This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The more than 10,000 John Deere workers who went on strike this past week are just the latest in a long and still unfolding series of labor actions around the country. From Hollywood to the health care industry, Kellogg’s and Nabisco plants to sanitation workers in the U.K., these past, present, and proposed collective actions have led some commentators to dub the month “striketober.” Each of these situations features specific factors and circumstances, such as the proposed changes at Nabisco around weekend and overtime shifts that could have resulted in workers making $10,000 less per year than they had been. But the proliferation of all these labor actions at the same moment could be seen as constituting an unofficial general strike, a collective revolt of workers against the substandard conditions and systematic inequities that plague this fraught period in American and world history.

Such general strikes are part of a longstanding and inspiring legacy in American history. But just as longstanding is the use of systematic violence from both corporations and their government allies to respond to these collective labor actions. Two campaigns of anti-labor violence from a century ago illustrate this darker side to our labor histories, and remind us of the stakes of supporting and protecting our contemporary workers as they advocate for their rights and for a more equitable and just society for us all.

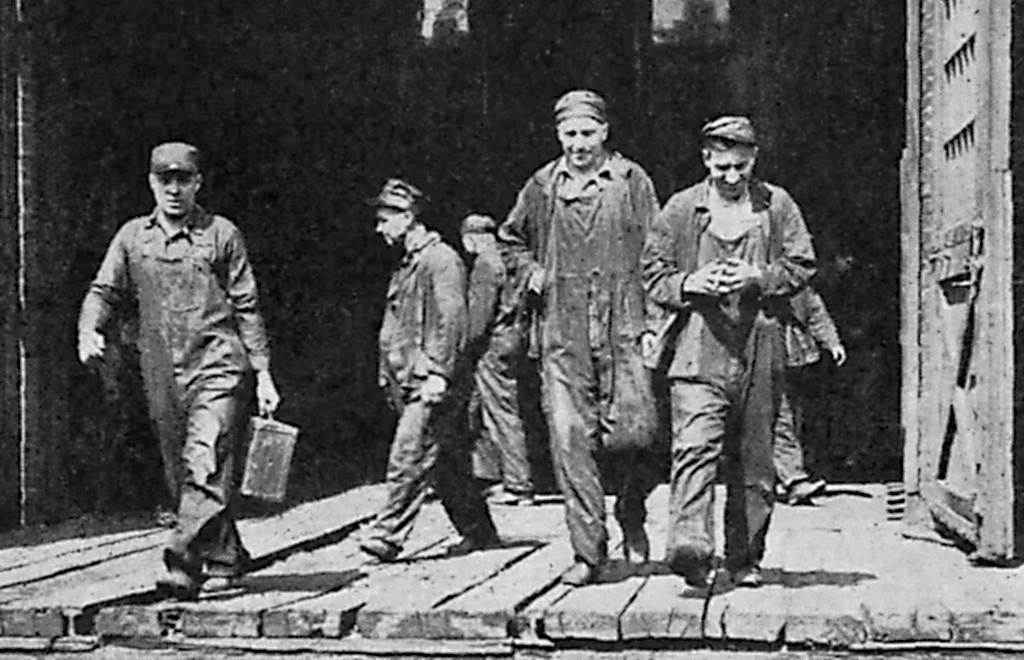

The first of those events has become better remembered in recent years, but under the misleading name the West Virginia Mine Wars. What unfolded in West Virginia between 1912 and 1921 wasn’t a war, but a series of labor actions that were met time and again by violence from both corporate hired guns and their government allies. Beginning in 1912, the United Mine Workers (UMW), a labor union within the American Federation of Labor (AFL), sought to organize miners to protest and change such issues as the lack of health and safety regulations (and the frequent disasters and consistent fatalities that resulted), the long hours and low wages, and the company towns in which miners were forced to live.

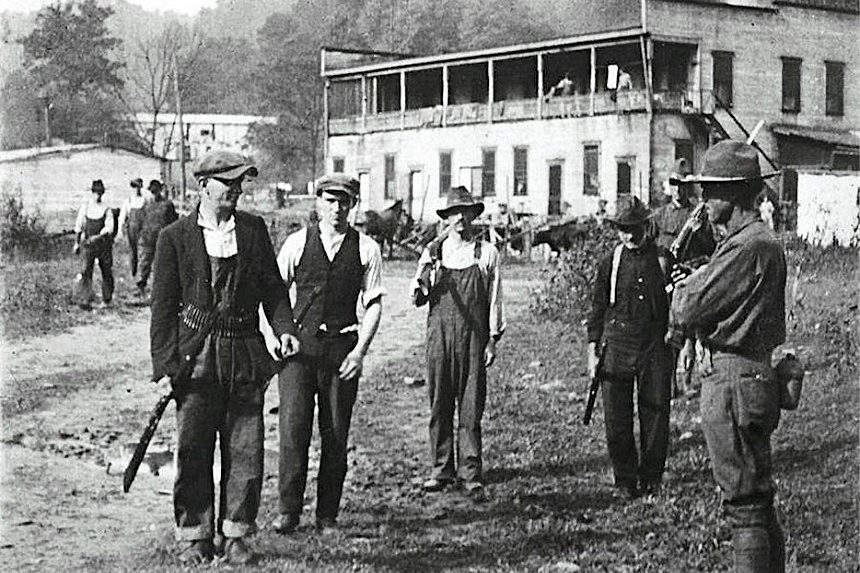

Those attempts at unionization were consistently opposed by repressive and violent responses from the mining corporations and their militarized forces and allies. The most brutal such violence took place in August 1921, when thousands of miners marched 60 miles from Marmet to Mingo County in an attempt to free striking miners imprisoned by Governor Ephraim Morgan (who had declared martial law in the county). Law enforcement and corporate forces under the command of the brutal anti-labor Sheriff Don Chafin ambushed the marchers at Blair Mountain, and the resulting conflict became so heated that President Warren Harding called in 2500 U.S. Army troops to aid in suppressing the miners. The so-called Battle of Blair Mountain was in truth a massacre, one that even included aerial bombardment of the miners by planes under Chafin’s command.

While those labor actions and violent responses were localized to West Virginia and the mining industry, the following summer saw a far more general strike that was met with similar corporate and official brutality. In mid-1922, the Railroad Labor Board (a new government agency that had been created by the Transportation Act of 1920) approved a 12 percent wage cut for repair and maintenance workers, the latest in a series of cuts and other regressive policies put forward by the Board that directly affected railway workers. In response, seven unions representing those workers voted to go on strike, and on July 1, 1922, a general strike was launched, with nearly 400,000 railway workers around the country marching off the job.

Ben W. Hooper, the former Tennessee governor who had been appointed by President Harding to head the Railroad Labor Board, acted swiftly to attack the strikers, passing an “outlaw resolution” on July 3 which declared that the workers had forfeited all bargaining rights and could be replaced by scabs. Spurred on by this measure and the clear support of the federal government, railroad company guards and law enforcement forces began overtly targeting strikers, with shootings of workers reported in Cleveland, Buffalo, Clinton (IL), Port Morris (NJ), Needles (CA), and Wilmington (NC) between July 8 and July 16 alone. Harding and his anti-labor Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty not only sided with this official violence, but also convinced federal judge James H. Wilkerson to issue a sweeping anti-labor injunction on September 1; this extreme “Daugherty Injunction” declared striking, picketing, and many other labor actions illegal, effectively ending the strike and making future such actions far more difficult and dangerous.

Such anti-labor repression and violence was also part of an overarching, systematic plan in the period to destroy unions and the labor movement. Initially formulated by a group of Midwestern corporations at a 1921 meeting in Chicago, then adopted more generally by the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) in 1922, this tellingly named “American Plan” called for overt violence against union organizers and striking workers, much of it perpetrated by armed “patrols” that the NAM would pay to import into unionized cities and target union gatherings and labor actions. In one particularly horrific example, in November 1927, members of an armed patrol and state militia allies fired into a group of striking coal miners in Serene, Colorado, killing six and injuring many more in an event that came to be known as the Columbine Mine massacre.

Over the course of the decade, this combination of specific violence and systematic repression, first modeled in West Virginia and around the country in the summers of 1921 and 1922 and then launched more formally as the American Plan, succeeded in reducing the number of workers involved in labor actions from more than 4 million in 1919 to less than 300,000 in 1929.

If we are entering a new era of labor activism, American history offers lessons not only for such collective action, but for what happens when violent responses to it from both industry and law enforcement forces become normalized. May the 2020s be an era in which we instead support and protect the workers, organizations, and allies fighting for rights and justice.

Featured image: Miners surrendering to federal troops after the Battle of Blair Mountain (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

An excellent article. One thing no generation seems to have a dearth of are sociopaths. There are exceptions to the following, but I tend to suspect that someone who rises to the top ( whatever that may be ) in a given field is more than a little bit of a sociopath.

F’rinstance: he may not be a sociopath, but the way Jeff Bezos treats employees in his dreadful sweatshops makes me ponder the idea that he could be. ( Am I the only one who senses that there is an evil, Orwellian joke in the term, “fulfillment centers?” )

The mood of the country is overripe for a leader who can harness the proper fury of most of bottom 90% against the New Oligarchs. Will the Left be able to put aside its obsession with Wokeness, the Right, its obsession with Trump and the notion that last year’s election was stolen, so that a coalition of the economically outraged can be formed?

I’m afraid I doubt it. There’s too much mutual, irrational hatred in the body politic.

It certainly appears that with each new age of awareness (Renaissance, Age of Discovery, Reformation, Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, Globalization, the Digital Revolution, the Information Age) there is also conflict.

We’re now in the infancy of the Information Age. People are still beginning to learn how to use the new tools, which are undergoing constant change. That in itself causes friction which can definitely lead to conflict. Some are testing the waters to see just how much they can get away with, very much like growing children.

One seeming constant among all these ages is the existence of those who wish to rule others. If not with birthright then with might. Greece tested democracy and it is evolving still. Too many outside influences will make it unrecognizable while still calling it by it’s name.

Maybe we can avoid as much violence with our upcoming conflict this time.

BTW:

fraught – freight, filled with, laden, etc.

Those who don’t study history are doomed to repeat it.

Too bad government schools don’t teach as much history as they did once.

The quickest way to truly destroy a society is to ruin their language and education.

The result is a people that can’t communicate effectively and don’t know of what they speak.

Thoughtful, rational discourse will be limited to the elites.