This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

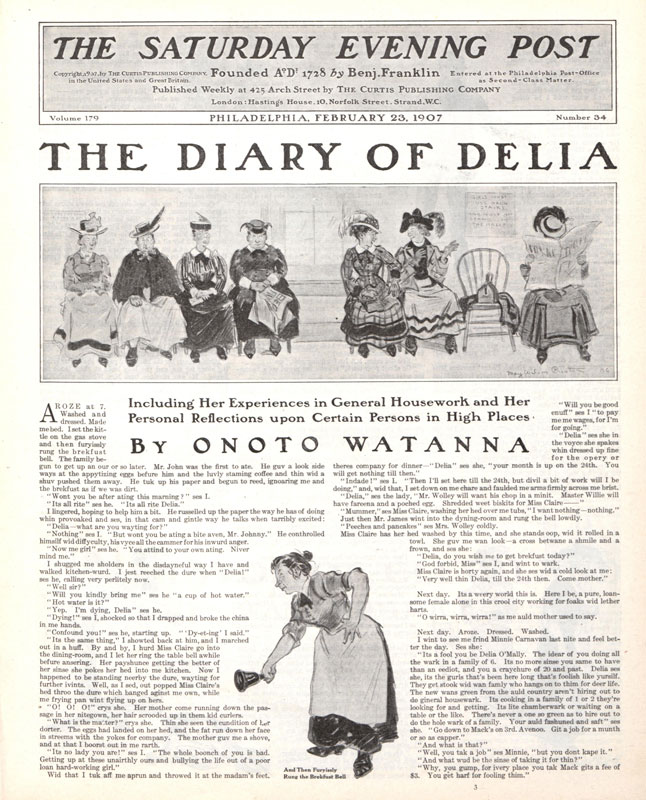

As we begin this year’s celebration of Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month, and as the members of the Writer’s Guild of America (WGA) continue their recently launched strike for fairer compensation and treatment in the entertainment industry, there’s no more compelling story to commemorate than that of the first Asian American screenwriter, Onoto Watanna.

Watanna was the pseudonym of Winnifred Eaton (1875-1954), one of twelve children of English merchant Edward Eaton and Chinese acrobat and performer Achuen “Grace” Amoy. (She also happens to be the younger sister of Sui Sin Far, the first American writer of Asian descent to publish fiction in English and the subject of my first Considering History column.)

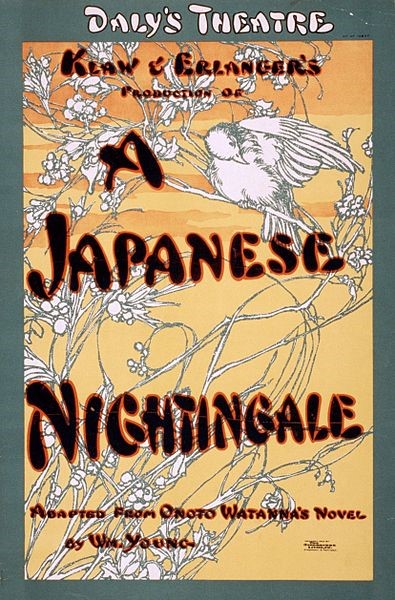

In the five years after publishing her first romance novel, 1899’s Miss Nume of Japan, when she was not yet 24 years old, Watanna wrote and published five more books (while still contributing numerous stories to magazines as well), a stunningly productive start to a literary career. Of those six early books, the most influential in both her own career and American culture was her second, A Japanese Nightingale (1901), which became a bestseller and was adapted into both a 1903 Broadway play and a 1918 silent film. While Nightingale’s story of a beautiful and endangered geisha certainly echoed stereotypical ideas about Japanese culture and women that helped it gain those wide audiences, Watanna’s beautiful prose and nuanced characterizations helped ensure that her readers came away from the novel both moved and changed in any such prejudices.

In 1914-15, Watanna published two important books that took her career to significant new places. Her 1915 novel Me: a Book of Remembrance, serialized in two parts in the popular Century Illustrated magazine, was as profoundly autobiographical as its title suggests, so much so that Watanna originally published it anonymously before claiming authorship. It was also a passion project for Watanna; she composed the novel in a period of just two weeks after undergoing a hospitalization. Her friend and fellow writer Jean Webster called it “one of the most astounding literary feats I have ever known.”

Watanna’s sister Sui Sin Far wrote movingly about her childhood and multiracial heritage in the essay “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian” (1909); Watanna does so just as potently and at far greater length in Me, opening with a scene of her leaving home at the age of seventeen and leading readers across every part of her life and career before, during, and since that turning point moment.

Perhaps the impulse to revisit her childhood and family had arisen from the other important book Watanna published in this period: 1914’s Chinese-Japanese Cookbook. Co-written with another of her older sisters, Sara Eaton Bosse, this cookbook acknowledged the evolving popularity of Chinese and Japanese restaurants in the early 20th century United States and advanced a bold goal in response: “There is no reason why these same dishes should not be cooked and served in any American home.”

Amidst the ongoing discriminations of the Chinese Exclusion Act era, and with the more recent “Gentleman’s Agreement” having extended the exclusions to Japanese arrivals, Watanna and Bosse’s cookbook wasn’t simply a culinary innovation: it represented an inspiring attempt to use food to change the prejudices behind such policies. “The Westerner” who cooks these dishes, they write, “will cease to feel that natural repugnance which assails one when about to taste a strange dish of a new and strange land.”

Not long after the cookbook’s publication, inspired in part by the silent film adaptation of Nightingale, Watanna began to write “scenarios,” treatments for potential films. Much of that early screenwriting work went uncredited and was apparently poorly compensated at best, treatment about which Watanna wrote passionately in her 1928 Motion Picture Magazine article “Butchering Brains: An Author in Hollywood Is as a Lamb in an Abattoir.” If Watanna’s sole contribution to Hollywood were this article, it would be more than enough to justify better remembering her as part of film and entertainment history; she notes in her opening that not all authors who experience such mistreatment “go silently,” that “many fare forth shooting verbal fireworks behind them.” Few have ever shot off such fireworks more eloquently than Watanna does here.

But Watanna’s dedication and talent meant that even this frustrating reception did not keep her from making her own mark on early Hollywood history. Indeed, five of her six credited screenplays, all for Universal Studios, were produced in the two years after that article’s publication. Many of them brought together Watanna’s enduring interests in both romance stories and Asian American histories, as illustrated by films like Shanghai Lady (1929) and East Is West (1930). The latter film particularly reflects the complicated cross-cultural currents of early Hollywood, with Lupe Veléz (a groundbreaking Mexican American actress known as “the Mexican Spitfire”) playing Watanna’s Chinese American heroine Ming Toy, a woman torn between Edward G. Robinson’s “Chop Suey King” gangster villain Charlie Yong and the film’s romantic hero Billy Benson (played by All Quiet on the Western Front’s Lew Ayres).

Shortly after East Is West’s premiere Watanna left Hollywood for Alberta, where she spent the remaining quarter-century of her life active in the province’s pioneering Little Theatre Movement and served as president of the Canadian Authors’ Association. It was her one final stage in an inspiringly multilayered life and career, a perfect story to commemorate for this year’s Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now