One of the first big controversies of the 1960s was birth control. Americans were sharply divided over the morality of “the pill.”

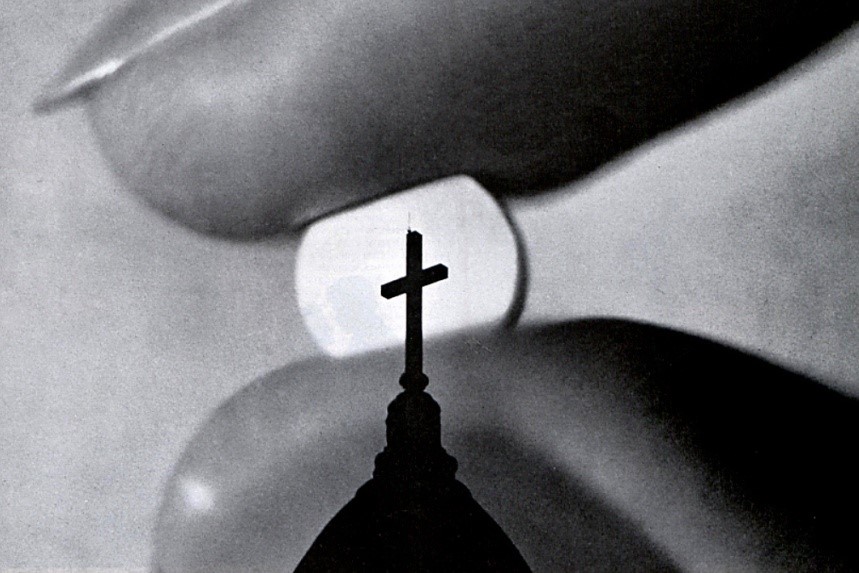

On April 20, 1963, The Saturday Evening Post presented “It Is Time to End the Birth Control Fight,” written by Dr. John Rock, a highly respected specialist in gynecology.

Rock had directed the first clinical trials of the progesterone contraceptive. He had the scientific background to speak knowledgably about the subject. He was also a devout Catholic, which enabled him to address the spiritual objections of birth control pills’ strongest opponent. In the editorial he advocated for a public policy of toleration, and wrote that “…all restrictions on birth control, written or unwritten, should be removed.”

But his editorial was not the last word on birth control. And it was far from the first.

In 1878, a federal law banned obscene literature from the mail. Contraceptives or information about birth control were included in the ban. The original sponsor of the bill, Anthony Comstock, wondered why birth control was even necessary. He asked, “Can’t everybody, rich or poor, learn to control themselves?”

Twenty-four states passed laws similar to the federal “Comstock Law” with comparable obscenity bans to make contraception illegal. These laws were based on the belief that divorcing sex from its possible consequence might encourage immoral behavior. Birth control would encourage adultery.

But proponents of birth control, like Margaret Sanger, argued that it could give women relief from continual child-bearing. It would let them determine the appropriate number of children for their circumstances. There was also the concern that a rapidly expanding population could soon exhaust earth’s resources.

By the 1920s, the repressive Victorian spirit had lost much of its influence. More women were asking their physicians for help in regulating family growth. But physicians were still forbidden by state laws from providing or counseling patients on contraceptives.

This changed in 1936, when a doctor was found guilty of ordering contraceptives from Japan. When the case was referred to a Federal Appeals Court, a judge noted that the original wording of the Comstock Law made an exception for contraceptives that were prescribed by “a physician in good standing, given in good faith.” The words had been removed in the final version of the bill. The judge restored doctors’ right to prescribe and advise on birth control.

However, state laws still outlawed contraception itself. It was a principle that was losing favor with the public. A 1943 poll by Fortune magazine found nearly 85 percent of women nationwide believed all married women should have access to birth control.

In the 1950s, Sanger — still working to legalize birth control — spoke to a researcher who believed a human hormone, progesterone, could be used to prevent ovulation and conception. The researcher, Dr. Gregory Pincus, worked with Post contributor Dr. Rock to conduct clinical trials of his anti-ovulant pill, first with a small group in Massachusetts, then on a large scale trial in Puerto Rico.

The 1956 trials proved that the progesterone pill was a safe, reliable, and convenient contraceptive. The following year, the FDA approved its use, not for contraception but for reducing discomfort in menstruation. Hearing this, many American women began reporting severe menstrual problems to their physicians. By the end of 1959, over half a million women were taking Searle’s formulation of the pill, brand-named Enovid.

By 1960, The Food and Drug Administration had reviewed field trials of almost 900 women who had taken the pill. It gave G. D. Searle approval Enovid as a contraceptive.

But the ban on contraceptives remained in many states. And the Catholic church would not condone the use of it or any other contraceptive.

In his 1963 Post article, Dr. Rock pointed out that birth control could be a positive response to the impending population crisis. “Some 800,000 years were required for humanity to achieve a current population of three billion,” he wrote. “But at current growth rates, the second three billion will be added in the next 40 years.”

Addressing ecclesiastical opposition, he argued that family planning was a part of the responsible parenting that was important to the Catholic faith. Further, the pill didn’t violate the church’s teaching that reproduction should never be suppressed. The pill didn’t change a bodily function but simply modified its sequence. The church’s final word on the pill would now await the recommendation of the Vatican’s “Birth Control Commission.”

Meanwhile, several states still prohibited contraceptives. Connecticut’s laws were particularly harsh; married couples could be arrested for using birth control in the privacy of their own bedrooms and subjected to 60 days in jail.

The law had been challenged in 1940, but the Connecticut Supreme Court upheld the law, saying the General Assembly had the right to legislate such matters on behalf of the public health and morals.

In 1961, Dr. C. Lee Buxton, of Yale Medical School’s ob/gyn department, and Estelle Griswold, of Connecticut Planned Parenthood, challenged the Connecticut law by opening a birth control clinic. They were promptly arrested and convicted of violating state law. They appealed the case to the Supreme Court.

The state of Connecticut argued that its legislature had a right to pass laws that would “reduce the chances of immorality” and deter sexual intercourse outside of marriage. The state added that married couples were still able to practice birth control by the periodic-abstinence method endorsed by the Catholic church.

In 1965, the Supreme Court struck down the state law. The justices didn’t enter into a debate of the consequences of birth control but asserted an overriding constitutional right: the right to privacy. It was a right, the justices said, inherent in the First, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments.

Justice William O. Douglas asked if the state was really ready for its police “to search the sacred precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of contraceptives?” The idea, he concluded “was repulsive to the notion of privacy surrounding the marriage relationship.”

Two years later, the right of privacy was extended to include unmarried couples in Eisenstadt v. Baird.

In 1967, Vatican’s Birth Control Commission looked like it would be agreeable to allowing birth control; after hearing testimony from married women, they voted to remove the ban on oral contraceptives. However, Pope Paul VI overruled its recommendation and pronounced that the ban should remain on all birth control methods save one: periodic continence, familiarly known as the rhythm method.

Today, the Vatican still objects to any form of contraception, but it gets little support from American Catholics. A 2016 Pew Research Study found only 13 percent agree that contraceptive use was morally wrong. And a study by the National Survey of Family Growth found 92 percent of American Catholics had used some form of contraceptive.

Americans in general seem to have few reservations about birth control. Of all women between 15 and 49, 65 percent are using some form of contraception, according to a 2018 report from the Centers for Disease Control. The most frequently used form is tubal ligation (also termed female sterilization) at 19 percent, oral contraceptives (13 percent), intra-uterine devices (11 percent), and male condoms (9 percent).

Americans’ acceptance of birth control has steadily grown; between 1965 and 1983 the percentage who believed birth control information should be available to all women grew from 73 percent to 90 percent.

But that doesn’t mean it’s free from controversy; today, clashes over some forms of birth control are happening at the state level. How these laws play out will depend on elected legislators and the people who vote for them.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now