This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Cities, towns, and communities all across the United States have hosted July Fourth festivities this week, but only one can accurately lay claim to “America’s Oldest Fourth of July Celebration!” That’s Bristol, Rhode Island, a small town just across the border from Massachusetts that began hosting its “Patriotic Exercises” while the American Revolution was still being fought. Those Exercises continue to this day, and have evolved into a multi-week celebration that begins on Flag Day, features many other events including fireworks of course, and concludes with the longstanding 2.5 mile Military, Civic, and Fireman’s Parade on the Fourth itself.

The Fourth of July is a profoundly symbolic occasion, an opportunity for celebratory patriotism that has the potential to genuinely connect all Americans to a sense of love for our shared community. But it’s also an important moment for the tough love that I call critical patriotism, for recognizing and challenging the gaps between our national ideals and the realities of our histories, including the oppressive and violent events that have been far too foundational and endure into this celebratory week. And in two key ways, Bristol reflects and embodies those much more painful histories, offering us an exemplary lens through which both to remember those crucial contradictions and to continue the fight for a more perfect union that includes all Americans.

The first of those two histories is Bristol’s central role in the slave trade, which emerged at precisely the same time the community was beginning to present those Fourth of July celebrations. In Unrighteous Traffick, a series of 15 compelling articles for the Providence Journal in 2006, journalist Paul Davis offered a comprehensive history of Rhode Island’s central role in the slave trade across the entire 18th century. As Davis puts it, “Rhode Island ruled the slave trade. For more than 75 years, merchants and investors bankrolled 1,000 voyages to Africa. Their ships carried some 100,000 men, women, and children into New World slavery.”

Bristol was far from alone, but it emerged as the center of the trade at a particularly fraught moment, in the post-Revolutionary period when Rhode Island had officially outlawed slave trading. As Davis notes, “almost half of all of Rhode Island’s slave voyages occurred after trading was outlawed [in 1787]. By the end of the 18th century, Bristol surpassed Newport as the busiest slave port in Rhode Island.” Those final decades of the century were the origin of the period known as the Golden Age of Sail, and a significant number of the voyages departing from and arriving at every American port in the era were intertwined with slavery through economies like the Triangular Trade. But in Bristol the connections to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade were much more overt and central.

Of the countlesseffects of that post-Revolutionary slave trade in Bristol, one of the most striking is how much it built the city’s great fortunes and families (as was the case in Newport as well). Exemplifying that trend is the story of the multi-generational DeWolf family that came to be synonymous with Bristol and even Rhode Island itself. As Davis writes, “the DeWolfs financed 88 slaving voyages from 1784 to 1807 — roughly a quarter of all Rhode Island slave trips during that period.” They used their profits to construct the city’s emerging infrastructure, as with their 1797 founding of the Bank of Bristol with $50,000 in capital. And they brought their family clout with them to Washington, D.C., where the brutal slave trader James DeWolf (at one time the second richest man in America) built on his career as Speaker of the Rhode Island House by becoming a U.S. Senator in 1821. In so many ways Bristol was crucial to America’s growth after the Revolution, and in every way it was tied to the slave trade.

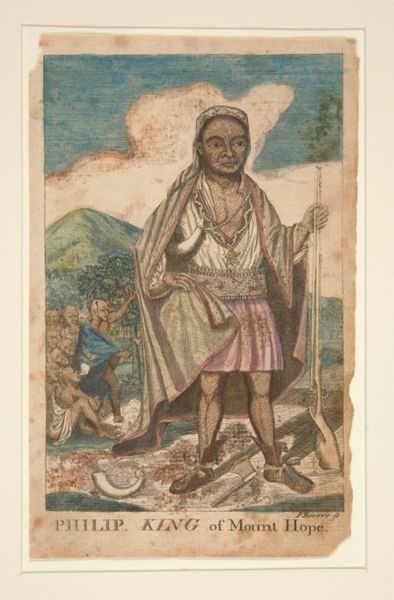

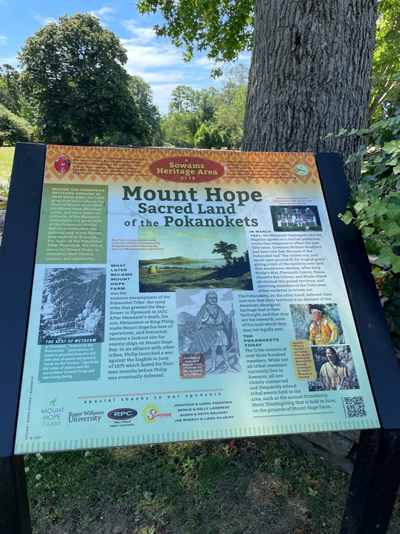

Bristol is also intertwined with the even more foundational American history of violence through its role in the brutal late 17th century conflict between the English and the Wampanoag known as King Philip’s War. Long before English settlers arrived in the region, it was a particularly sacred homeland for the Pokanoket Tribe: named by the Pokanoket as Montaup (Mount Hope in English), these thousands of acres on the shores of Narragansett Bay were the social and spiritual heart of the area known as Sowams. Pokanoket chief Massasoit was the leader who greeted the Mayflower arrivals in 1620 and signed an important peace treaty with them the following year, and his son Metacomet (King Philip) would make Mount Hope his social and military base of operations, featuring the rocky ledge known as “King Philip’s Chair.”

King Philip’s War was caused by numerous historical and cultural factors, and over nearly 14 devastating months its battles and other prominent events would span much of New England. But at its heart, the war represented a desperate attempt by Metacomet and the Pokanoket to respond to the increasing English incursions onto their tribal and sacred lands like Mount Hope. In the early days of Plymouth Plantation its Governor William Bradford learned that the Pokanoket land “had the richest soil, and much open ground fit for English grain,” and for the next half-century English settlers from Plymouth, the Massachusetts Bay colony in Boston, and elsewhere would gradually take more and more of that land in fraught “sales” that too often seemed to reflect swindling of natives. By the time Metacomet became the tribal chief in 1666, virtually all of the land surrounding Mount Hope Neck was English property.

Both King Philip’s War and Metacomet’s life would end in Bristol, not far from his Chair. On August 12, 1676, Metacomet and a band of warriors were ambushed at Mount Hope, and he was murdered by English soldier Caleb Cook and Pocasset warrior John Alderman, a Native American working with the English. The English would then brutally mutilate Metacomet’s corpse: quartering his body, mounting his skull on a pole near Plymouth Plantation, and sending his lower jaw bone to Boston for public viewing. The site of Metacomet’s murder is preserved deep in the Bristol woods near Mount Hope Farm, as is the ledge that served as his Chair, both significant historical landmarks that are far too easily overlooked, both part of lands that the Pokanoket continue to claim sacred stewardship over here in the 21st century.

In downtown Bristol, right along the route of the July Fourth parade, can be found the beautiful and moving Memorial Garden, one of America’s most striking tributes to a community’s history of military service and sacrifice. The thousands of veterans’ names on the Garden’s memorial wall reflect the city’s history of active patriotism in service of the nation’s ideals. But critical patriotism demands that we remember as well the histories of oppression and violence that helped build the city, as they did the nation. Bristol and America have just commemorated another Fourth of July; it’s more important than ever that we engage with all these crucial contradictions.

Featured image: Bristol, Rhode Island, Fourth of July parade (Kenneth C. Zirkel via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This article is typical of leftist rhetoric that unlike most healthy nations seeks to permanently identify the United States with its worst moments. Moments which “every”nation has, but most choose to recognize but to grow beyond.

I have noted this trend of late in the Post. Sadly typical of our media.

Thanks for the comment, and sounds like an important lecture, Keith! These columns are never every part of the story nor of our histories–but I do believe they are parts we should all better remember, as I’m sure were the subjects of your talk as well.

Take care,

Ben

Maybe the author should have attended my lecture at the Bristol Fourth of July Committee Interfaith Service in advance to the 2022 parade to receive a full recognition of our African heritage and history in Rhode Island. As my Newport grandmother would remind me as a boy, “Slavery is how we got here, but it tells you little to who we are as a people.”