This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

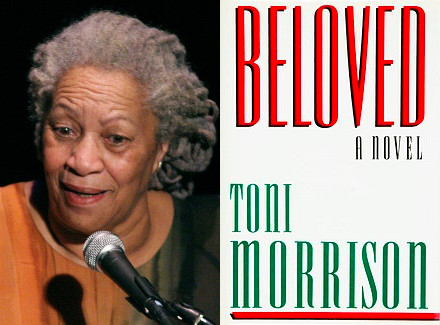

On Tuesday, Virginia voters head to the polls to elect the state’s next Governor, in a tightly contested race between Democratic former Governor Terry McAuliffe and Republican businessman Glenn Youngkin. In this final pre-election week, the Youngkin campaign released its closing TV advertisement, featuring Virginia mother Laura Murphy who in 2013 was blocked by Governor McAuliffe in her quest to get a book banned from Fairfax County classrooms. That book was Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning historical novel Beloved (1987), which Murphy’s son (now a lawyer for the National Republican Congressional Committee) had read in his senior year AP English class and which, Laura Murphy claims in the ad, gave him “night terrors.”

Like any campaign commercial, this one is certainly caught up in all the specifics of this candidate, race, place, and moment. But it’s also part of our larger political and cultural debates, particularly those surrounding education and race in America. Both Murphy’s objection to Morrison’s novel and some core details of Beloved itself capture succinctly a frustrating, fundamental 2021 divide: between critiques of “Critical Race Theory” and its supposed effects on white students on the one hand, and two of the vital goals of education on the other. Those two goals are 1. to challenge our established prior perspectives, uncomfortable as that process always will be; and 2. to understand and appreciate our shared connections, what links all those who are part of our communities and nation.

As state laws seeking to ban Critical Race Theory (CRT) and other forms of anti-racist education have proliferated in recent months, one of the main arguments advanced by supporters of those proposals has been that such educational frameworks can negatively affect white students. Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice expressed that perspective clearly in a recent appearance on ABC’s morning show The View, arguing in response to a question about CRT that “I don’t want to make white kids feel bad for being white. So, somehow this is a conversation that has gone in the wrong direction.”

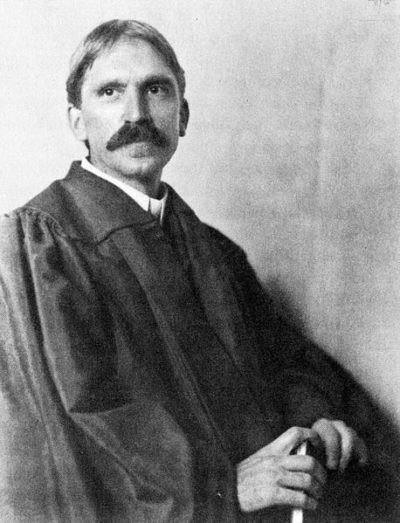

Every good teacher is centrally concerned with their students, and none of us wants any of those students feeling bad. But arguments such as Rice’s conflate genuinely negative emotions (like “guilt”) with a far more productive and even necessary feeling: discomfort. To quote John Dewey, one of the most important educational thinkers in American history: “The path of least resistance and least trouble is a mental rut already made. It requires troublesome work to undertake the alteration of old beliefs.” One essential goal of education is to challenge our established prior perspectives, to push us to new ideas and understandings; and as Dewey knew, such change and growth is necessarily and importantly uncomfortable.

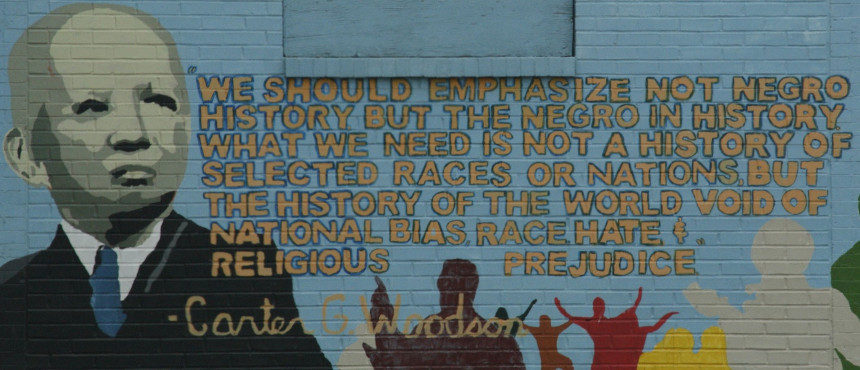

Moreover, education isn’t solely about our own perspectives nor our own feelings. It’s just as importantly about learning to understand, feel for, and connect with all those who are part of our shared communities. As Carter Woodson, the educational pioneer who founded “Negro History Week” (the predecessor to Black History Month) in February 1926, described that initiative’s goals, “We should emphasize not Negro history, but the Negro in history.” Of course adding Black history to American curricula was and remains a vital step for Black students, to see themselves better represented in their own education. But it is even more crucial for white students, as recognizing that Black history is American history encapsulates a second essential educational goal: understanding the connections that we all share.

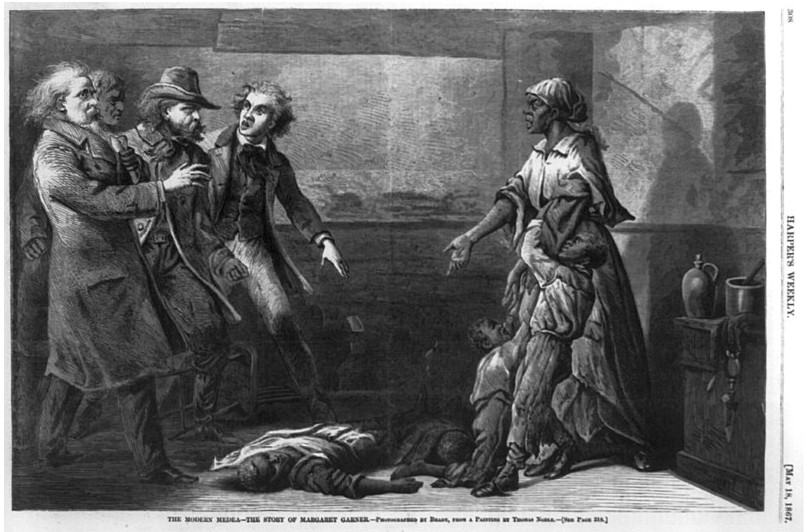

Toni Morrison’s masterpiece Beloved is an important text to share with students for many reasons, but chief among them are its contributions to both of these essential educational goals. Beloved is at its heart a ghost story, and like all such spooky tales creates a great deal of discomfort. The histories that haunt the novel’s characters and readers alike are indeed terrifying, all the more so because they were inspired by a real figure and a horrific historical event: Margaret Garner, an antebellum American woman who murdered her own two-year-old daughter and wounded her other three children rather than see them returned to a state of enslavement. Both reading Morrison’s historical fiction and learning about Garner force us to confront some of the hardest and most painful layers to slavery and American history, an uncomfortable but important process.

The brief concluding section of Beloved explicitly addresses the understandable desire to forget such painful histories. “This is not a story to pass on,” Morrison’s narrator repeats multiple times in those culminating pages, seemingly endorsing that its characters and readers should leave the story’s haunting histories behind. But “pass on” can also mean “miss out on” (as in “I’ll pass”), and the novel’s final sentence, the single word “Beloved” (the name of the book’s ghostly murdered child), ensures that readers cannot miss nor forget its focal histories of enslavement and freedom, racism and resistance. Throughout the novel, Morrison has developed the concept of rememory (a word of her own invention), an idea that emphasizes not just the past itself, but the process of bringing it back into our perspectives and communities. The book models that process, helping all its readers better remember the kinds of American stories that for far too long we have passed on.

The chief villain of Beloved is a brutal slaveowner tellingly named Schoolteacher. That man and the system he represents are violent not only in their direct actions, but also in the erasures of Black agency, identity, and community. Classrooms and education that exclude histories of race and racism, that ban Beloved and miss Margaret Garner, would replicate and extend those erasures — erasures that are deeply intertwined with, indeed are in many ways prerequisites for, systems of white supremacist discrimination and violence.

Whatever the outcome of individual elections or political debates, we should remember the importance of being open to challenges to our beliefs and seeing the connections we all share, both in our classes and everywhere else.

Featured image: Illustration depicting Margaret Garner from Harper’s Weekly (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

That which makes me uncomfortable makes me stronger.