When Linda Cozby (soon to be Wertheimer) — a Wellesley scholarship student graduate who still missed the enchiladas of her native New Mexico — got a minor job at New York radio station WCBS in 1969, she was happy. She had long wanted to be in broadcasting, and, “as a self-described flat-chested brainy ‘dark’ woman who didn’t wear makeup,” she realized that radio, rather than television, fit her. But when she saw how the two “brave, aggressive, ferocious” on-air women reporters at WCBS often had their stories taken away from them and given to men, she became dismayed. She realized that “tenacity and fortitude alone weren’t enough” in the business, writes author Lisa Napoli. “For women to get the jobs they desired, much less the respect, seemed an elusive dream.”

Wertheimer, of course, became one of the formidable female stars of National Public Radio. She directed and was a special correspondent on its magazine show All Things Considered and went on to cover politics. Her experience of radio industry sexism was much like that of the other three women who are featured in Napoli’s timely and quite wonderfully written new book, Susan, Linda, Nina & Cokie: The Extraordinary Story of the Founding Women of NPR. Those women are: Susan Stamberg, who hosted All Things Considered for many years, with warmth and brio; star reporter and personality Cokie Roberts, who was glamorous and down to earth (a tough trick to pull off) and who tragically died of breast cancer in 2019; and Supreme Court reporting eminence Nina Totenberg (she broke the story of Anita Hill’s allegations against Clarence Thomas). All found their chance at a “marginal and bedraggled” 1971 start-up where they could move up.

The four felt as much like friends as broadcasters. They were friends to us, whether listeners or guests — “Susan Stamberg was, like her voice, full of warmth, wisdom, and humor,” says advertising writer Barbara Lippert, who appeared on her show. “The exchange became a conversation among friends rather than a standard interview.” And they were friends to each other in every way, from the feminist spirit they developed — Linda and Susan Xeroxed copies of the brand-new magazine, Ms., together in 1972 and talked of the “revolutionary” publication on the air — to the protective camaraderie they quickly formed: “When Cokie walked in the door for an interview” at NPR in 1977, “Nina and Linda were there to cheerlead her on, and a mutual admiration society immediately formed,” says Napoli.

A former reporter and back-up host on of American Public Radio’s Marketplace (after working at the New York Times and MSNBC) and the author of three other books on media, Napoli is talking to me by phone from near her home in downtown L.A. She wrote the vigorously reported book during COVID, quarantining at her mother’s house in Florida, in one crazy, intense 18-month-long slog. “It wrung me out!” she says. “But I absolutely love this research — digging into history and rooting out facts and people and materials, and stitching it together to make sense in new ways. I was lucky to find enough people, and most of course were happy to talk to a curious stranger during their lockdown.”

Good that they did.

Tracing the journeys of these female radio pioneers of a certain age — Roberts was 75 when she died, Stamberg is 82, Wertheimer is 78, and Totenberg is 77 — was a gold nugget hiding in plain sight. Having written myself about the stubborn difficulty of mostly younger women advancing in network TV from the ’70s through early aughts in my book The News Sorority, I nodded along when I read Napoli’s quote from a male radio executive in 1964: “Many women may be fine in everyday conversation, but put them in front of a microphone and… they become affected, overdramatic, high-pitched. Some turn sexy and sultry.” How similar this is to the terser dictum I quoted from a TV network executive in 1970: “Audiences are less prepared to receive news from a woman’s voice.” It always seemed odd to me that in a field full of Ivy League-educated (i.e., supposedly enlightened) folks, there was such a hold-the-line policy on women; and the different machinations women had to go through to achieve their great success was instructive to me. Having those hurdles to buck made them better. Says Susan Zirinsky, until just recently the president of CBS news, “I thought of them as the first all-female army. They were out there, reporting historic stories, with impact. They were all at the top of their game. No one could match them.”

Napoli finds the same thing. She reports that “time and time again,” all four of the women found, in their job searches, that “there were no jobs for women or the company already `had its women.’ The women realized early on that they had to be twice as good and to work twice as hard as men to even hope to be taken seriously. Quickly this gave them a decided advantage” when they found a welcome place. In 1971, at the new — and enlightened — Corporation for Public Broadcasting-funded NPR president Bill Siemering wanted inclusiveness — and he wanted good hires, regardless of gender. Linda, newly married to the lawyer for a Congressman from Massachusetts, and Susan, married and the mother of a child, were hired. Nina and Cokie came later.

Although we easily think of them collectively, “They were so different from one another!” Napoli says. “If you were to look at anyone in mass media today, most of them come from pretty well-educated families.” Napoli noticed this in her own work. She says, “As the Brooklyn-raised daughter of a mother who was one of nine children and never went to college, the other staffers seemed to come from wealthy, coastal-elite families.” But whereas Nina — raised in Scarsdale, New York, outside of the city: the daughter of a renowned violinist — and Cokie — the daughter of Louisiana congressman Hale Boggs and his tony wife, Lindy, who took over her husband’s seat when he was lost in a plane crash in 1972 — came from a privileged upbringing, Susan — the daughter of a salesman who never went to college, on the then-ungentrified far Upper West Side of Manhattan — and Linda — a grocer’s daughter from New Mexico — did not.

They all went on to elite colleges. Susan (last name then: Levitt), attended Barnard on scholarship. Linda was on a full scholarship at Wellesley, where the Eastern girls made fun of her southwestern twang and her tacky dyed-to-match sweaters and skirts. The college was also the alma mater of Cokie. Nina attended Boston University, but didn’t graduate. But they weren’t self-proclaimed feminists from the get-go, Napoli stresses; in the mid-’60s very few women were. “It’s hard to convey to much younger women today. You look at Amanda Gorman; at 22 she wants to be President! — that, back then, just because you went to Barnard or Wellesley you weren’t expected to go out and blaze trails!” After all, Wellesley offered a Marriage Lecture Series. “Achieving professionally might be important, but equally so was how to snag the right man to ensure one’s future. I think most people would be surprised, as I was, that Cokie Roberts didn’t graduate from college gunning for a big career. Her main ambition was to get her boyfriend [New York Times reporter Steve Roberts] to marry her. She said she was `not even slightly’ a feminist at the time. And while I knew that Nina didn’t have a legal background, I didn’t quite grasp that she’d dropped out of college,” says Napoli.

Still, love for news and radio and broadcasting had hit them early. Susan had “worshipped at the altar of her family’s Emerson Bakelite Radio” and later concluded that “the absence of the visual was what made the medium a rich stimulant in her mind…. a thrill[ing] socially permissible form of eavesdropping…. like the salon she’d been dreaming of hosting since high school,” Napoli writes in her book. And back in Carlsbad, New Mexico, Linda listened to glamorous pioneering radio and TV reporter Pauline Frederick, who had advanced from reporting “How to Get a Husband” to covering the United Nations, where she was a star reporter. “Look, Mom, a woman!” Linda effused when the Frederick came on the screen — and she was inspired.

Throughout the book Napoli alternates the precise development of the women’s lives and careers with the development of public radio, key events in U.S. history in the change-powered 1960s and ’70s. The chapters on Cokie are perhaps the most attention grabbing because of her glamorous family, the drama that ensued when she (a devout Catholic) fell in love with Roberts, who is Jewish, her father’s disappearance and presumed death, and her depression when she was turned down for serious jobs until she landed print and broadcasting work that led her to NPR.

Even though this is a celebratory book, “the hurdles are not entirely gone today,” Napoli says. “And they never will be, because ageism is impossible to combat, especially when it’s masked as budgetary cut-back — even when we’re talking about radio, where the ‘look’ isn’t a matter of public record. NPR itself has a history of letting people go who are older (as does everywhere else, for that matter.) Linda had that experience when she was moved out of the hosting seat, though of course it wasn’t described as her ‘aging out.’ There was a major staff lay-off where much of the personnel downsized were over 50.”

The most touching scene in Napoli’s book, which also sums up its virtue and the lessons it carries, is actually in the first chapter. Cokie Roberts is dying, and Nina is one of her last visitors at the hospital. The two decades-long friends and colleagues look fondly at each other.

Nina’s parting words to Cokie are: “I’ll see you on the other side.”

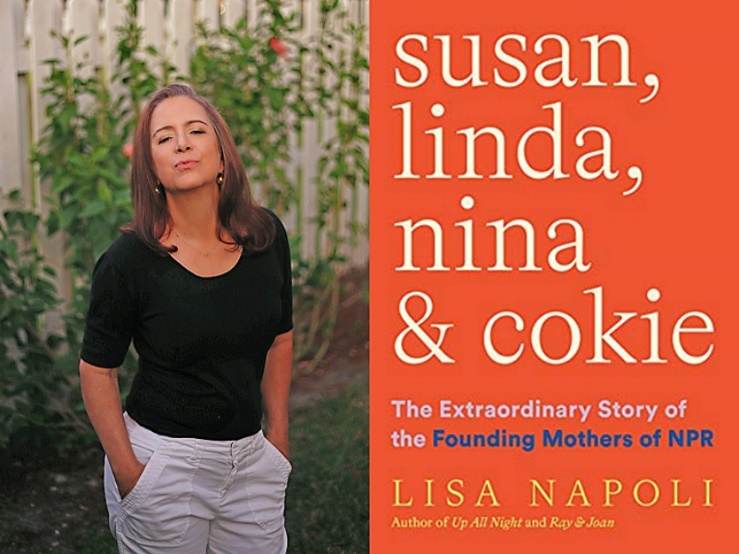

Featured image: Lisa Napoli (courtesy of the author) and her book, Susan, Linda, Nina & Cokie: The Extraordinary Story of the Founding Mothers of NPR (Abrams Press)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Very interesting article, Ms. Napoli. I really hate the fact women have had to go through so much hell of aggravation and degradation to get the positions they’re totally qualified for (often more so) than the men who got theirs in many instances just because they were women, and have excelled beautifully!

The male radio executive’s comments from 1964 are very inaccurate, sexist and dated of course. Unfortunately what he said probably reflected how most men in the business felt at that time, and possibly some non-progressive women too. The good part of that is he put it out there, and it likely helped women trying to break into this business know what the perceptions were, and prove them wrong, which they did

I think the fact that we’re more of a ‘gender-neutral’ society in general has been a good thing. Any man who acts overly manly or ‘macho’ is going to be perceived negatively by both men and women today. A woman who acts overly ‘feminine’ is also going to be perceived negatively by both sexes too. Both are antiquated oddities that seem strange, if not comical.

Since television news is a medium of sight and sound, this is even more acute. On the CBS Evening News, you take Norah O’Donnell just as seriously as you would Lester Holt or David Muir. She’s a current example of a woman who’s incorporated her femininity into a gender-neutral context, just as the men have with masculinity.

ABC’s Chief Global Affairs correspondent Martha Raddatz is a perfect example of putting herself in some scary places and situations as needed for the all-important news story. A job most men would wash out in. I dare anyone not to take her seriously. Sunday night World News anchor Linsey Davis is one of the few African American women to be such a high position. Smooth as silk, she’s comparable in every way to Saturday night (white) anchor, Whit Johnson.

Ageism in the broadcasting business and otherwise needs to be eliminated as a factor or excuse in letting someone go, which affccts both men and women in and out of that business. I know people born in 1975, ’76 that have been let go from an existing position or not hired for another due to their age. Yes. people 45, 46 are NOT too young to be experiencing this, even though I feel they are. It’s discrimination too. A lot of hurdles have been overcome, but there are always new ones and stubborn old ones that must continually be dealt with.