From blizzards to hurricanes, the storms that start on Earth can be bad enough. Though our ability to predict those events has gone from non-existent to fairly accurate, knowing that something is coming and being adequately prepared for it are two different things. That brings us to another natural phenomenon: a geomagnetic storm. Triggered by events in space, these storms disrupt our planet’s magnetic field. For three days in 1921, the most powerful geomagnetic storm to occur in the 20th century disrupted radio waves, caused fires, and wreaked havoc on the telegraph system. Looking back at the events of 100 years ago raises one unnerving question: what would happen if a storm like that hit today?

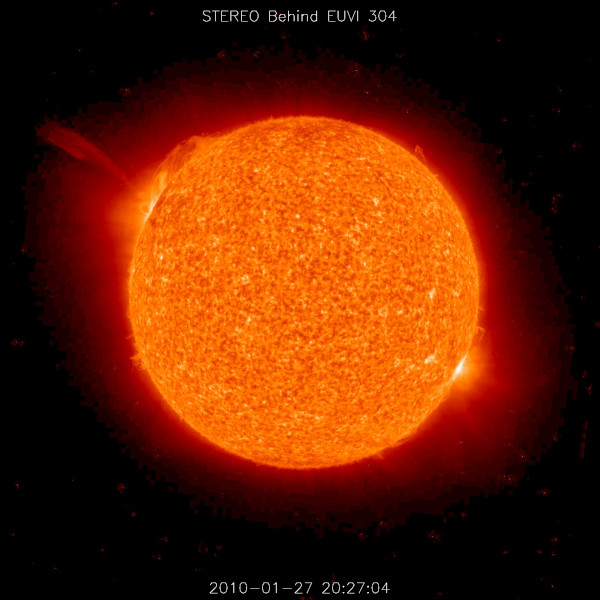

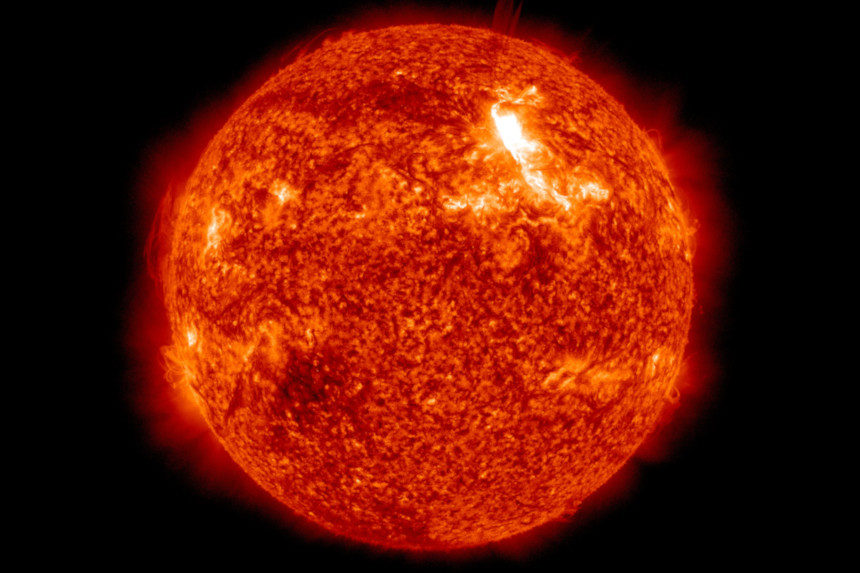

A geomagnetic storm originates on the Sun. You might be familiar with solar flares, which manifest to us as quick extra brightness on the Sun’s surface. These flares will often be accompanied or followed by something called CMEs, or Coronal mass ejections, which is a burst of plasma and magnetism released after the flare. This energy can travel millions of miles to affect the Earth’s magnetic field. Two major instances of this were 1859’s Carrington Event and the 1921 Geomagnetic Storm, which ran from May 13 to May 15.

The Carrington Event was named after astronomer Richard Carrington; he and Richard Hodgson documented a solar flare that produced a huge CME. On September 1 and 2, the telegraph systems in Europe and the U.S. fell into disarray. Some just stopped working, and other systems repeatedly shocked operators. A few operators reported that they were still sending and receiving messages with the power supply unplugged.

The effects in 1921 were even worse, thanks to the increased pervasiveness of commercial electricity and electrical systems in use around the world. The uptick in electrical current sparked fires, including the “New York Railroad Storm,” which was a fire near Grand Central Terminal. The CME created lights in the sky that echoed the Aurora Borealis over parts of the United States, notably in the northeast.

The telegraph system faced serious disruptions; first it slowed, and then completely stopped on May 14. Fuses in a number of telegraph systems blew or quit working altogether. The transatlantic cables that run underwater were affected in the same way as surface lines. And while the United States got the bulk of the visuals in the sky, the telegraphy problems extended all the way to Europe.

Since then, we’ve had a pair of major geomagnetic storms and one near miss. A 1960 storm dramatically affected radio around the world. The March 1989 event knocked out electricity in Québec, Canada for nine hours. Communications disruptions were reported all over the world. Satellites encountered any number of problems. The Space Shuttle Discovery was in the middle of a mission, but fortunately it only experienced some sensor malfunctions that righted after the storm passed. Another storm that August actually shut down the Toronto Stock Exchange. The near miss happened (or didn’t) in 2012. Because of the position of the sun, a huge CME missed Earth, which was nine days out of the orbital window during which it might have hit.

The frightening thing about a geomagnetic storm hitting Earth now is as plain as the phone in your pocket. Obviously there was radio and electricity in 1921 (and 1989, of course), but our lives have become so dependent on a vast layer of interconnected communications equipment that a geomagnetic storm could be a literal disaster. Cell phones, internet, and television are heavily reliant on satellites. Many of our largest cities function on outdated or overworked electrical grids, and our computer networks are also simultaneously dependent on those grids.

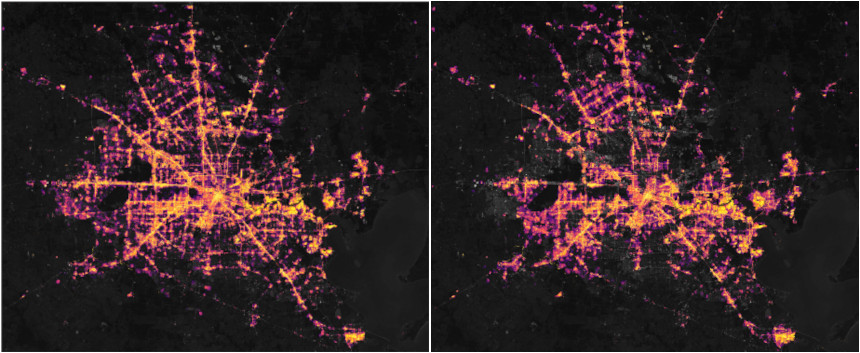

Matt Brady of thescienceof.org offered that a good point of comparison to what a big geomagnetic storm could do today might be what happened in Texas during Winter Storm Uri earlier this year. During February, the winter storm proved too much to bear for the infrastructure that handled electricity for the state. Over 4 million homes lost power. And power loss doesn’t just mean you sit at home in the dark; power loss disrupts communication, business, and personal environmental controls, like heating and air conditioning.

The lingering question is: how do you prepare for an event of this nature? The National Weather Service actually provides some guidance for this under Extreme Solar Event preparedness. Most of their tips are clever or common sense ideas about taking care of your own home or compensating for a loss of usable technology. On a macro scale, the best thing that the U.S. can do is to continue to closely monitor solar activity and be prepared to deactivate systems to protect them during a disruption; NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory is tasked with such observations of “space weather.” It’s also critically important that the outdated electrical infrastructure of the country be improved, as newer systems can handle such crises more readily that other systems that are decades old. With any luck, early warnings and quick actions would protect us from any lingering disruption. On the other hand, a little quiet time with a good book and a flashlight never hurt anybody.

Featured image: A 2012 solar flare (NASA.gov, courtesy of the Solar Dynamics Observatory; Public domain)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Dear Editor:

The story on the “Sun Storm” of 1921 caused havoc on the Canadian Pacific Railway, and, the C.N. R. here in Peterborough as telegraph and telephone service was intermittment, and, made it difficult to communicate

with trains and train movements for those three days.

Can not say if it was a problem nation wide, that would take a lot of intense researching.

Sincerely.

Gord Young

Peterborough ON

The more technology we have, the worse such a catastrophe would be now and in the future. Unfortunately today we have hackers (in addition to nature) that can create such situations to intentionally cause equally bad/worse chaos and misery worldwide.