If you were a bright, ambitious, young man in 1922 who wasn’t inconvenienced by your conscience, you might have considered starting your own liquor distribution business.

There were, of course, challenges: specifically, the 18th Amendment, Treasury Department officers, and, to a wildly unpredictable level, state and local law enforcement.

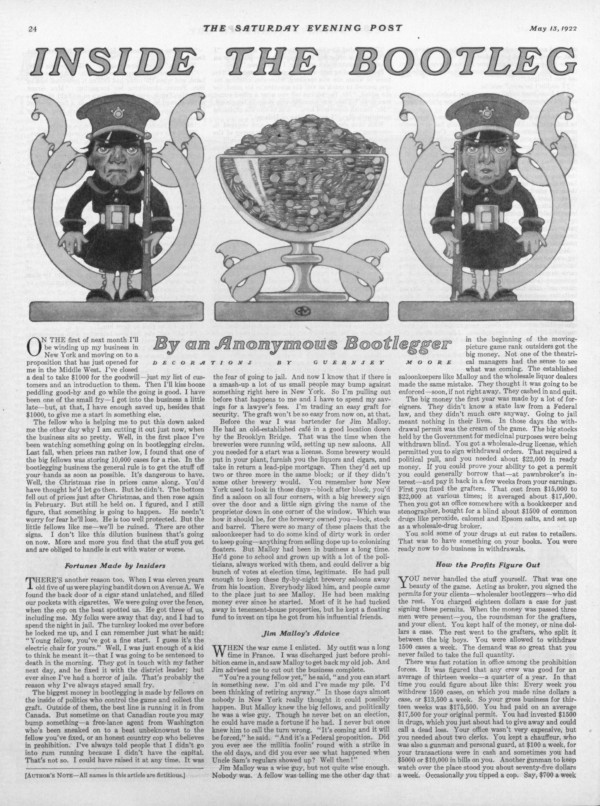

But in our May 13, 1922, issue, an Anonymous Bootlegger offered insider information to help ambitious entrepreneurs on their way to becoming the next Al Capone.

He discussed three promising business models: brokering legal “medicinal” liquor, driving liquor over the border from Canada, or bringing it by boat from overseas.

The Medicinal Whiskey Racket

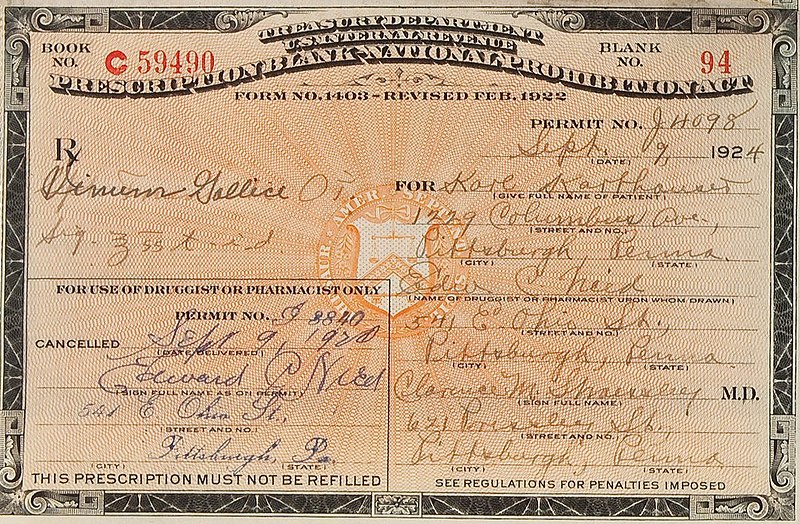

When prohibition began, the government took all alcohol off the market and put it in secure storage. However, it permitted some of the whiskey to be released as a prescribed drug. In 1922, doctors could write a one-time “prescription” for a “patient” who could take it to a drug store. There, they paid $3.00 ($40 in today’s money) for one pint of whiskey. The next week, they could go back to the doctor and get another prescription.

The key to entering this business, said Mr. Bootlegger, was to find a government official willing to sell you a “wholesale-drug license.” One could expect to pay $22,000, he said, but the price wasn’t a deterrent. If an applicant could prove to a banker that they could actually buy a license, the banker would make the loan, knowing it would be repaid in a few weeks.

Next, one would need to pay off a number of officials, which could include anyone from warehouse security guards up to city and state prosecutors. Mr. B. put the amount at around $17,500.

After that, it was time to get an office, a bookkeeper, and a secretary, then sell some legal, cut-rate pharmaceuticals to a supplier to create a record of legitimate business.

Last was the meeting with a wholesale bootlegger. In return for a signed alcohol-withdrawal permit, the wholesaler paid $18 a case and the broker kept $9 of that amount. The rest went back to the paid-off officials who “split it among the big boys.” At the best of times, a bootlegger could sign withdrawals for 1500 cases each week.

Here were Mr. Bootlegger’s quarterly figures for this operation:

Original graft payment: $17,500

Legitimate drugs for your “front”: $1,500

Office expenses and guards: $9,000

Total: $28,000

Gross receipts for 13 weeks: $175,500

Expenses: $28,000

Net Profits: $147,500 (= the 2022 purchasing power of $2.5 million)

It was a sweet setup — while it lasted. Unfortunately, by 1922, it had all folded up in New York. An official from Washington cleared out all the corrupt office workers. Now, instead of 60 withdrawal permits, only 20 were given out. And the amount of daily alcohol withdrawals has been cut from 15,000 to 366 gallons.

The Canadian Express

Before and after the First World War, Mr. Bootlegger was a bartender in a fashionable New York saloon. Prohibition put him out of work, but many of his former customers were well connected in the now-illegal liquor business. They encouraged him to branch into bootlegging.

He began by finding a steady market — a large New York business whose workers knew him when he was a bartender. He arranged with its management to be the building’s exclusive source of liquor for the workers.

He began driving a truckful of liquor from Canada into New York, hiring two guards and a driver for a truck. He would follow in his car from a distance in order to surprise anyone trying to hijack the truck. Here were his expenses:

Hire of two guards and a driver: $120

Gas, oil and incidental vehicle expenses: $100

Bribes for local or border police: $10-$20

The case price for his liquor once it entered the U.S.: $60

Selling price: $90 for bulk sale, $95 for sale in small lots

Total profit: $30 a case or $1500 for a 50-case load

There could be large, unexpected expenses, such as the truck being stolen or hijacked. And an arrest meant $10,000 in legal fees, the equivalent of up to three months of work.

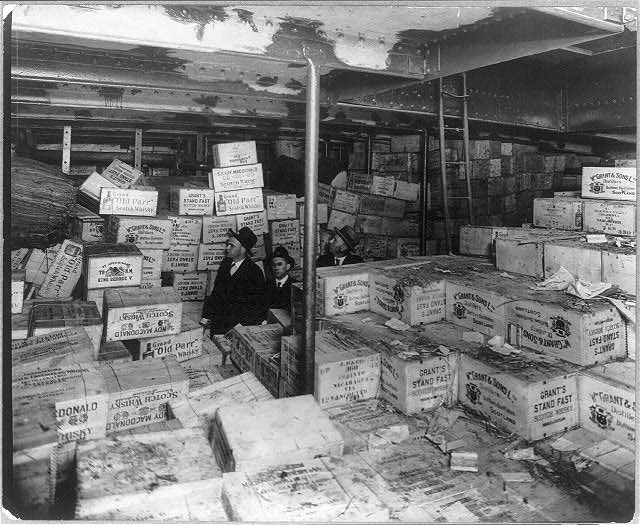

Rum Running

Rum running was another lucrative venture, but it was expensive. One could drive liquor in from Canada for about $2,500; bringing in liquor on a boat could cost up to $200,000, according to Mr. Bootlegger. But an experienced smuggler could sell 500 cases a day off his boat. The annual income of a rum runner could be more than $100,000.

Mr. Bootlegger didn’t know exactly how profitable it was, but he said it had to be lucrative because more and more of New York’s alcohol was coming by sea.

“Charlie Sent Me”

There was a fourth business model, but the bootlegger didn’t recommend it. Simply opening your own speakeasy avoided the hassle of buying, selling, and moving, but there was little chance of surviving on the profits from a single property: one raid and everything was lost. And there was a good chance this would have happened to a small-time operator. In a 1926 article in the New Yorker, a bootlegger wrote, you can be shut down if you “make a policeman mad, or fail to pay a prohibition agent as much as the agent thinks he deserves.”

Most “speaks” were operated by syndicates, he said, which had powerful connections. There were 32 speakeasies in one block, between Fourth and Fifth Avenues in New York City, and 25 were owned by one firm. They had money enough to survive the closing of one of their establishments.

Customers Are Losing Their Taste

Regardless how you dealt in prohibited liquor, the Post’s Bootlegger said, you’d confront one constant in the business: “the average customer has ten dollars fixed in his mind as about the price he’d willing to pay for a bottle of whiskey.” So if a bootlegger couldn’t sell his whiskey at a profit for ten bucks, he’d dilute his stock with distilled water until he could.

Fortunately, after two years of prohibition, customers no longer remembered what real, undiluted whiskey tasted like, and were usually happy with any good imitation.

Leaving You with a Warning

At the beginning of his article, Mr. Bootlegger declared that he was selling his contacts and “good will” and leaving the bootlegging game for legitimate employment. He’d learned someone was storing 10,000 cases of whiskey and refusing to sell any. He expected this person would sell off at some point, flooding the market and dropping the price of liquor so low it would drive the little bootleggers out of business. And he emphasized, more than once, that the real money in bootlegging went to politicians and gangsters — people who never even got close to the liquor.

He left no doubt: the greater your risk, the smaller the cut of the take.

Featured image: New York City Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach, right, watching agents pour liquor into sewer following a raid ca. 1921 (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I read the 1922 article. Fascinating, but no. No thank you. I don’t want to be a bootlegger, at all.