This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On January 17, 1893, a military force featuring more than 160 Marines and sailors from the warship USS Boston took part in a coup to overthrow Hawaii’s Queen Lili’uokalani and install a new provisional government led by U.S. businessmen and their political allies. Even though the president of the United States, Grover Cleveland, publicly opposed the coup, those U.S. armed forces comprised just one element of a multi-faceted American involvement in and support for this hostile and illegal action against the Hawaiian government. The coup succeeded, establishing an interim Republic of Hawaii that governed only until the federal government formally annexed the islands as a United States territory in 1898.

To most 21st century Americans, Hawaii is a tropical paradise, a vacation destination full of spectacular vistas, thundering surf, and threatening volcanoes (and the birthplace of the 44th president). But how that paradise became part of the United States is a long, complex, and often dark story, one that illuminates how the expanding nation, and the political, military, and corporate forces driving that growth, engaged with local and indigenous leaders and communities.

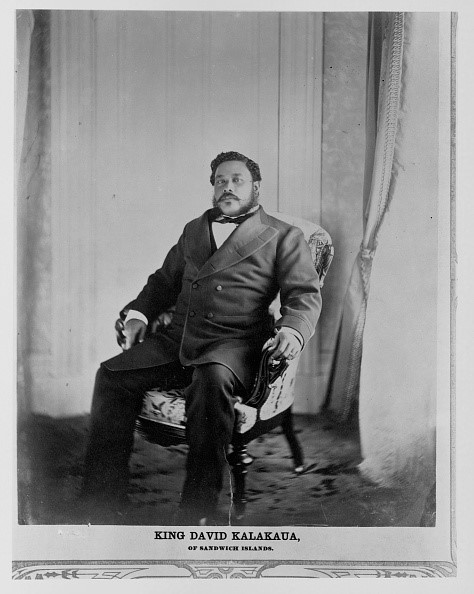

Throughout the 19th century, the United States government’s relationship with Hawaii was influenced by three powerful and interconnected forces: Christian missionaries seeking to convert the island’s inhabitants; business leaders seeking to gain control over its abundant sugar crops; and military forces allied with those groups and seeking a Pacific base from which to better protect the Western United States. All these groups maintained uneasy relationships with Hawaii’s indigenous leaders, monarchs from the Kamehameha Dynasty that had ruled since Kamehameha I took the throne in 1795. Despite the U.S. formally recognizing an independent Hawaiian nation in July 1846, missionaries, businessmen, and military leaders continued at the very least to seek a foothold in, and ideally to gain control over, the islands in order to advance their respective interests. When King Lunalilo died without an heir in 1874 and a new ruler, David Kalākaua, was chosen by the Hawaiian legislature, these American forces saw an opportunity to consolidate their power.

American figures like missionary Charles Reed Bishop, military leader Major General John Schofield, and businessman Sanford Dole lobbied the federal government to pressure King Kalākaua, hoping to force him to surrender portions of the islands (like Pearl Harbor and Ford Island) to the United States for military and business uses alike. Those figures, working with a Hawaiian-born child of missionaries and influential lawyer and publisher named Lorrin Thurston, formed a new group known as the Hawaiian Patriotic League to further advance their goals. Kalākaua was able to resist them and maintain power for more than a decade, but in July 1887 the League drafted a new Constitution (written by Thurston) and forced Kalākaua, under threat of assassination, to sign it. Known as the “Bayonet Constitution,” this document not only dissolved much of the existing government and granted significant new powers to the League and their allies, but also disenfranchised both indigenous Hawaiians and Asian immigrants to the islands in favor of white Americans.

When Kalākaua died in 1891, his sister, Lili’uokalani, took the throne as the first Queen of Hawaii. Lili’uokalani had previously been approached by the League with offers to replace her brother, but she had resisted, believing they would use her as a figurehead to further minimize the power of the monarchy and the indigenous community alike. When she thus became Queen through more legitimate means, she worked instead to reestablish that power, going so far as to propose a new Constitution in late 1892 (to go into effect in early 1893) which would have eliminated property requirements for voting, lessened the political and social privileges granted to American residents and businesses, and redressed the balance of government and rights alike in favor of indigenous and Asian residents. Lili’uokalani traveled the islands on horseback to make the case for her Constitution, gaining a great deal of local support and raising concurrent concerns from the League and their allies.

To symbolically express those concerns, 13 particularly powerful members of the League dubbed themselves a Committee of Safety. Led by Thurston and lawyer Henry Cooper, the Committee began amassing weapons and resources with which to overthrow Lili’uokalani and formally take control of the Hawaiian government. When Marshal of the Kingdom and Lili’uokalani ally Charles Wilson learned of the plot and sought to thwart it, the Committee resorted to violence. On the morning of January 17, 1893, Committee member John Good shot an indigenous policeman named Leialoha who was trying to seize a shipment of weapons. The Committee used the incident as a justification for putting their plan in motion. Cooper assembled a crowd in front of the royal palace and read a proclamation formally deposing Lili’uokalani and establishing a provisional government led by President Sanford Dole.

Lili’uokalani vocally and passionately protested, issuing her own January 17th proclamation to Dole that read in part,

I Liliʻuokalani, by the Grace of God and under the Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the Constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a Provisional Government of and for this Kingdom.

She added,

Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

U.S. President Grover Cleveland did indeed recognize these events for the illegal coup that they were, later telling Congress in his State of the Union address that “the military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war” and refusing to annex the islands into the U.S. But many other U.S. political and military leaders disagreed and took active part in this coup and its aftermath. The prior administration’s Secretary of State, John Foster, had worked closely with the Committee of Safety on their plans. The chief American diplomat in Hawaii, John Stevens, was convinced by the Committee of the need for the coup and agreed to send in the Marines and sailors from the Boston in support. And despite Cleveland’s ongoing opposition, President Dole continued to govern the newly created Republic of Hawaii until Cleveland’s successor, U.S. President William McKinley, signed a formal agreement to annex Hawaii into the United States in July 1898.

As I wrote in my last Considering History column, we’ve talked a great deal in recent years about coups in U.S. history. But the U.S. government hasn’t simply been the target of such coups — it has also worked to overthrow other sovereign governments, especially those of indigenous communities whose lands U.S. settlers and interests desired. The events of January 17, 1893, in Hawaii offer a particularly striking illustration of those consistent and deeply unsettling American histories.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Charles Reed Bishop was not a missionary descendant. And exhibit hosted by The National Portraits gallery in Washington D C. features information about the United States, the Spanish American war, and the territories acquired as a result of the war. The exhibit is named

1898 U.S. Imperial Visions and Revisions

Thanks for the thoughtful comments and additions, all. I wanted to note that at the end of a recent weeklong blog series on this column’s 5-year anniversary, I paid tribute to one of y’all, Bob McGowan–but very much as an example of the excellent contributions of many commenters over the years:

http://americanstudier.blogspot.com/2023/01/january-14-15-2023-five-years-of.html

Thanks again and keep ’em coming!

Ben

The US marines participated in the coup against the Hawaiian monarchy. When the republic had a vote to agree to join the US as a territory, the native Hawaiians who were a majority of the population, were not considered citizens of the republic and not allowed to vote. In 1959 most of the native Hawaiians boycotted the vote to become a state. In Puerto Rican elections the people were given 3 choices: to stay a commonwealth or territory, become a state, or become independent. The Hawaiians were never given the 3rd choice…

The U.S. military industrial complex has (almost) always had ‘boots on the ground’ under the guise of “liberating” other countries of how they do things and shove our democracy up their bottoms, whether they like it or not. In more recent decades it’s been for their oil, period.

Warmongering Presidents keeping it going and going. For almost a year now, blood thirsty Joe sending endless, completely unaccounted for trillions to Zelensky in Ukraine as he degradingly begs for ever MORE money, thanking the American people for our (forced) ‘generosity’.

Our government has to be making tremendous profits off of all of this, which they’re personally pocketing. It certainly isn’t going to help the people of the U.S. or this nation’s structures as needed, that’s for damn sure. Queen Lili’uokalani had plenty of reason to be furious and upset in the 1890’s!

Was Republic of Hawaii diplomatically recognized?

Yes.

Did US forces play a physical role with overthrow?

No.

1887 consider it clash one.

Lilikulani sought to concentrate all political power in her office. Overthrow.

1894. Weapons from US smuggled to Diamond Head. Wilcox getting hundreds through SanFrancisco Customs.

Defeated. Queen house arrest

Republic formed after. 18 delegates elected. Same voting law as N Y. State at the time. 9 full or part Hawaiian. All voted for Annexation.

Hawaii Republic diplomatically recognized after.

There are inaccuracies in this personal biased truncated story of the events of the Kingdom of Hawaii overthrow coup by the author of this article. The Queen was under physical threat when making the proclamation presented in this article, is just one example.

The claim that there was an annexation and link provided to support said claim is refuted at least in part by the context of the linked text. The annexation vote was patently illegal and the fact of the matter is that there is no legally justified process that makes Hawai’i a part of the USA. It remains an militarily occupied state under international law.