Mannequins that were used to sell fashions have been around since the 1400s. Back then, they were doll-sized and used to show well-heeled customers in Europe what the fabrics would look like. A few centuries later, the dolls had grown life-sized and were made of wicker, then wire, then wax. The wax mannequins were the most lifelike, but could melt on a hot day.

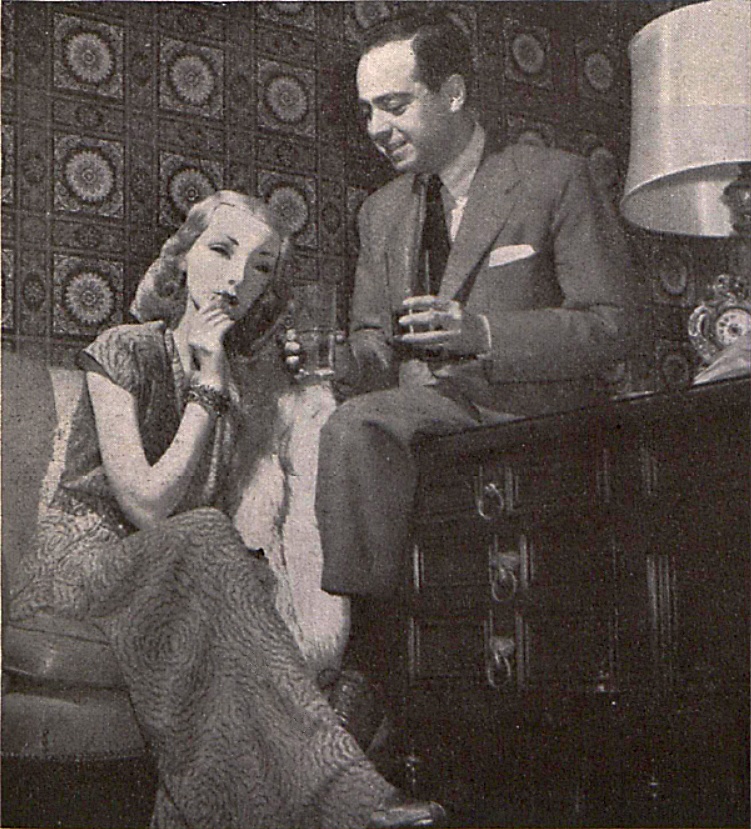

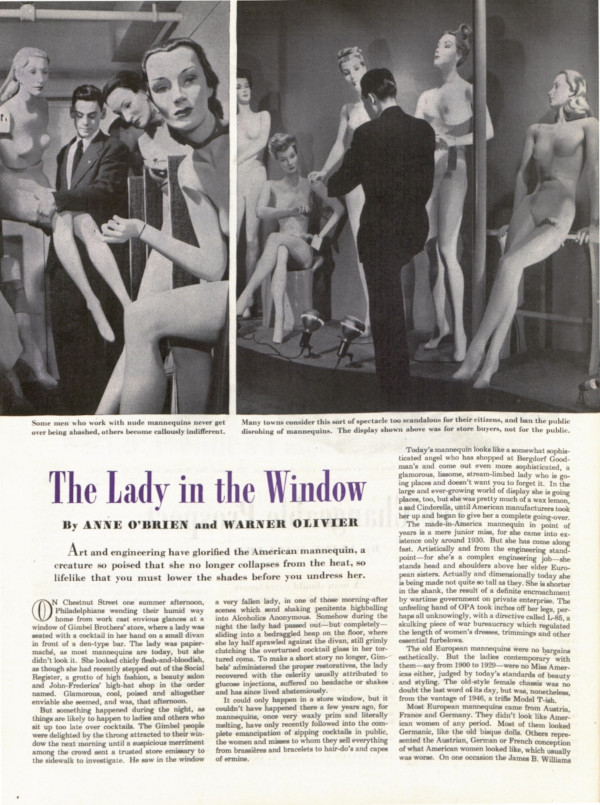

In 1946, when Anne O’Brien and Warner Olivier wrote an article about modern mannequins for The Saturday Evening Post, most of them were made of papier-mâché. But the focus of the article was not the materials, but the mood, for the mannequins in U.S. store windows were a uniquely American creation: “more sophisticated, a glamorous, lissome, stream-limbed lady who is going places and doesn’t want you to forget it.”

The authors found the earlier, European versions of mannequins wanting:

Most European mannequins came from Austria, France and Germany. They didn’t look like American women of any period. Most of them looked Germanic, like the old bisque dolls. Others represented the Austrian, German or French conception of what American women looked like, which usually was worse.

During the Depression, pricey wax mannequins were replaced by two-dimensional cutouts called Woodikins. A bit later, Cora Scovil created stuffed cloth mannequins with embroidered faces, called Patch Poster models. The mannequin took another leap forward when designer Sidney Ring created a lifelike, sophisticated model for Saks Fifth Avenue; he named her Cynthia. Gaba’s fondness for his creation was something else.

Cynthia lived with Gaba in an air-conditioned apartment where she couldn’t melt, presided at his dinner table, wore fresh orchids every day and visited night spots, escorted by her creator. She even wrote a magazine piece describing herself as a homebody.

Cynthia was the launching pad for a decade of improvements that made mannequins lighter, more flexible, and much more realistic.

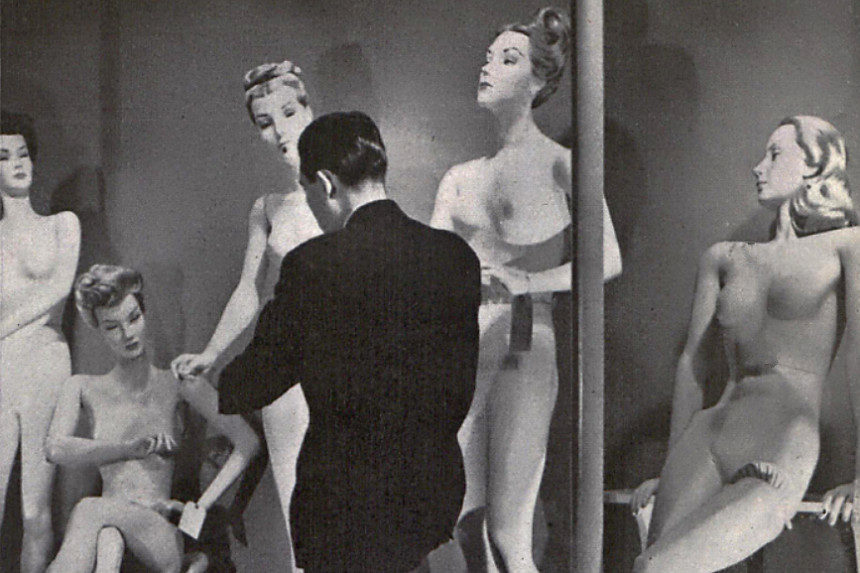

The lifelike mannequins presented their own set of problems. It was considered unseemly to have (largely male) display managers man-handling nude women in store windows, even if the women were made of plaster. Many cities passed ordinances to deal with such improprieties:

In no inconsiderable number it is against the law to disrobe or rerobe a mannequin in a window without putting the shades down. Even in New York a merchant was haled into court for assembling mannequins in his window without putting slips or girdles on them. In Boston it was necessary until comparatively recent years to play down the lipstick and fingernail polish on mannequins.

Beauty didn’t come cheap; the best mannequins sold for $175 ($2,500 today). The price isn’t surprising given that each mannequin was painstakingly sculpted by a craftsman. Each one took 45 to 65 hours to make, a process that took four to six weeks because of the repeated papier-mache application, drying, and sanding that was involved.

And it was a craft, subject to the tastes and talents of the workers who made the mannequins. Unfortunately, they didn’t always get it right:

[Mannequin manufacturer] Lillian Greneker found some of her mannequins coming out of the shop with ankles which wouldn’t pass muster. She called in her underpinning man, Dominick, and told him to take a look at some shapely human ankles somewhere and point up those he was working on.

The next day he called her in to look at the improvements he had made. ” You’re right,” he assured her. ” I look at the ladies’ ankles in the subway and I see what you mean.” Mrs. Greneker took a look. “Well, Dominick,” she told him, “you’d better look a little higher, because the knees aren’t so good either.”

Featured image: photo by David Robbins

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I love the information. Years ago, I insisted on purchasing a dress from a mannequin in the window because I loved it and it was my size. None were available in the store. I loved it and was very happy that the store removed the dress for me. Very chic.

Mannequins are something I don’t have prior knowledge on, and it’s a very fascinating topic. I had ‘access denied’ for ‘The ‘Lady in the Window’ 1946 link, unfortunately, but appreciate the above portion by the Post Editors. I’m not sure what the disclaimer was addressing specifically, but understand why you have to ‘cover yourselves’ in these times.

Having a legal oriented mind, I can appreciate such dilemmas. A disclaimer is the only way to go, so features of the past can be presented in their true form from the time, without being censored otherwise. That would be wrong.

First, to the Post: I see no reason why you need to apologize in case a snow flake is offended by a past article. I say put on your big girl/boy pants and get over it. That’s just the way it was & was acceptable socially.

Next, in more of a question to whoever may have the correct knowledge. I read an article somewhere several years back that there were corpses of young good looking people who prematurely passed with no family that were used to make mannequins. I remember reading their blood was drained and in effect embalmed then situated in a position before a waxy plastic was sprayed over them to preserve their body and subsequently the completed mannequin.Does anyone out there know anything about this and can validate this? It really wreaks of a topic of a horror movie from back in the day.