It may take years before we realize all the ways the COVID-19 pandemic has affected us.

It changed where and how we worked and how we dressed, socialized, and even voted.

It also changed what and how we ate.

According to a survey by the International Food Information Council, Roughly 85 percent of Americans changed their food habits at the beginning of the pandemic. Purchases of flour, sugar, canned soup, and alcohol sales spiked. A survey by marketing agency Influence Central found that 24 percent of respondents reported eating fewer vegetables, 21 percent less fruit, and 19 percent less protein; they also reported that nearly half the subjects ate more sweets.

This isn’t surprising considering that even healthy adults eat more of these foods when under stress. Boredom from social isolation can also contribute to bad eating habits.

Survivors of the Black Death had similar reactions. During the 14th century, as the epidemic of Bubonic plague was killing about half of Europe, wealthy and privileged Europeans escaped to the country, where they lived on rich, indulgent diets, the assumption being that comfort foods were healthy foods.

When COVID hit, not everyone chose the medieval route. Many took the opportunity to eat better. The Influence Central survey (where some admitted to eating fewer fruits and veggies) found 43 percent ate more fruit, 42 percent increased their vegetable intake, and 30 percent ate more protein.

And many weren’t just eating healthier meals – they were also eating more diverse, creative ones. A poll of 2,000 Americans in lockdown found 60 percent of people — mostly millennials — were using this time to explore new cultures through foreign foods. (The most popular cuisines were, in descending order, Italian, Mexican, American regional, Spanish, French, Middle-Eastern, and Greek.)

“People are moving on to more complex cooking,” Kroger chairman and CEO Rodney McMullen told the New York Times. Even novelty recipes were reported: pancake cereal, cloud bread, and hot chocolate bombs.

The idea of trying new foods during the pandemic also has historical precedents. “In times of war or other upheavals,” says culinary historian Barbara Ketcham Wheaton, “people start eating things they’ve never eaten before. And in most cases will ever want to eat again.” People later avoid foods they associate with hard times in their past.

The author of Savoring the Past: The French Kitchen and Table from 1300 to 1789, Wheaton has studied historical cookbooks reaching as far back as 800 A.D. with the goal of creating a database of 5,000 cookbooks. She has also known culinary history firsthand, studying in Paris at L’Ecole des Trois Gourmandes, the cooking school created by Julia Child, Simone Beck, and Louisette Bertholle. In 1979, she was asked to prepare a medieval dish for a Harvard banquet. She arrived with a roast peacock cooked from a medieval recipe. (The meat was tough and gamey, and there were a lot of leftovers.)

Today, she says, Americans eat better, with more variety and fewer taboos, than any other people in history.

“I think there’s been a great opening-up,” Wheaton says, thanks to a current wealth of books, websites, and television programs on cooking. “Americans are more willing to try new techniques, undertake more preliminary work, and venture into new ingredients.”

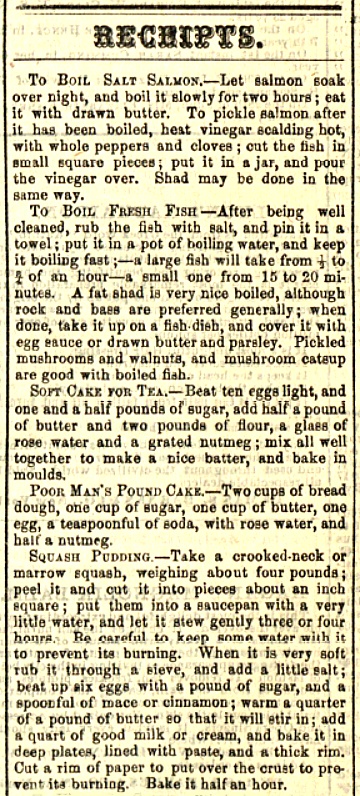

It hasn’t always been so easy to explore new avenues in cuisine. Early American cookbooks, for example, gave minimal details and assumed cooks knew the various techniques needed.

As COVID restrictions were lifted earlier this year, diners eagerly flocked to the restaurants. But the arrival of the new COVID variant has many wondering if they’ll be a return to isolating and a reliance on home cooking. If this happens, cooks may want to expand their culinary repertoire.

Wheaton says there are great rewards for moving toward more challenging dishes. She advises much practice, and taking care not to lose enthusiasm. “The venturing chef should cook something three times, and not anything really fancy until you’ve had a lot of practice.

“Once you’ve mastered a recipe, you know what it sounds like when it’s cooking, how it smells, and when it’s time to rush it to the sink.” It becomes a task your hands automatically perform. Or, as Wheaton says, “It’s there from your wrist on out.” Cooking your new dish becomes a pleasure, she says, almost a ritual dance.

And if mastery fails you, just remember the immortal words of Julia Child: “Maybe the cat has fallen into the stew, or the lettuce has frozen, or the cake has collapsed—eh bien, tant pis! Usually one’s cooking is better than one thinks it is.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

My husband has become the main cook. He likes to experiment and try new things. Having been to Italy right before Covid, we loved the Steven Tucci series and he tried and was very successful at recipes he saw being made on the show. While he cooks (takes over the kitchen), I drink wine and stay out of his way.

The Wheaton book reminds me of my Nana’s recipes. My favorite conundrum was figuring out how much was “butter the size of a walnut” and did I really want to make schmaltz.

I truly enjoyed Ms. Wheaton’s book and I’m glad to have her comments and encouragement as we spend time in the kitchen trying new dishes. More time at home has really inspired me to do more cooking and shopping for things I’ve not tried before, although I have to say the high cost of shipping from an English shop put me back onto shopping locally.