Shortly after graduating from Yale Law School in 1973 at the age of 27, Bill Clinton took out a pen and piece of paper and wrote down his most important life goals. “I want to be a good man, have a good marriage and children, have good friends, make a successful political life, and write a great book.”

Assessing how he fared decades later against those five missions, he was unequivocal with respect to the third: “No person I know ever had more or better friends.”

Although he would call upon many of those friends, one man in particular gave him the emotional life he most needed when he became the youngest ex‑governor in American history. In 1980, the voters of Arkansas rejected Clinton’s bid for reelection to the office he loved. He was only 34. His vision of a grand political career — which so many others believed would carry him to the White House — now appeared to be in tatters. He became depressed, convinced his career was over.

Even before the polls opened in November 1980, Clinton knew that two of his own decisions had imperiled his reelection bid: a steep new license tax he enacted that enraged every car and truck owner in the state, and his reluctant acquiescence to President Jimmy Carter’s decision to transfer Cuban refugees from the Mariel boatlift into northwest Arkansas. Nightly television reports led with the ensuing rioting and lawlessness, further alienating voters.

Ten minutes after the polls closed, Clinton knew his tenure was over.

In the early weeks after his defeat, Clinton tried to make sense of how everything had come undone so quickly. In dozens of calls to friends and acquaintances, he heard plenty of support and commiseration. But that didn’t change his view: His perfect career had been knocked off its trajectory. This time, he felt too depressed to chart a comeback.

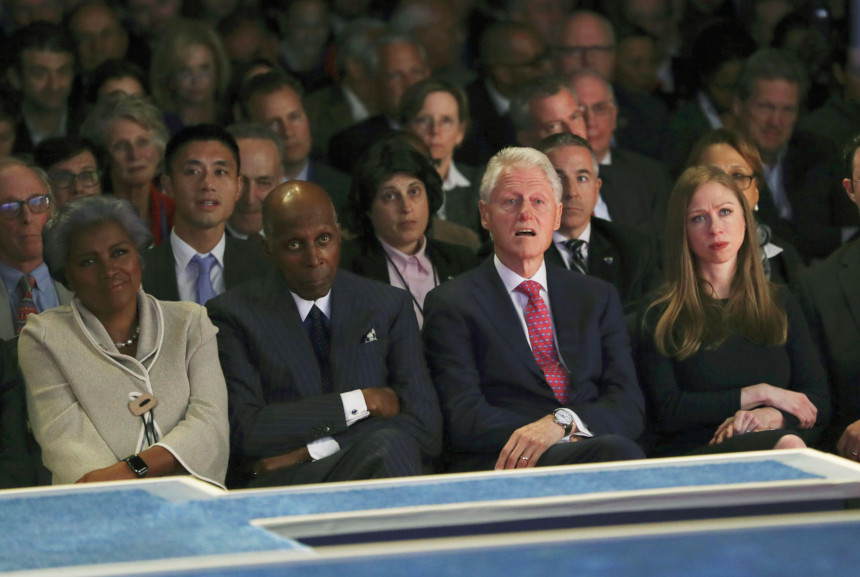

Vernon Jordan had watched the returns from his Fifth Avenue apartment in New York City on election night 1980. Ronald Reagan and his conservative Republican coalition swept the nation, winning the White House, flipping the Senate, and ushering in a generational realignment of American politics. Jordan was one of the nation’s most prominent civil rights leaders, and he was concerned what that rightward shift would mean for the future of a movement to which he’d dedicated much of his life. Amid all the carnage, one race in particular saddened him: the defeat of Bill Clinton in Arkansas.

The two men had met only three years earlier at a banquet for the National Urban League in Little Rock. Clinton then was the state attorney general, and Jordan was in town to raise funds for the powerful civil rights organization he had led for nearly a decade. Jordan had known of Clinton for years through Hillary, whom he met in 1969, minutes after Hillary had given a speech at an activist conference in Colorado. She was sitting on a park bench, going over the rest of the day’s schedule with Peter Edelman, a former Robert Kennedy aide, when “into my eyesight came a pair of highly polished shoes and a voice that said, ‘Well Peter, aren’t you going to introduce me to this earnest young woman,’” Hillary remembered. “I looked all the way from his shoes up to the head of this very attractive man. We started talking and instantly I was struck by his intelligence, his charisma and mannerisms. Just an incredible public presence. From that day forward we stayed in touch with each other until I introduced him to Bill years later. It was a mind meld between them from the get‑go.”

Forty-three years later, Bill Clinton vividly recalls the first time the two met: “The Urban League banquet was in a big school setting, inside a big gymnasium. We had a heck of a crowd there and he was a big star. The emcee for the evening was this woman who was one of our best TV anchors. She wore a beautiful dress that was high collared but had no back. Vernon and I were sitting on either side of the lectern where she was speaking, and her back was visible to Vernon. And he said to me after we were walking out, he said, ‘She’s a very attractive lady and that was a beautiful dress. It’s too bad they ran out of fabric before they finished it.’”

And so began Bill Clinton’s closest adult friendship — fittingly, in laughter, and not surprisingly about women, which would become a frequent topic of conversation. Over time, the bond would play a pivotal role at the most important moments of Clinton’s political and personal lives. When he thought about quitting politics, Jordan talked him out of it. A decade later, when he considered running for president, Jordan told him he was ready. Once in office, Clinton only had to say “Get Vernon” and Vernon would appear, asking for nothing in return. And then, when a sex scandal nearly ended Clinton’s presidency, Jordan was there to save his marriage and bolster his defense.

That single exchange back in 1977 presaged thousands of conversations and asides, some serious, others better left for the locker room, that would keep Clinton and Jordan engaged and entertained for the next four decades. Their banter would play out at Thanksgiving at Camp David and during Christmas Eve parties at the Jordans’ D.C. home; on Martha’s Vineyard for summer vacations and on golf courses across the country; in the Oval Office and upstairs in the White House residence.

As one former aide said, “They complemented each other perfectly: Both were extremely smart and charismatic; both were larger-than-life guys, with big appetites to do big and important things in life.”

Both Clinton and Jordan became transformational forces in their fight for racial equality: Clinton through sweeping reforms in the Arkansas legislature, Jordan through his legal and voter registration efforts in his native Georgia. Both men then made their mark on the national stage: Clinton as a progressive Southerner, Jordan as a moderate bridge builder to the white community.

Their shared commitment to racial equality was what initially united them, but the easy rapport and love of the game — especially politics and sports — took the Clinton-Jordan friendship to another level. The person who witnessed the friendship the most — Hillary Clinton — said that Jordan intuitively understood what “Bill, and any president, needs — someone they can just totally relax with, tell stories with, share a joke with, someone to just go out on the golf course with and not talk about anything of any significance if that’s what they choose. That’s what I thought was the incredible gift Vernon gave us over all the years we’ve known him.”

Both of them were operators, players. They knew how much each of them had benefited from their boundless charm and confident bearing. At 6 foot 2 and 6 foot 5, with broad shoulders and radiant smiles, Clinton and Jordan were keenly aware how much they lit up whatever room they occupied. When they turned those powers on each other the first night they met, the chemistry was electric. When Clinton later used that same magnetism on an intern in the White House, the effect would be equally electric but with devastating consequences.

By the time he dialed his defeated friend in December 1980, Jordan knew the soon‑to‑be-ex‑governor needed a stern talking‑to. Hillary answered the phone to a booming baritone of a voice. It was Vernon. “You got any grits down there?” Jordan asked.

“I don’t know how to make grits, but you come on down,” Hillary told him.

A few weeks later, Jordan stood in the tiny kitchen of the Clintons’ small yellow-framed house where they had just moved in after vacating the governor’s mansion. Awaiting him was a piping hot plate of instant grits Hillary had purchased that morning.

When he entered the cramped kitchen in his tailored three-piece suit and saw the young couple with their one-year-old daughter, Chelsea, Jordan could feel their despondence, especially from the ex‑governor. Gone was the confidence and verve that had so enchanted and impressed Jordan at their first meeting. He now saw sitting before him a diminished man carrying an overwhelming if irrational sense of rejection. Worse, he seemed lost, searching for direction but lacking will or a compass to steer himself.

Over the next two and half hours, Vernon Jordan’s regal presence dominated the small room. If ever there was a moment for Jordan to show his stuff, it was in that kitchen, at that table, as Bill Clinton wrestled with what to do next. Jordan knew he needed some straight talking. So he gave it to him in blunt, direct terms: Stop pitying yourself and appreciate what others see in you. You’re a man of immense promise who suffered a single setback, not a career-ending defeat. You have too much talent, too much commitment to the causes you care about, too much support to step off the stage and give it all up.

“He knew that I had just become the youngest former governor in the history of the country. And that my epitaph had been written,” Bill Clinton recalled. “He told me: ‘You and Hillary, you got a lot of talent, and your heart’s in the right place; it’s going to come out all right.’”

“Nobody else was saying that to me,” Clinton remembered 40 years later. “That wasn’t the storyline.” Jordan’s message resonated with Clinton at the very moment when he was seriously beginning to entertain offers out of state that would have given him better financial security and less heartache. “He told me I needed to stay in the game,” Clinton said. By this point, Clinton had been approached about becoming the head of the World Wildlife Federation, chief of staff to Governor Jerry Brown of California, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, or president of the University of Louisville.

Then Jordan appeared as the lone voice in the wilderness. “‘You’re not done, and you shouldn’t think you’re done,’” Hillary remembered Jordan saying as Bill ticked off the opportunities he was considering. “He made a big impression on him in that moment.”

Eventually, his message sank in. “I just took a deep breath and instead of being miserable, after that, it all began to sort of fall into place. And I began to just think about the rest of my life and try to live in the present and for the future.”

“That conversation was a milestone in Bill’s decision to stay in Arkansas, stay in politics, and ultimately to run for president,” Hillary said.

Before leaving for the Little Rock airport, Jordan offered one more piece of advice — for friend Hillary Rodham: She needed to start using “Clinton” as her last name. If Bill was going to make a political comeback someday, as he hoped, and do it in Arkansas, Hillary needed to accede to the conventions of the time and tone down her feminist rhetoric. As Bill recalled, “Vernon said to her, ‘I’m older than you are. I think keeping [the Rodham] last name is bothering a lot of older Black people and we need them all.’ And Hillary thought if Vernon believed she could do it and maintain her integrity and be who she was, it made her think she could do it.”

Hillary agreed: “It was important to have his voice in that decision. I respected his intelligence and political experience, and really paid attention to what he told me.”

On the heels of that pivotal conversation, Clinton went back to the voters of Arkansas, asking for their forgiveness and for another chance.

Two years later, on January 11, 1983, Bill Clinton, with Hillary Rodham Clinton by his side, took the oath of office as the 42nd governor of Arkansas. Amid the sea of thousands of onlookers massed at the front of the Capitol to see Clinton restored to power as the state’s favorite son was a smiling Vernon Jordan.

Gary Ginsberg has spent his professional career at the intersection of media, politics, and law. He worked for the Clinton administration, was senior editor and counsel at the magazine George, and has published pieces in the The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.

This article is featured in the March/April 2022 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Buddy system: President Clinton gets a pep talk after hitting a bad golf shot from “first friend” Vernon Jordan at the Farm Neck Golf Club on Martha’s Vineyard in 1993. (AP Photo / Marcy Nighswander)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Unsubscribe me. Your choice of this author and his exuberance over these two felons is remarkable. Horrible people do horrible things. Good Saturday Evening post.