The story takes place on a deserted island somewhere in the Pacific. A plane has just gone down. The only survivors are some British schoolboys. Nothing but beach, shells, and water for miles. And no grown-ups.

On the very first day, the boys institute a democracy of sorts. One boy — Ralph — is elected to be the group’s leader. His game plan is simple: 1) Have fun. 2) Survive. 3) Make smoke signals for passing ships.

Number one is a success. The others? Not so much. Most of the boys are more interested in feasting and frolicking than in tending the fire. Jack, a redhead, develops a passion for hunting pigs, and as time progresses he and his friends grow increasingly reckless. When a ship does finally pass in the distance, they’ve abandoned their post at the fire.

“You’re breaking the rules!” Ralph accuses angrily.

Jack shrugs. “Who cares?”

“The rules are the only thing we’ve got!”

When night falls, the boys are gripped by terror, fearful of the beast they believe is lurking on the island. In reality, the only beast is inside them. Before long, they’ve begun painting their faces. Casting off their clothes. And they develop overpowering urges — to pinch, to kick, to bite.

Of all the boys, only one manages to keep a cool head. Piggy, as the others call him because he’s pudgier than the rest, is the voice of reason, to whom nobody listens. “What are we?” he wonders mournfully. “Humans? Or animals? Or savages?”

Weeks pass. Then, one day, a British naval officer comes ashore. The island is now a smoldering wasteland. Three of the children, including Piggy, are dead. “I should have thought,” the officer reproaches them, “that a pack of British boys would have been able to put up a better show than that.” Ralph, the leader of the once proper and well-behaved band of boys, bursts into tears.

“Ralph wept for the end of innocence,” we read, and for “the darkness of man’s heart …”

This story never happened. An English schoolmaster made it up in 1951. “Wouldn’t it be a good idea,” William Golding asked his wife one day, “to write a story about some boys on an island, showing how they would really behave?”

Golding’s book Lord of the Flies would ultimately sell tens of millions of copies, be translated into more than 30 languages, and be hailed as one of the classics of the 20th century.

In hindsight, the secret to the book’s success is clear. Golding had a masterful ability to portray the darkest depths of mankind. “Even if we start with a clean slate,” he wrote in his first letter to his publisher, “our nature compels us to make a muck of it.” Or as he later put it, “Man produces evil as a bee produces honey.”

The book was an instant hit. So much so, argued the influential critic Lionel Trilling, that the novel “marked a mutation in culture.” Eventually, Golding even won a Nobel Prize. His work “illuminate[s] the human condition in the world of today,” wrote the Swedish Nobel committee, “with the perspicuity of realistic narrative art and the diversity and universality of myth.” These days, Lord of the Flies is read as far more than “just” a novel. Sure, it’s a made-up story shelved with all the other fiction, but Golding’s take on human nature has also made it the veritable textbook on veneer theory — the notion that civilization is nothing more than a thin veneer that will crack at the merest provocation. Before Golding, nobody had ever attempted such raw realism in a book about children. Instead of sentimental tales of houses on prairies or lonely little princes, here — ostensibly — was a harsh look at what kids are really like.

I first read Lord of the Flies as a teenager. I remember feeling disillusioned afterward, as I turned it over and over in my mind. But not for a second did I think to doubt Golding’s view of human nature.

That didn’t happen until I picked up the book again years later. When I began delving into the author’s life, I learned what an unhappy individual he’d been. An alcoholic. Prone to depression. A man who beat his kids. “I have always understood the Nazis,” Golding confessed, “because I am of that sort by nature.”

And so I began to wonder: Had anyone ever studied what real children would do if they found themselves alone on a deserted island? I wrote an article on the subject, in which I compared Lord of the Flies to modern scientific insights and concluded that, in all probability, kids would act very differently. I cited biologist Frans de Waal, who said, “There is no shred of evidence that this is what children left to their own devices will do.”

Readers of that piece responded skeptically. All my examples concerned kids at home, at school, or at summer camp. They didn’t answer the fundamental question: What happens when kids are left on a deserted island all alone?

Thus began my quest for a real-life Lord of the Flies.

I started with a basic internet search — “Kids shipwrecked” “Real-life Lord of the Flies” “Children on an island” — and I came across an obscure blog that told an arresting story: “One day, in 1977, six boys set out from Tonga on a fishing trip. … Caught in a huge storm, the boys were shipwrecked on a deserted island. What do they do, this little tribe? They made a pact never to quarrel.”

I discovered that the story came from a book by a well-known anarchist, Colin Ward, titled The Child in the Country (1988). Ward, in turn, cited a report by an Italian politician, Susanna Agnelli, compiled for some international committee or other.

Okay, I thought, maybe I can track down this Susanna Agnelli and ask where she got the story. But no such luck: She’d passed away in 2009. If this had really happened, I reasoned, there must be an article about it from 1977. Not only that, the boys could still be alive. But search as I might in archive upon archive, I couldn’t find a thing.

Sometimes all it takes is a stroke of luck. Sifting through a newspaper archive one day, I typed a year incorrectly and ended up deep in the 1960s. And there it was. The reference to 1977 in Agnelli’s report turns out to have been a typo.

In the October 6, 1966, edition of Australian newspaper The Age, a headline jumped out at me: “Sunday Showing for Tongan Castaways.” The story concerned six boys who had been found three weeks earlier on a rocky islet south of Tonga, an island group in the Pacific Ocean. The boys had been rescued by an Australian sea captain after being marooned on the island of ‘Ata for more than a year.

According to the article, the captain had even gotten a television station to film a reenactment of the boys’ adventure.

“Their survival story already is regarded as one of the great classic stories of the sea,” the piece concluded.

I was bursting with questions. Were the boys still alive? And could I find the television footage? Most importantly, though, I had a lead: the captain’s name was Peter Warner.

As I did a search for the captain’s name, I had another stroke of luck. In a recent issue of the Daily Mercury, a tiny local paper from Mackay, Australia, I came across the headline: “MATES SHARE 50-YEAR BOND.” Printed alongside was a small photograph of two men, smiling, one with his arm slung around the other. The article began: “Deep in a banana plantation at Tullera, near Lismore, sits an unlikely pair of mates. … These men have laughing eyes and a sparkling energy that belies their age. The elder is 83 years old, the son of a wealthy industrialist. The younger, 67, was, literally, a child of nature.”

Their names? Peter Warner and Mano Totau. And where had they met?

On a deserted island.

We set out one September morning. My wife Maartje and I had rented a car in Brisbane, on Australia’s east coast, and some three hours later we arrived at our destination, a spot in the middle of nowhere that stumped Google Maps. Yet there he was, sitting out in front of a low-slung house off this dirt road: the man who rescued six lost boys 50 years ago. Captain Peter Warner.

Before I tell his story, there are a few things you should know about Peter, because his life alone is worth a movie. He was born the youngest son of Arthur Warner, once one of the richest and most powerful men in Australia. Back in the 1930s, Arthur ruled over a vast empire called Electronic Industries, which dominated the country’s radio market at the time.

Peter had been groomed to follow in his father’s footsteps. Instead, at the age of 17, he ran away. He went to sea in search of adventure. “I’d prefer to fight nature rather than human beings,” he later explained.

Peter spent the next few years sailing the seven seas, from Hong Kong to Stockholm, from Shanghai to St. Petersburg. When he finally returned five years later, the prodigal son proudly presented his father with a Swedish captain’s certificate. Unimpressed, Warner Sr. demanded his son learn a useful profession.

“What’s easiest?” Peter asked.

“Accountancy,” Arthur lied.

It took another five years of night school for Peter to earn his degree. He went to work for his father’s company, yet the sea still beckoned, and whenever he could get away, Peter went to Tasmania, where he kept his own fishing fleet. It was this fishing on the side that brought him to Tonga in the winter of 1966. He had arranged an audience with the king to ask permission to trap lobster in Tongan waters. Unfortunately, His Majesty Tāufa‘āhau Tupou IV refused.

Disappointed, Peter headed back to Tasmania, but on the way he took a little detour, outside royal waters, to cast his nets. And that’s when he saw it: a minuscule island in the azure sea.

The island of ‘Ata.

Peter knew that no ships had anchored there in ages. The island had been inhabited once, up until one dark day in 1863, when a slave ship appeared on the horizon and sailed off with the natives. Since then, “‘Ata had been deserted — cursed and forgotten.”

But Peter noticed something odd. Peering through his binoculars, he saw burned patches on the green cliffs. “In the tropics it’s unusual for fires to start spontaneously,” he told us a half-century later. “So I decided to investigate.” As his boat approached the western tip of the island, Peter heard a shout from the crow’s nest.

“Someone’s calling!” yelled one of his men.

“Nonsense,” Peter shouted back. “It’s just squawking seabirds.” But then, through his binoculars, he saw a boy. Naked. Hair down to his shoulders. This wild creature leaped from the cliffside and plunged into the water. Suddenly more boys followed, screaming at the top of their lungs.

piece of driftwood, half a coconut shell, and six steel wires salvaged from their boat. (John Carnemolla)

Peter ordered his crew to load their guns, mindful of the Polynesian custom of dumping dangerous criminals on remote islands. It didn’t take long for the first boy to reach the boat. “My name is Stephen,” he cried in perfect English. “There are six of us and we reckon we’ve been here fifteen months.”

Peter was more than a little skeptical. The boys, once aboard, claimed they were students at a boarding school in Nuku‘alofa, the Tongan capital. Sick of school meals, they had decided to take a fishing boat out one day, only to get caught in a storm.

Likely story, Peter thought. Using his two-way radio, he called in to Nuku‘alofa. “I’ve got six kids here,” he told the operator. “If I give you their names, can you telephone the school to find out if they’re pupils there?”

“Stand by,” came the response.

Twenty minutes ticked by. (As Peter tells this part of the story, he gets a little misty-eyed.)

Finally, “A very tearful operator came on the radio and said, ‘You found them! These boys have been given up for dead. Funerals have been held. If it’s them, this is a miracle!’”

I asked Peter if he’d ever heard of the book Lord of the Flies. “Yes, I’ve read it,” he laughed. “But that’s a completely different story!”

In the months that followed I tried to reconstruct as precisely as possible what had happened on that tiny island of ‘Ata. Peter’s memory turned out to be excellent. Even at the age of 90, everything he recounted was consistent with the other sources. My foremost other source lived a few hours’ drive from Peter.

Mano Totau, 15 years old at the time and now pushing 70, counted the captain among his closest friends. A couple days after our visit with Peter, Mano was waiting to welcome me and my wife in his garage in Deception Bay, just north of Brisbane.

The real Lord of the Flies, Mano told us, began in June 1965.

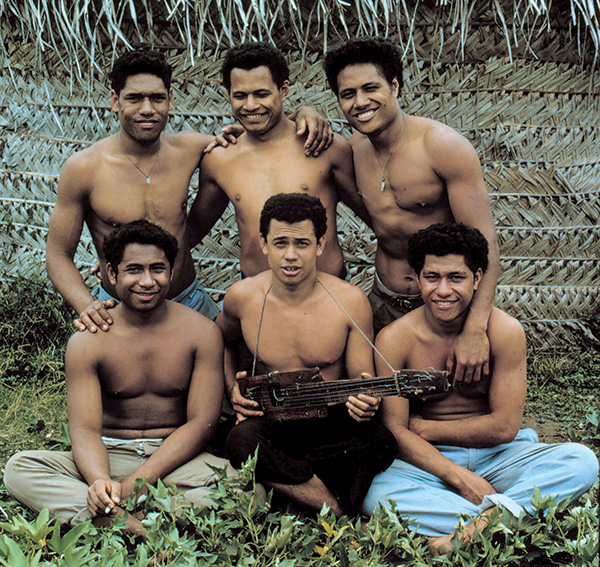

The protagonists were six boys, all pupils at St. Andrew’s, a strict Catholic boarding school in Nuku‘alofa. The oldest was 16, the youngest 13, and they had one main thing in common: They were bored witless. The teenagers longed for adventure instead of assignments, for life at sea instead of school.

So they came up with a plan to escape — to Fiji, some 500 miles away, or even all the way to New Zealand. “Lots of other kids at school knew about it,” Mano recalled, “but they all thought it was a joke.”

There was only one obstacle. None of them owned a boat, so they decided to “borrow” one from a fisherman they all disliked.

The boys took little time to prepare for the voyage. Two sacks of bananas, a few coconuts and a small gas burner were all the supplies they packed. It didn’t occur to any of them to bring a map, let alone a compass. And none of them was an experienced sailor. Only the youngest, David, knew how to steer a boat (which, according to him, “was why they wanted me to come along”).

The journey began without a hitch. No one noticed the small craft leaving the harbor that evening. Skies were fair; only a mild breeze ruffled the calm sea.

But that night the boys made a grave error. They fell asleep. A few hours later they awoke to water crashing down over their heads. It was dark. All they could see were foaming waves cresting around them. They hoisted the sail, which the wind promptly tore to shreds. Next to break was the rudder.

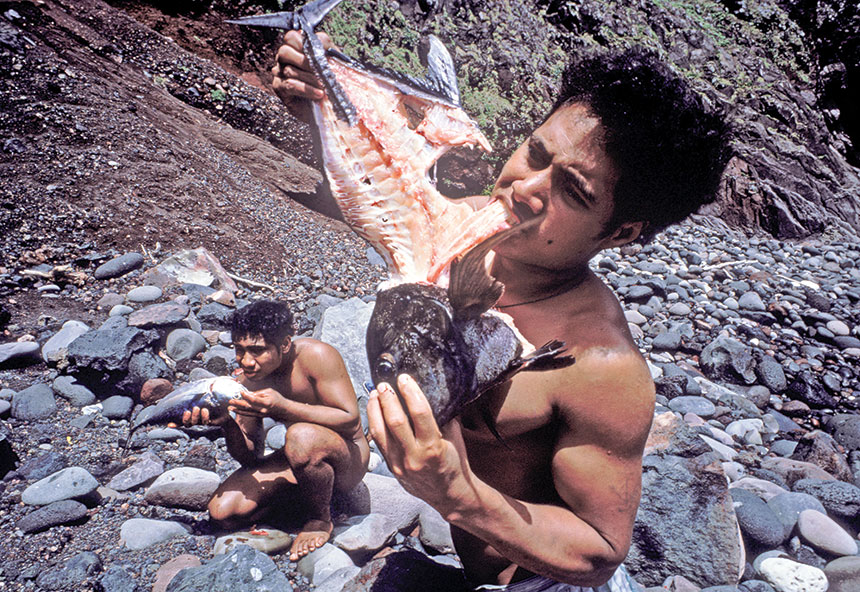

“We drifted for eight days,” Mano told me. “Without food. Without water.” The boys tried catching fish. They managed to collect some rainwater in hollowed-out coconut shells and shared it equally between them, each taking a sip in the morning and another in the evening. Sione tried boiling seawater on the gas burner, but it tipped over and burned a large part of his leg.

Then, on the eighth day, they spied a miracle on the horizon. Land. A small island to be precise. Not a tropical paradise with waving palm trees and sandy beaches, but a hulking mass of rock, jutting up more than a thousand feet out of the ocean.

These days, ‘Ata is considered uninhabitable. A rugged Spanish adventurer found this out a few years ago. He thought it might be a good spot for the shipwreck expeditions he organizes for rich folk with unusual needs. He went to check it out, but just nine days in the poor guy had to call it quits. When a journalist asked if his company would be expanding to the rocky outcrop, he answered in no uncertain terms.

“Never. The island is far too tough.”

The teenagers had a rather different experience. “By the time we arrived,” Captain Warner wrote in his memoirs, “the boys had set up a small commune with food garden, hollowed-out tree trunks to store rainwater, a gymnasium with curious weights, a badminton court, chicken pens, and a permanent fire, all from handiwork, an old knife blade, and much determination.”

It was Stephen — later an engineer — who, after countless failed attempts, managed to produce a spark using two sticks. While the boys in the make-believe Lord of the Flies come to blows over the fire, those in the real-life Lord of the Flies tended their flame so it never went out, for more than a year.

The kids agreed to work in teams of two, drawing up a strict roster for garden, kitchen, and guard duty. Sometimes they quarreled, but whenever that happened they solved it by imposing a time-out. The squabblers would go to opposite ends of the island to cool their tempers, and, “After four hours or so,” Mano later remembered, “we’d bring them back together. Then we’d say ‘Okay, now apologize.’ That’s how we stayed friends.”

Their days began and ended with song and prayer. Kolo fashioned a makeshift guitar from a piece of driftwood, half a coconut shell, and six steel wires salvaged from their wrecked boat — an instrument Peter has kept all these years — and played it to help lift their spirits.

And their spirits needed lifting. All summer long it hardly rained, driving the boys frantic with thirst. They tried constructing a raft in order to leave the island, but it fell apart in the crashing surf. Then there was the storm that swept across the island and dropped a tree on their hut.

Worst of all, Stephen slipped one day, fell off a cliff, and broke his leg. The other boys picked their way down after him and then helped him back up to the top. They set his leg using sticks and leaves. “Don’t worry,” Sione joked. “We’ll do your work, while you lie there like King Tāufa‘āhau Tupou himself!”

The boys were finally rescued on Sunday, September 11, 1966. Physically, they were in peak condition. But this wasn’t the end of the boys’ little adventure, because when they arrived back in Nuku‘alofa, they found the police waiting to meet them. You might expect the officers to have been thrilled at the return of the town’s six lost sons. But no. They boarded Peter’s boat, arrested the boys, and threw them in jail. Mr. Taniela Uhila, whose sailing boat the boys had “borrowed” 15 months earlier, was furious, and he’d decided to press charges. Fortunately for the boys, Peter came up with a plan. It occurred to him that the story of their shipwreck was perfect Hollywood material. Six kids marooned on an island … it was a tale people would be talking about for years. And being his father’s corporate accountant, Peter managed the company’s movie rights and knew people in television.

The captain knew exactly what to do. First, from Tonga, he called up the manager of Channel 7 in Sydney. “You can have the Australian rights,” he told them. “Give me the world rights. Then we’ll spring these kids out of prison and take them back to the island.” Next, Peter went around to see Mr. Uhila and paid him £150 for his old boat, getting the boys released on the condition that they would cooperate with the movie.

A few days later, a team from Channel 7 arrived in the ancient DC-3 that flew a once-weekly service to Tonga. Describing the scene to Maartje and me, Peter chuckles. “Out of that aircraft stepped three of those TV types in their city suits and pointy shoes.” By the time the group arrived on ‘Ata with the six boys in tow, the gang from Channel 7 was green around the gills. Worse, they didn’t know how to swim. “Don’t worry,” Peter assured them. “These boys will save you.”

The captain rowed the trembling men out to the breakers. “This is where you get out.”

Even 50 years later, the memory brings tears to Peter’s eyes — this time from laughter. “So I tossed them out, and these Australian television people were sinking down, the Tongans diving down, picking them up, taking them through the surf, bashing them up against the rocks.”

Next, the group had to scale the cliff, which took the rest of the day. When they finally arrived at the top, the TV crew collapsed, exhausted. Not surprisingly, the documentary about ‘Ata was no success. Not only were the shots lousy, but most of the 16mm film went missing, leaving a grand total of only 30 minutes. “Actually,” Peter amends, “20 minutes, plus commercials.”

Naturally, as soon as I heard about the Channel 7 documentary I wanted to see it. Peter put me in touch with an independent filmmaker named Steve Bowman who had visited the “boys” in 2006. Steve was frustrated that their story had never got the attention it deserved. His own documentary had never aired because his distributor went bankrupt, but he still had his raw interviews. He kindly offered to share them with me and also to put me in touch with Sione, the oldest of the bunch. Then he announced that he had the sole remaining copy of that original 16mm documentary.

“May I see it?” I asked Steve.

“Of course,” he answered.

And that’s how — months after stumbling across a story on an obscure blog about six shipwrecked kids — I was suddenly watching the original 1966 footage on my laptop. “I am Sione Fataua,” it began. “Five classmates from St. Andrew’s High School and I washed ashore on this island in June 1965.”

The mood when the boys returned to their families in Tonga was jubilant. Almost the entire island of Ha‘afeva — population 900 — had turned out to welcome them home. “No sooner did one party end than preparations for another began,” narrated the 1966 documentary voiceover.

Peter was proclaimed a national hero. Soon he received a message from King Tāufa‘āhau Tupou IV himself, inviting the captain for another audience. “Thank you for rescuing six of my subjects,” His Royal Highness said. “Now, is there anything I can do for you?”

The captain didn’t have to think long. “Yes! I would like to trap lobster in these waters and start a business here.”

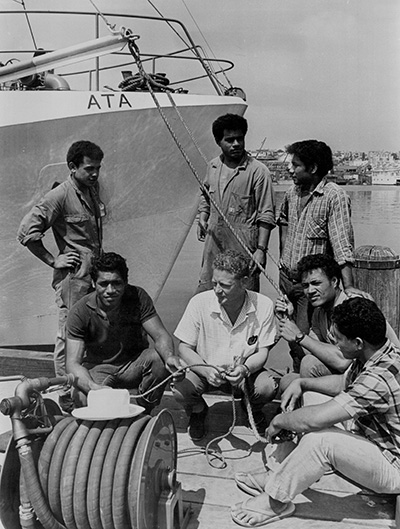

This time the king consented. Peter returned to Sydney, resigned from his father’s company, and commissioned a new ship. Then he had the six boys brought over and granted them the thing that had started it all: an opportunity to see the world beyond Tonga. He hired Sione, Stephen, Kolo, David, Luke, and Mano as the crew of his new fishing boat.

The name of the boat? The Ata.

This is the real-life Lord of the Flies.

Turns out, it’s a heart-warming story — the stuff of bestselling novels, Broadway plays, and blockbuster movies.

It’s also a story that nobody knows. While the boys of ‘Ata have been consigned to obscurity, William Golding’s book is still widely read. Media historians even credit him as being the unwitting originator of one of the most popular entertainment genres on television today: reality TV.

The premise of so-called reality shows, from Big Brother to Temptation Island, is that human beings, when left to their own devices, behave like beasts. “I read and re-read Lord of the Flies,” divulged the creator of the hit series Survivor in an interview. “I read it first when I was about 12, again when I was about 20, and again when I was 30, and since we did the program as well.”

The show that launched this whole genre was MTV’s The Real World. Since it first aired in 1992, every episode opens with a cast member reciting, “This is the true story of seven strangers. … Find out what happens when people stop being polite and start getting real.”

Lying, cheating, provoking — these are what each installment would have us believe it means to “get real.” But take the time to look behind the scenes of programs like these and you’ll see candidates being led on, boozed up, and played off against each other in ways that are nothing less than shocking. It shows just how much manipulation it takes to bring out the worst in people.

You could say: What does it really matter? We all know it’s just entertainment.

But in a recent study, psychologist Bryan Gibson demonstrated that watching Lord of the Flies-type television can make people more aggressive. Furthermore, cynical stories have an even more marked effect on the way we look at the world. In Britain, another study demonstrated that girls who watch more reality TV also more often say that being mean and telling lies are necessary to get ahead in life. As media scientist George Gerbner summed up: “[He] who tells the stories of a culture really governs human behavior.”

It’s time we told a different kind of story.

The real Lord of the Flies is a story of friendship and loyalty, a story that illustrates how much stronger we are if we can lean on each other. Of course, it’s only one story. But if we’re going to make Lord of the Flies required reading for millions of teenagers, then let’s also tell them about the time real kids found themselves stranded on a deserted island. “I used their survival story in our social studies classes,” one of the boys’ teachers at St. Andrew’s High School in Tonga recalled years later. “My students couldn’t get enough of it.”

So what happened to Peter and Mano? If you happen to find yourself on a banana plantation outside Tullera, near Lismore, you may well run into them: two older men, trading jokes, arms draped around each other’s shoulders. One the son of a big industrialist, the other from more humble roots. Friends for life.

After my wife took Peter’s picture, he turned to a cabinet and rummaged around for a bit, then drew out a heavy stack of papers that he laid in my hands. His memoirs, he explained, written for his children and grandchildren.

I looked down at the first page. “Life has taught me a great deal,” it began, “including the lesson that you should always look for what is good and positive in people.”

Rutger Bregman is a Dutch historian, a journalist, and one of Europe’s most prominent young thinkers. His last book, Utopia for Realists, which was translated into 32 languages, was a New York Times bestseller.

From the book HUMANKIND by Rutger Bregman. Copyright © 2020 by Rutger Bregman. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

This article is featured in the November/December 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Part of the difference in outcomes from the true story and “Lord of the Flies” can probably be traced to cultural differences between British (or American) teens and Tongan teens. But I believe that the true determinant factor is the character of the physically largest and strongest boys. If they are personally fair minded mature leadership types, the group will probably respond in building a better society. But if they are immature bullies, then they are likely headed for hard times. This scenario plays out in American schools daily. Unfortunately, many students will follow a class clown because they think they’re less likely to be bullied. But I do think that in some cases a better result is being achieved in some schools by addressing bullying as an educational priority and by encouraging students to engage in working toward the positive results. A strong, mature group who stand together can work wonders.

There are good and bad . These boys were among the good guys. I had it as a set book at school – unfortunately Piggy reminded me and quite a few others of myself!

I got chills reading this account. What a perfect antidote to the cynicism I’ve half-heartedly tried to ward off for the last five years. Thank you for publishing it and thank you to Saturday Evening Post for not putting it behind a pay-wall. I will be sharing it widely with friends.

Well Howard for a start there were just two of us in the crew, we could both swim but didn’t need to as they rowed use close to the beach and waded ashore, and there is a still picture showing just that. None of the original film was lost the total film shot was 30 minutes. The original film was for a Sunday evening new magazine item and was successful.

John Carnemolla, cameraman, what IS your alternate story?

Interesting reading , Ruthger uses a fair bit of poetic license in his version of the Channel 7 crew. Being the cameraman on that particular story its interesting that I have a slightly different memory of those events.

Interesting story; i’d never heard of this at all. I think the boys’ experiences, and how they faced an enormous challenge should be a parable of how a polarized society could work. That is, if we let go of the original Lord of the Flies as our moral standard.