Deas Island Park is a scenic spot on the Fraser River in Delta, British Columbia. The park is popular with those seeking quiet moments amid the poplar trees, tall grasses, and riparian walking trails. A solitary Queen Anne Revival-style house sits facing the river. Nearby, a plaque is all that remains of the once bustling salmon cannery that existed here 150 years ago, stating that it had been operated by a “free Black tinsmith named John Sullivan Deas.”

John Sullivan Deas was born in Charleston, South Carolina. Trained as a tinsmith in his teens, he found work in San Francisco in the 1860s as the California Gold Rush waned. In spite of his standing as a free Black man, the Fugitive Slave Act made his situation precarious. Enacted to return former slaves to their owners, the legislation often resulted in claims and seizures of free Black people living in free states like California, despite little to no evidence they had been enslaved. In addition, California did not allow Black people to vote or participate in juries or civil processes.

The British colony to the north, headed by governor James Douglas, himself of mixed European and African ancestry, offered security and encouragement to free Blacks to emigrate. Douglas promised that after seven years, landowners swearing allegiance to the Crown would be granted full civil rights.

Deas made his way to Victoria on Vancouver Island in 1862. He later married Fanny Harris from Hamilton, in what is now Ontario, and they had eight children together.

In 1870, after several business ventures in Yale and Victoria, Deas contracted to make cans for Edward Stamp’s salmon cannery venture on the B.C. mainland, one of only two in operation that year. Stamp was an English ship captain interested in canning and exporting the plentiful salmon of B.C.’s west coast. Stamp died within a year, and Deas went into the salmon canning business for himself.

“The period from the 1870s to 1890s is often referred to as the Salmon Rush,” notes Mimi Horita, Marketing and Visitor Services Manager at the Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site in Steveston, British Columbia. “Deas and his competitors mined for the ‘red gold of salmon,’ fishing the seemingly unlimited resource and canning it for export abroad to the United Kingdom.”

In 1873, Deas acquired the island that would one day bear his name and set up a large-scale industrial project. He constructed a wharf, outbuildings, warehouses, and living quarters over seven acres. He was the face of the operation; he owned the land and the buildings, and his name appeared on the cans of salmon that he exported.

As a result of its ideal location in the early years of the industry before Steveston canneries were established, the Deas Island Cannery was briefly the largest salmon producer on the Fraser River. Depending on the salmon run, the production could amount to between 200,000 and 400,000 cans per year. For the 1872-73 season, Deas’s pack was twice as large as any other cannery.

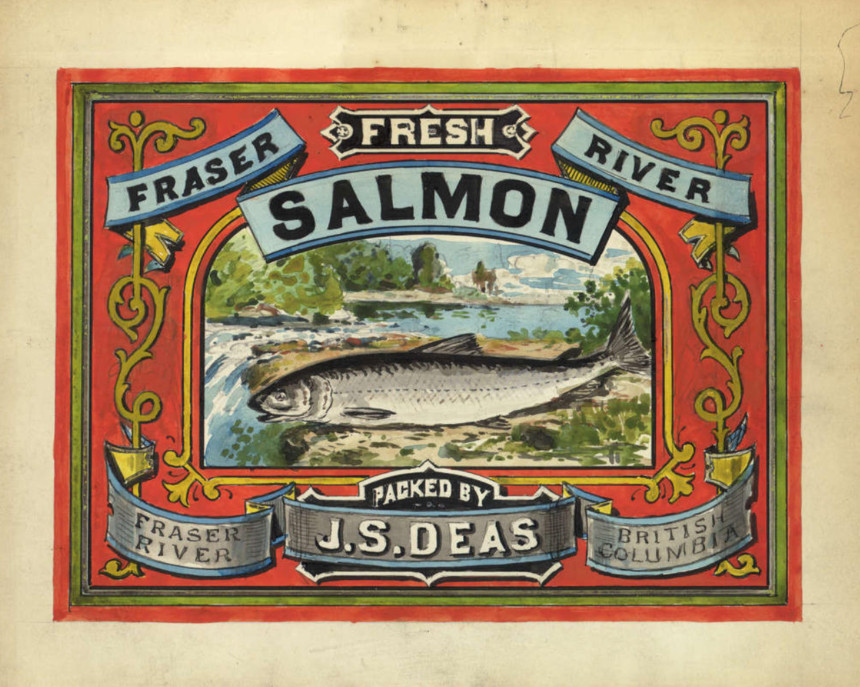

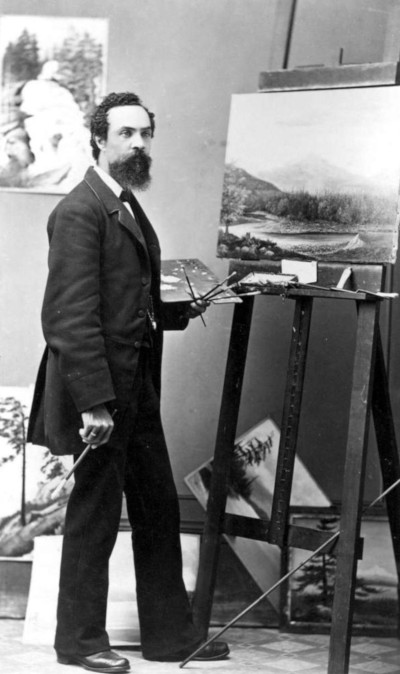

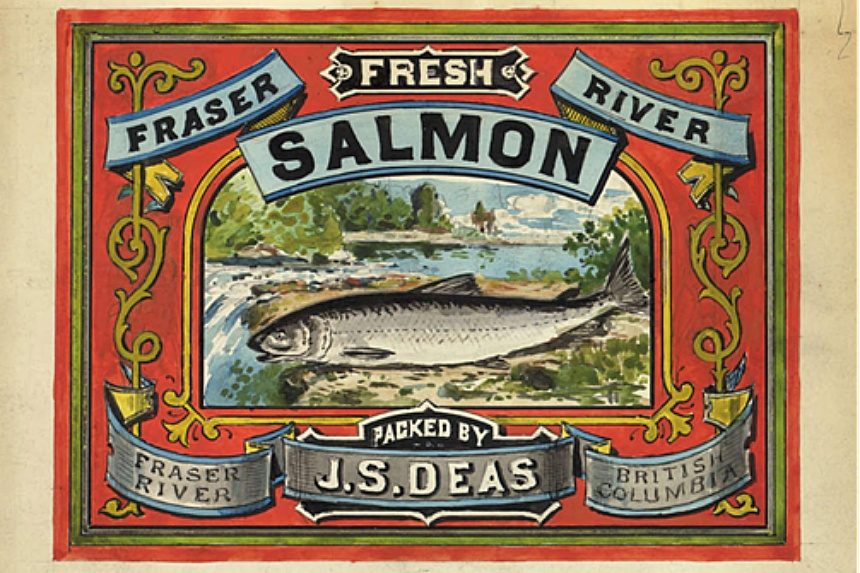

Deas commissioned a fellow Black American, artist Grafton Tyler Brown from San Francisco, to design striking artistic labels for his canned salmon products. Brown was the first Black artist working the Pacific Northwest, and later lived and worked in British Columbia as a professional artist, painting panoramic views of towns and the homes of prominent citizens.

Despite Deas’s early success, the next four years saw increasing land encroachment and competition for profits and for the precious runs of salmon, the numbers of which fluctuated wildly between seasons. When his attempts to secure exclusive drift net rights adjacent to his cannery were denied by the Federal and Provincial governments, Deas sold his business in 1877 to the BC Canning Co., which operated the site until its closure in 1909. His family purchased a home in Portland, Oregon, and moved back to the United States.

In July 1880, Deas died suddenly at age 42. While the cause of his death remains unknown, it was speculated to be due to his former toxic occupation of tinsmithing.

While Deas was engaged in salmon canning for only a brief period of time, he was a unique figure. Author H. Keith Ralston said of Deas, “seven seasons in salmon canning during the first decade of continuous operation on the Fraser River entitle John Sullivan Deas to a prominent place among the founders of the canning industry in British Columbia.” Deas was one of the first Black entrepreneurs to establish a business of his own in the province, and his success represents a prominent example of Black entrepreneurship in the pioneer history of British Columbia and Canada.

Featured image: Deas Cannery Label (Image I-61591 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for this interesting article on John Sullivan Deas. I never knew much about the commercial canning industry up in Canada, other than of its importance. I’m sorry to hear he died at such a young age with so much more to live for, not to mention his family.