This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

One of the most striking stories over the last week was the expulsion of a pair of African American Democratic legislators from the Tennessee House of Representatives by Republican elected officials. Those two young men, Rep. Justin Jones and Rep. Justin Pearson, along with their colleague Rep. Gloria Johnson, had supported and helped lead the gun control protests undertaken on the House floor by numerous young Tennesseans, demonstrations in response to both the horrific Nashville school shooting and the legislature’s unwillingness to act in the face of such tragedies. After extended, often demeaning public questioning of Jones and Pearson, the House’s Republican majority voted to expel the two of them but not Johnson, a distinction that Johnson herself as well as many others attributed to blatant racism.

The vote to expel these two democratically elected legislators was an unusual and extreme step, and has already been challenged; in the case of Jones it has been reversed. But it does fit within a longstanding tradition of attacking Black legislators, one that helped shape memories of the post-Civil War Reconstruction era for more than a century.

Historians from W.E.B. Du Bois in the 1930s to current figures like David Blight have documented racist images of Black legislators as corrupt, ignorant, and profoundly unsuited for office; these portrayals began to appear almost immediately at the start of Reconstruction. While those images were first created by overt white supremacist domestic terrorist organizations like the nascent Ku Klux Klan, they soon became far more widespread and widely accepted, thanks in large part to the educational textbooks that Du Bois points out in his chapter “The Propaganda of History.” To highlight just one striking example from William Long’s primary school textbook America: A History of Our Country (1923): “Legislatures were often at the mercy of Negroes, childishly ignorant, who sold their votes openly, and whose ‘loyalty’ was gained by allowing them to eat, drink, and clothe themselves at the state’s expense.”

While educational texts disseminated these racist images of Black legislators to schoolchildren, prominent pop culture works likewise did so for an even broader American audience. One of the clearest examples is an extended sequence from D.W. Griffith’s blockbuster silent film The Birth of a Nation (1915). The title card that introduces this sequence not only frames it as “the riot in the Master’s Hall, the negro party in control,” but also claims to present “AN HISTORICAL FASCIMILE of the State House of Representatives of South Carolina as it was in 1870.” The three-minute scene that follows portrays the state’s newly elected Black legislators not only eating, drinking, and cavorting on the House floor, but also quite literally rioting as a violent mob seeking to enact such measures as (per another title card) “a bill providing for the intermarriage of blacks and whites.” This, Margaret Mitchell would write in her blockbuster novel Gone with the Wind (1936), was “Reconstruction in all its implications”: “The negroes are on top,” her heroine Scarlett O’Hara thinks, and “conduct themselves as creatures of small intelligence might naturally be expected to do.”

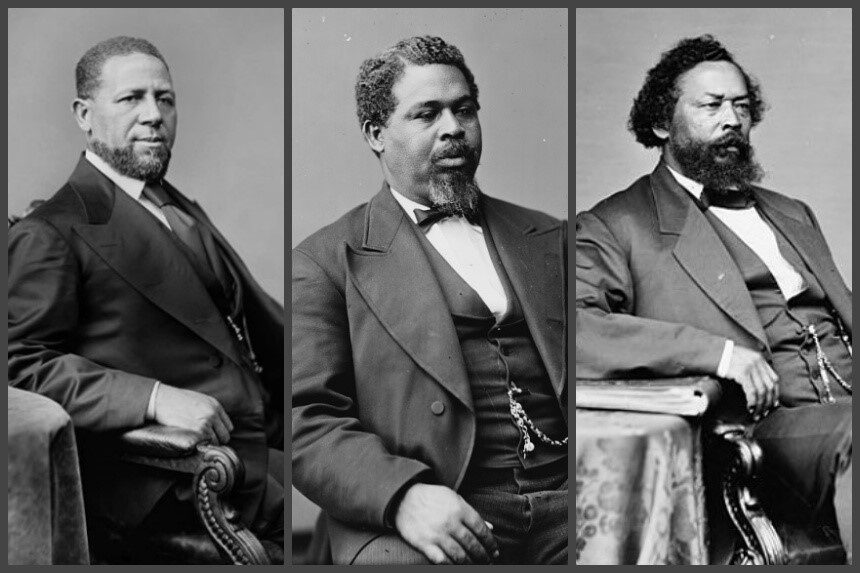

Those are just a snapshot of the propagandistic, mythic, racist images of Black legislators that came to dominate American education, popular culture, and collective memory for much of the century after Reconstruction. The actual stories could not be more distinct, complex, inspiring, and critically patriotic in contrast to those myths. Here are three brief examples from the more than 1500 African American men who held office during Reconstruction:

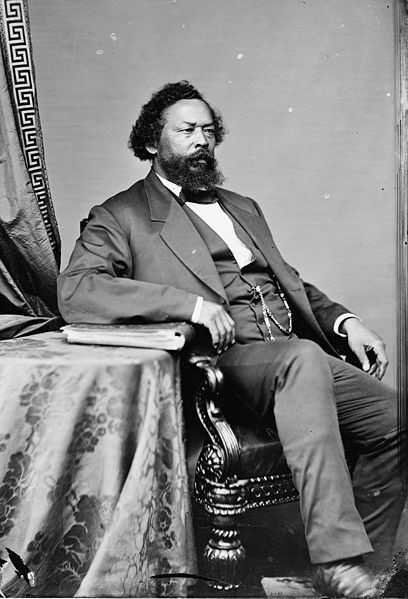

- Benjamin Turner: Born into slavery in 1825 North Carolina, sold down river to Alabama with his mother when he was only five, and freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, Turner became a self-made businessman and farmer in Selma, Alabama while the Civil War was still raging. By 1865, he had enough local clout to found one of the area’s first freedmen’s schools; two years later he attended the state Republican Convention, launching his political career with an appointment as the county’s tax collector. In 1870 he ran successfully for the U.S. House of Representatives; although he only served one term, it was a productive two years, including authoring private pension bills for Civil War veterans and opposing a cotton tax that he saw as disproportionately affecting African Americans. After his 1872 defeat he mostly returned to farming, although he did attend the 1880 Republican National Convention in Chicago — one more reflection of his political and communal role and prominence.

- Hiram Revels: Born in 1827 to free African Americans in Fayetteville, North Carolina, educated for the ministry in Northern seminaries, an itinerant minister for the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church throughout the 1850s, and the chaplain for one of the first African American regiments in the Civil War, Revels’ story differs from Turner’s in just about every way. Yet he too opened one of the earliest freedmen’s schools (this one in St. Louis, where he had been a pastor before the war) and he too became one of the first African Americans in Congress when he was appointed to the Senate by the Mississippi state legislature in January 1870. Like Turner, Revels served only one term (or in his case, only part of one), as he declined a number of appointments after his Senate term ended in March 1871. Yet in that brief time, Revels managed both to fight for the education and rights of freed people and to advocate for universal amnesty for former Confederate soldiers. And in his post-Senate life he continued along both paths, serving as president of Alcorn A&M College (now Alcorn State University) and writing a famous 1875 letter to President Grantdenouncing “carpetbaggers”— a duality that illustrates the breadth of perspectives found among these Reconstruction legislators.

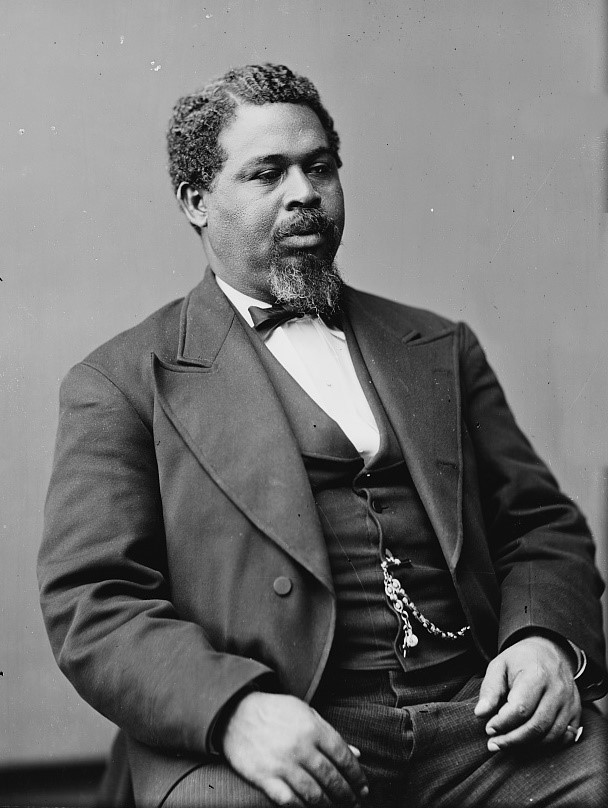

- Robert Smalls: One particular event in Robert Smalls’ amazing life has become well-known in recent years: In May of 1862, the South Carolina maritime pilot commandeered a Confederate ship and sailed it through a Confederate blockade and to the Union lines, where it became a U.S. warship and he became one of the most passionate advocates for African American Civil War service. But Smalls continued his own service during Reconstruction, founding the South Carolina Republican Party, winning election to the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1868, and then winning election to the S. House in 1874 (the start of his five terms in national office). Among his numerous political and social accomplishments, he authored a bill that created in South Carolina the nation’s first free and compulsory public education system, just one example of the enduring legacy of this exemplary Black legislator.

Justin Jones and Justin Pearson can speak for themselves in our own moment, and have done so with amazing power before, during, and after their expulsion from the Tennessee House. But they are also part of a longstanding and inspiring legacy of Black legislators in America, one that starts ironically in the same era in which the racist images of Black legislators originated.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

What happened in Tennessee was blown out of proportion by the local media, social media, and mainstream media.

What those legislators did was to use the floor of the House Chamber as a means to try and incite a riot using a bullhorn and speeches intended to stir up the crowd outside the chamber. It did not follow any sort of established order set forth by the Tennessee State Constitution and recognized by the Speaker of the House. The legislature had every right and duty to expel all three troublemakers whose actions prove they really are unfit to serve and represent citizens in their respective districts. Unfortunately, one of those troublemakers, Gloria Johnson survived the Expulsion Vote thus making it a “Racial” Issue which it really wasn’t. It’s troubling the local and mainstream media took it upon themselves to turn it into one. I am a citizen of the State of Tennessee. I am familiar with the State Constitution. I am not a member of the State House of Senate. But, knowing my history and the state constitution, I fully agree with and uphold the expulsions. They deserved it. There just should have been a third one for Ms. Johnson.

Once again, Professor Ben Railton has used history to give us insight into today’s news.

How terrible that any American — whether living today or in the past — could stereotype Blacks with such prejudice.

And how proud we all should be that Americans, Black and white, have fought that bigotry by living the truth that all of us are created equal.

Thank you, Professor Railton!