This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This past week the President of the American Historical Association, Professor James H. Sweet, created a great deal of controversy around the concept of “presentism” in the study of history. In “Is History History?,” his latest “From the President” column for the AHA journal Perspectives, Sweet criticized what he saw as the “trend toward presentism” within “the entire discipline,” complaining about the practice of “reading the past through the prism of contemporary social issues” such as “race, gender, sexuality, nationalism, capitalism” and arguing that “this new history often ignores the values and mores of people in their own times, as well as change over time.”

Sweet and his controversial column have already prompted a number of impassioned rebuttals, such as Kevin Gannon’s multi-layered response which concludes by noting that “Sweet’s article does render at least one service to the profession: it reminds us that the strongest expression of ‘identity politics … is a privileged white man condemning what he sees as everyone else’s obsession with ‘identity politics.’” I’m not looking to add here to that backlash against this individual voice and piece, backlash which has already prompted the apologetic Author’s Note with which Sweet’s column now opens.

But the central tenets of Sweet’s definition of presentism, the idea that “people in their own times” were fundamentally different from those in our own and that the prism of contemporary social issues constitutes our modern perspective rather than ideas and debates found throughout history, reflect a widespread and inaccurate view of the past. Offering a vital counterpoint to that view is the case of Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Banneker.

In this Considering History column I highlighted Jefferson’s consistent prejudice toward African Americans, bigoted views expressed in Notes on the State of Virginia (1785). In a book defined by its nuanced and thoughtful natural and scientific observations, Jefferson’s infamous passage that “the blacks are … inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind” stands out as even more discriminatory and egregious. While certainly such blatant racism was part of Jefferson’s “times,” this was a man who prided himself on his independent thinking, and one whose extensive, profoundly personal experiences with African Americans must have belied his odious ideas about their “transient griefs” and “dull, tasteless, and anomalous” imaginations.

The enslaved, Revolutionary African American activists and patriots I discussed in this column reflect just how much Jefferson’s own times featured challenges and alternatives to his prejudicial views. The enslaved petitioners who presented their case for freedom to the Massachusetts Legislature in January 1777 made clear that the griefs entailed in being “detained in a state of slavery in the bowels of a free and Christian country” were anything but transient. And the beautiful, stunning Revolutionary poems of the teenage enslaved poet Phillis Wheatley reflected an American literary and political imagination that was the furthest thing from dull or tasteless (despite Jefferson’s bigoted dismissals of her works). Moreover, all these African American activists and authors found contemporary supporters and allies, white Americans whose inclusive views and actions were just as much part of their own times — from lawyers like Theodore Sedgwick and Tapping Reeve who helped enslaved people like Elizabeth Freeman fight for their freedom, to the radical journalist Tom Paine who published Wheatley’s poetry in his Pennsylvania Magazine.

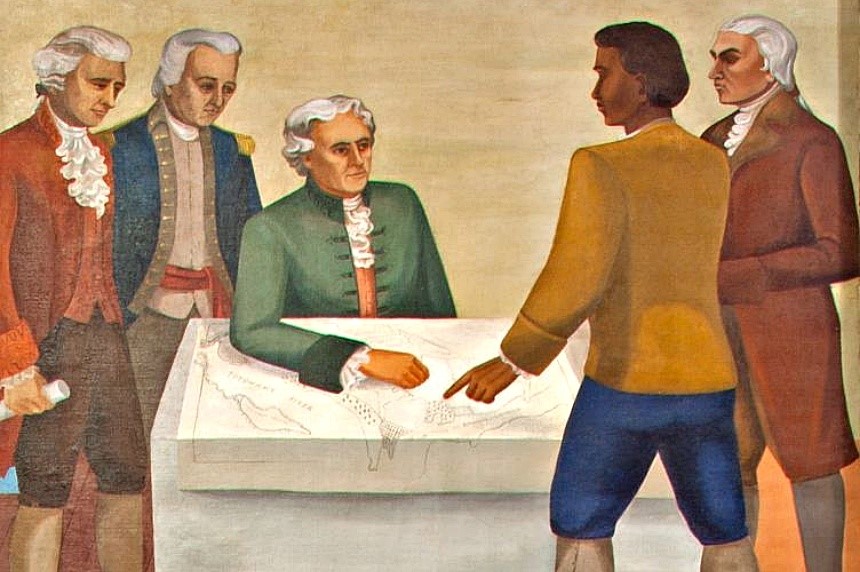

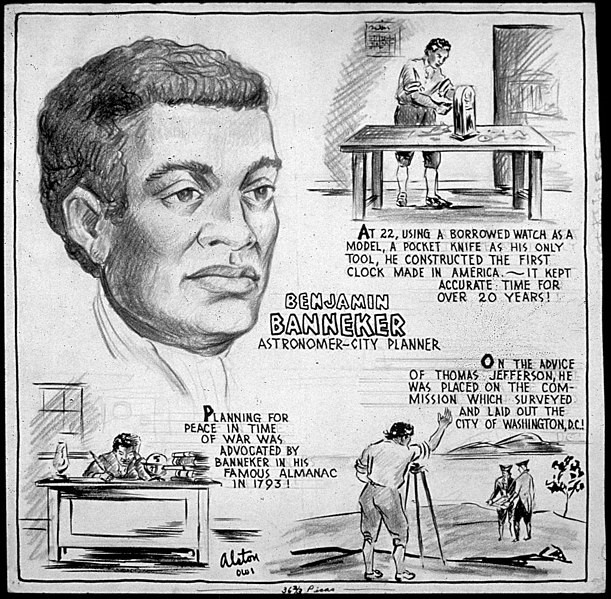

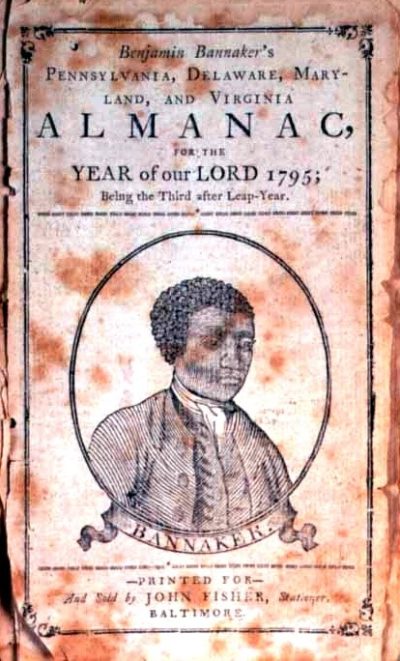

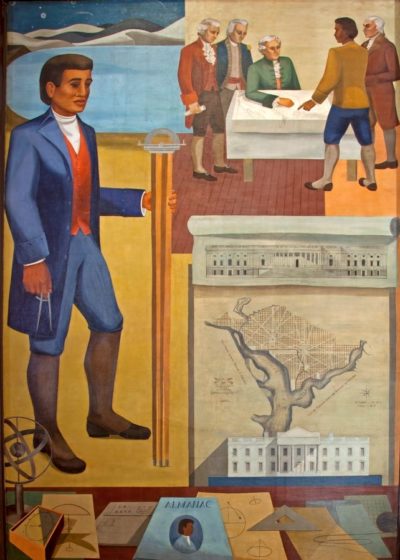

It’s not simply that the period featured such alternatives to Jefferson’s racism, however — it most strikingly featured, in the African American scientist and mathematician, farmer and surveyor, author, and activist Benjamin Banneker, a figure who wrote to Jefferson to directly and convincingly challenge that racism. Born free in November 1731 to a formerly enslaved father and a mixed-race mother who together owned and operated a 100-acre tobacco farm in Maryland, Banneker grew up to be one of 18th century America’s most learned, successful, and impressive Renaissance people. By the time Jefferson published Notes on the State of Virginia, Banneker had already become a self-taught, accomplished mathematician and astronomer; over the next few years, he would serve as a principle surveyor for the mapping and development of Washington, D.C.

During that same period, in the summer of 1791, Banneker read Jefferson’s racist speculations in Notes and made the bold and inspiring decision to push back on them directly in a letter to Jefferson. Jefferson was by this time serving as America’s first Secretary of State, making Banneker’s choice to offer this written rebuke to one of the young nation’s most prominent and powerful figures even more striking. Banneker acknowledges that fact, among other obstacles facing him, in the letter’s self-reflective opening paragraph:

I am fully sensible of the greatness of that freedom which I take with you on the present occasion; a liberty which Seemed to me scarcely allowable, when I reflected on that distinguished, and dignified station in which you Stand; and the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion.

But having taken that freedom and liberty — terms that seem quite resonant indeed for the letter’s moment, subjects, and audience alike — Banneker certainly made the most of the occasion. Appealing to Jefferson both personally, as “a man far less inflexible in Sentiments …

than many others,” and politically, as part of the Revolutionary generation who “were then impressed with proper ideas of the great

valuation of liberty,” he makes the case for both freedom and equality for all of Banneker’s African American brethren. He recognizes how long and fully “the abuse and censure of the world” have targeted his “race of Beings,” and uses religion, science, logic, emotion, and the example of his own identity and perspective to challenge those prejudicial views. Begging Jefferson “and all others to wean yourselves from these narrow prejudices which you have imbibed,” Banneker makes an impassioned and convincing argument for a post-Revolutionary America in which he and all African Americans can have a genuine and meaningful place.

Jefferson’s response to Banneker’s letter, and to the self-published almanac that Banneker sent along with it, was mixed at best. He initially responded politely and praised Banneker’s accomplishments; but he later expressed doubt that Banneker was the almanac’s actual author and reiterated his racist, hierarchical views. In such beliefs, as well as in the horrific practices of slavery in which he took part throughout his life, Jefferson remained to be sure very much part of the dominant white supremacist structures of his era.

The key takeaway is this: Jefferson’s era was also Banneker’s era. That crucial fact was not lost on their contemporaries: writing of Banneker’s role in the Washington, D.C. survey, the Georgetown Weekly Ledger praised “Benjamin Banniker [sic], an Ethiopian, whose abilities, as a surveyor, and an astronomer, clearly prove that Mr. Jefferson’s concluding that race of men were void of mental endowments, was without foundation.” What was and is foundational instead is the role of African Americans like Banneker in the nation’s Revolutionary and framing periods. Benjamin Banneker was a person of his times, reflecting the central presence of race, racism, and debates over such shared social issues that existed in Banneker’s present just as much as our own.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now