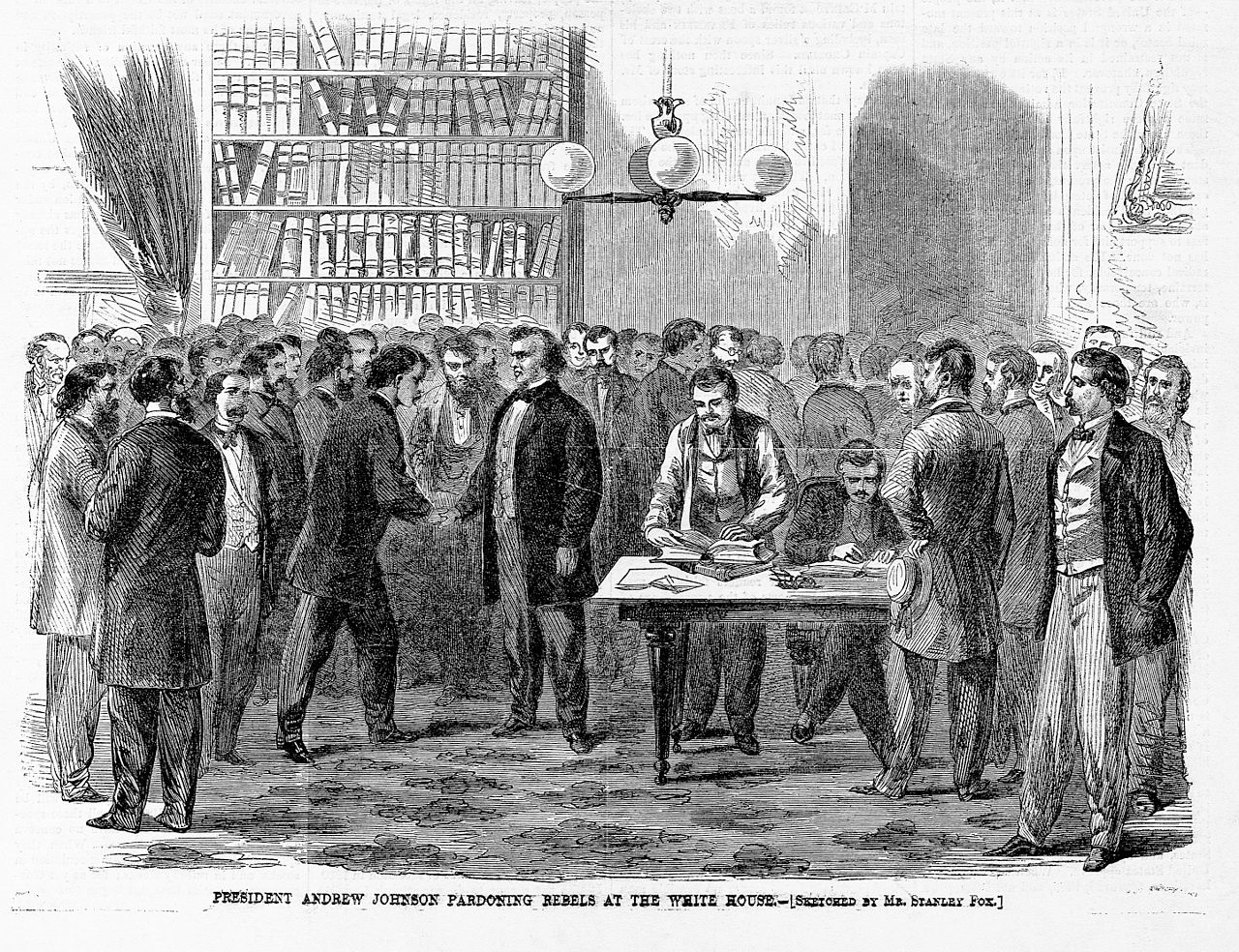

Southerners with more property would have to apply directly to the president for clemency., which he freely gave. This man who had grown up in poverty was flattered by the attention of leaders of southern society, and enjoyed granting them pardons. Said Ralph Waldo Emerson, Johnson couldn’t “resist their condescensions and flatteries.” Over the next two years, Johnson granted more than 13,000 such petitions.

A bigger factor, though, was Johnson’s belief that wealthy Southerners could prevent what he most feared: Black Americans gaining political power. “This is a country for white men,” he wrote, “and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men.” In his book, The Republic for Which It Stands, Richard White writes that when a delegation of prominent Black Americans headed by Frederick Douglass called on him in the White House, he was unwelcoming. He later said Douglass “would sooner cut a white man’s throat than not.”

A third factor in his 1866 clemency was his anger at the so-called “radical” Republicans. Unlike Lincoln and Johnson, they had kept their party affiliation instead of running as candidates of the National Union Party. They were focused on protecting the lives and rights of freed slaves, which Johnson, a former Democrat and still a slave owner, opposed. The Republicans became Johnson’s bitter opponents as they saw him offering pardons with no assurance former Confederates would provide civil rights for Black Americans. The Radicals angrily opposed blanket amnesties since they removed the only real leverage the federal government had to ensure the South honored African Americans’ rights.

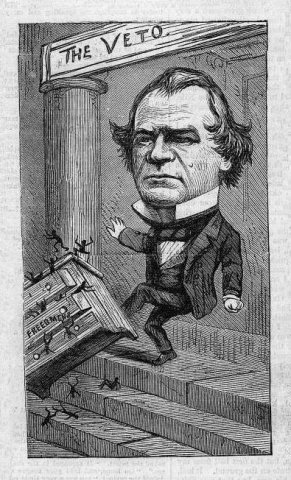

Johnson increasingly opposed Congressional actions to help Black Americans. He helped dismantle the Freedmen’s Bureau, which had been established to aid freed slaves. And he opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which would guarantee voting rights for African Americans and establish equal protection laws that superseded state laws.

He was lionized in the South, but increasingly resented in Congress, even among moderates. In response, Congress overrode his veto of the Civil Rights Bill and revived the Freedman’s Bureau.

Johnson also opposed the 14th Amendment, which made every person born in the U.S. — except Native Americans — citizens. It also extended the protection of civil rights and prohibited leading former Confederates from holding office. And it prevented Johnson from bringing southern states back into the union until they ensured civil rights for African Americans. Furthermore, Congress passed a law that prevented the president from firing members of his cabinet and choosing more supportive people without Congressional approval. (The law was repealed in1876, and a 1921 Supreme Court decision made it clear the president had complete power over the membership of his cabinet.)

Moderate Northerners viewed Johnson’s actions with growing alarm. While they wanted to see a speedy restoration of the union, there was a limit to their acceptance. They still wanted to see that the war had accomplished something, that thousands of their soldiers hadn’t died so the Old South could pick up where it left off. They wanted the South to acknowledge the end of both the Confederacy and all aspects of slavery.

Now they were outraged to learn of the “Black Laws.” Enacted in former Confederate states, the laws effectively bound African Americans to year-long contracts to work the plantations — effectively reviving slavery without using the name. African Americans who didn’t cooperate and left the plantations could be arrested for vagrancy and rented out to white planters.

Northerners were also angry to see former Confederate leaders being voted back into Congress. Northern legislators refused to seat them until their states had agreed on full reconstruction.

To build public support for his position, Johnson set out on a speaking tour across the country. Between praising his own accomplishments, he’d complain about the lies and insults directed at him by “a mercenary and subsidized press,” and the journalists who vilified him. He compared himself to Jesus, and the radical Republicans to Judas. He frequently wandered from his speech to angrily respond to hecklers. The speaking tour awoke little support. Instead, it stirred up angry crowds and confrontations between opponents and supporters that led to brawls.

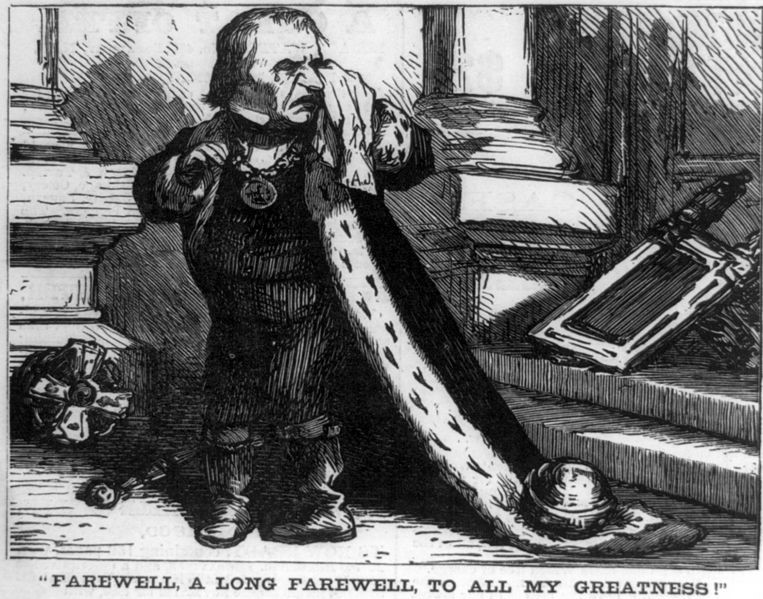

Congressional resentment of Johnson’s actions eventually reached the boiling point when, in 1867, Johnson fired one of his chief critics, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. The following year, the House impeached Johnson. He missed being convicted and removed from office by just one vote.

Now, as Christmas of 1868 approached, Johnson was in his final days in the White House. He extended his clemency to all former Confederates, restoring all their rights without requiring a loyalty oath. He spoke of the amnesty as an act of compassion and restoration of good will. It would, he said, “renew and fully restore confidence and fraternal feeling among [all southern people], and their respect for and attachment to the national government, designed by its patriotic founders for the general good.”

Southern newspapers were full of praise for the outgoing president. The amnesty gave the South reason to celebrate. But northern papers echoed the feeling of betrayal. And, as the Radicals had predicted, it robbed the federal government of its strongest incentive for the South to embrace reconstruction.

Andrew Johnson never regretted his actions. But, as Professor Elizabeth Varon has written, “He did more to extend the period of national strife than he did to heal the wounds of war.” And his determined opposition of equal rights kept Black Americans in poverty and kept racist politics alive to plague future generations.

Featured image: Andrew Johnson (Library of Congress)

Editor’s note: Paragraph 10 has been updated to better reflect Andrew Johnson’s lack of solidarity with Republican legislators.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

That certainly is a fine exposee of Johnson.

The history books I was read did not reveal all that,

but focused on his impeachment which was as

unjustified as that against our glorious Don.

What a mess with the first President Johnson a century earlier. Very shameful with his attitudes and actions toward everyone not a white male. Falling into that category myself doesn’t make me any less disgusted, condoning or forgiving of his actions more than 150 years later.

Having said that, it makes the current crashing downward spiral of the United States all the more treacherous and unforgivable with it arguably having the most hideously greedy, corrupt, sadistic government in the world. The industrial military complex loyalty overrides everything. Allocating billions for foreign countries with nothing for our own people in their darkest hours physically and financially. Annual U.S Defense spending, $740 billion. TEN other countries around the world, $726 billion COMBINED.

A Speaker of the House so dysfunctional as to declare “nothing is better than something”. They’ve kept their word on THAT, for months and months. Whatever could be done at this point is too little too late to keep the $#)+ from hitting the fan very soon. The die has been cast for the U.S. for years to come by adult pre-schoolers. Worse, because the average 4 year old would have logic and compassion these people don’t, and will never have.