Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence and Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments open with exactly the same phrase, save Stanton’s insertion of two words: “and women.”

The Declaration of Sentiments was presented by Stanton and her co-authors at the Seneca Falls Convention — the first women’s rights convention in the U.S. — which took place July 19 and 20, 1848, at Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York. The document borrowed Jefferson’s words, declaring, “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” It was signed 174 years ago today.

The Declaration of Sentiments’ invocation of Jeffersonian language was meant to imbue the women’s rights movement with the same ideas of freedom the nation already held dear. The fact was, the rights laid out in Jefferson’s 1776 Declaration applied to less than half of the United States populace. In the mid-nineteenth century, the U.S. government and society as a whole believed women to be lesser people. As Stanton wrote in the Declaration, men held women in “absolute tyranny.” Married women were not allowed to own property or money, women were restricted from university education, and no woman was able to vote. Female responsibilities were in the home: raising children and tending to husbands.

A paradoxical “moral” motivation was behind some of the misogyny. If restricted to her home and barred from civic life, a woman could be protected from the evils of the outside world. In that home, women were expected to participate in the “cult of domesticity,” using moral aptitude and piety to raise virtuous boys who would then enjoy a democratic power their mothers never could.

Stanton was a prominent intellectual, and though she’s lesser known than collaborator Susan B. Anthony, her efforts toward women’s suffrage and the United States women’s rights movement are significant. Born in 1815 in Johnstown, New York, to an aristocratic family, Stanton began her intellectual career early with an education at Johnstown Academy and at Emma Willard’s Troy Female Seminary. The Seminary was the first higher education institution for women in the country; it provided an education comparable to universities, which were available only to men.

On her honeymoon in London, Stanton attended the 1840 World’s Anti-Slavery convention, where she found herself disallowed from proceedings on account of her sex. Also excluded was abolitionist and feminist Lucretia Mott, with whom Stanton discussed women’s rights and a potential convention in the United States. Eight years later that convention was held in Seneca Falls, and it became the moon to draw up the United States’ first feminist wave.

Along with Stanton and Mott, the convention’s organizers included Mary M’Clintock, Jane Hunt, and Martha Coffin Wright. To ensure a productive conversation, the Seneca Falls Convention was split into two days: the first open to women only and the second inclusive of male participants. About 300 people attended, many of them Quaker women from the area.

The events of July 19 were mainly readings of feminist articles and discussion, as well as a reading and deliberation of the Declaration of Sentiments among first-day attendees. On the second day, Stanton read the Declaration of Sentiments to an audience of women and men. The Declaration included a preamble discussing the necessity for change and demonstrated this with a list of 19 “injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman.” These included the lack of rights afforded to married women, the inequality women were afforded in the justice system, the absence of women’s access to college education, and others. Most significantly, the first four injuries were related to elective franchise, the right to vote in elections of public officers.

Following the list of injuries, Stanton read the Declaration of Sentiments’ 12 resolutions, which declared various goals and statements by which the women’s rights movement would orient its platform. For example: “Resolved, That woman is man’s equal — was intended to be so by the Creator, and the highest good of the race demands that she should be recognized as such.” Each was passed unanimously by conference participants except for the ninth: the right of women to vote.

A woman’s right to vote had, until the Seneca Falls Convention, been more a dream than an actual goal of feminists. Many attendees initially opposed women’s enfranchisement, including Stanton’s husband, thinking women’s suffrage was unrealistic or unnecessary and the activists would be laughed at for suggesting something so silly. Though Stanton was not the first women to publicly approach the issue of suffrage — just two years prior, six property-owning women submitted a petition to the New York State Constitutional Convention asking for equal civic rights and were denied on the grounds that a woman’s right to vote was unnecessary — her refusal to back down from demanding suffrage at the convention forced it into the public eye. After debate, the ninth resolution did pass, and the Declaration was signed by 68 women and 32 men on July 20, 1848.

When drafting the Declaration of Sentiments, Lucretia Mott’s initial response to Stanton’s ninth resolution was: “Why, Lizzie, thee will make us ridiculous.” This was not because she didn’t believe women’s suffrage was necessary, but because she correctly predicted a negative public response to its suggestion. As Stanton wrote in her memoir, “All the journals from Maine to Texas seemed to strive with each other to see which could make our movement appear the most ridiculous. … So pronounced was the popular voice against us, in the parlor, press, and pulpit, that most of the ladies who had attended the convention and signed the declaration, one by one, withdrew their names and influence and joined our persecutors.” While some newspapers, such as Frederick Douglass’ The North Star, praised or at least acknowledged the convention as legitimate, most ridiculed it.

Opposition to women’s rights was not restricted to male critics. Many women would fight against enfranchisement later in the suffragist movement, citing consequences impacting the comfort of their roles in the home. In a pamphlet issued in 1914, the Nebraska Association Opposed to Women Suffrage detailed their reasoning. One of their ten points was, “Because in political activities there is constant strife, turmoil, contention and bitterness, producing conditions from which every normal woman naturally shrinks.”

While the organizers of the Seneca Falls Convention would not live to see their goals realized, they played an enormous part in catalyzing the women’s suffrage movement. The press surrounding the convention, though mainly negative, nevertheless drew unprecedented national attention to their efforts. The suffragists gained numbers and, by the early twentieth century, were holding regular protests and further organizing for their rights. In 1920, the 19th Amendment was passed, which gave women the right to vote.

Many have correctly criticized Seneca Falls-era feminism for its makeup of almost exclusively white, non-poor women and its prejudices against other groups. While Stanton and her colleagues were active abolitionists, some of their beliefs — reflective of era, race, and class — were flawed. When the 15th Amendment granted suffrage to Black men in 1870, many suffragists, including Stanton, either implied or said outright that Black men were less qualified to vote than white women because of perceived inferiority, using racism to promote their own interests.

The effects of the 1848 convention, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and her contemporaries, though, are incalculable. The Seneca Falls Convention popularized the U.S. women’s rights movement, and because of it, American feminism has progressed through a second, third, and current fourth wave, becoming more nuanced with each passing decade.

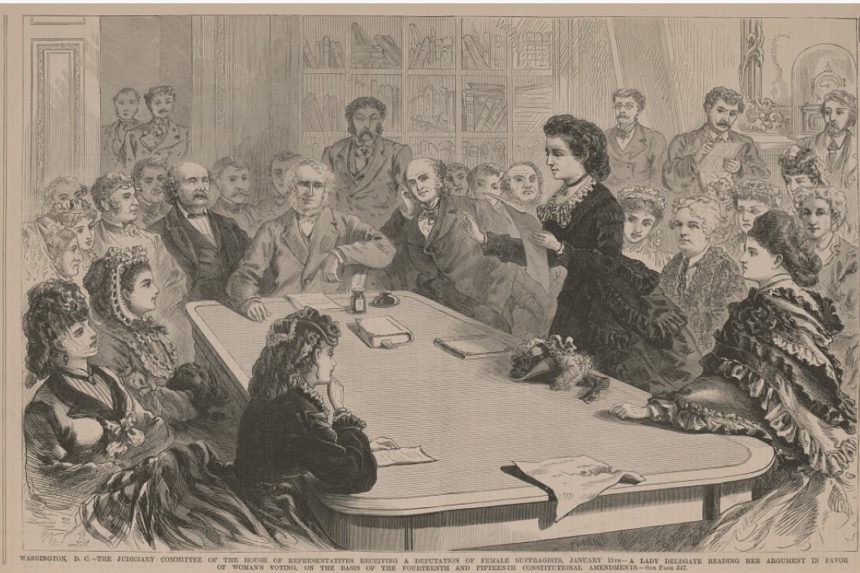

Featured image: In Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, an illustration of a suffragist addressing Congress. The caption reads: “The Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives receiving a deputation of female suffragists, January 11th — a lady delegate reading her argument in favor of woman’s voting, on the basis of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Constitutional Amendments.” (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Really excellent feature, Ms. Anderson. Things are moving backwards in regards to women’s rights and autonomy. I’m hoping against hope we’re going to be getting a woman President sooner than later (waaay overdue) but must be the right (as in best) woman that will do what’s right for women, the environment, and help all Americans during this edge-of-the-cliff time for the U.S., and the world. A woman that will be a force to be reckoned with here, and on the world’s stages before it’s too late. Until then, we have to bide our time with whom we have.

Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results is the very definition of insanity. Women historically have saved the day from the stupidity of men many times. Let’s get HER in the White House in 2024 without further ado, my fellow Americans!

It still amazes me how despite this pivotal event happening in 1848, it would still be over 70 years until women would even gain the right to have a say in how their government impacts their daily lives. It also amazes me how we seem to be going backward in regard to women’s rights and autonomy at the moment. It is an on going struggle that has everything to do with control and politics and nothing to do with what is right.