Country music star Jason Aldean’s latest song, “Try That in a Small Town,” has stirred up a great deal of controversy. The lyrics to the song highlight a number of things that the audience should not try in said small town setting, from overt criminal behavior to stomping on or burning the flag to confiscating guns. More troubling is the chorus’s implication that if one does try those things, one will meet with vigilante mob justice: “Well, try that in a small town/See how far ya make it down the road/Around here, we take care of our own/You cross that line, it won’t take long.” Adding fuel to the fire was the music video, which features Aldean performing on the steps of a Columbia, Tennessee courthouse that was the site of a prominent 1927 lynching. Country Music Television has pulled the video out of rotation, without comment.

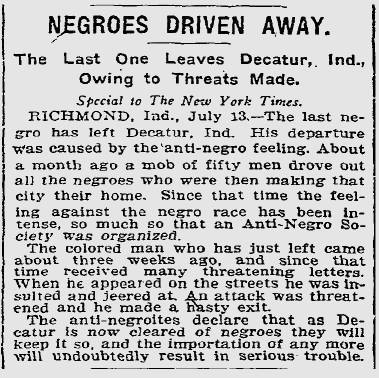

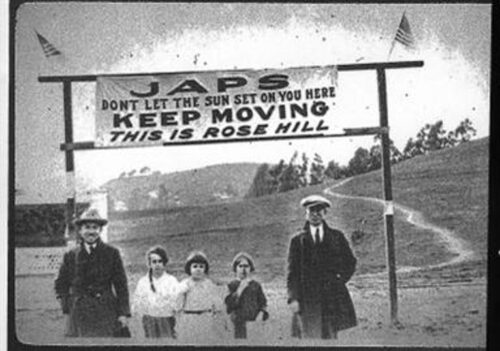

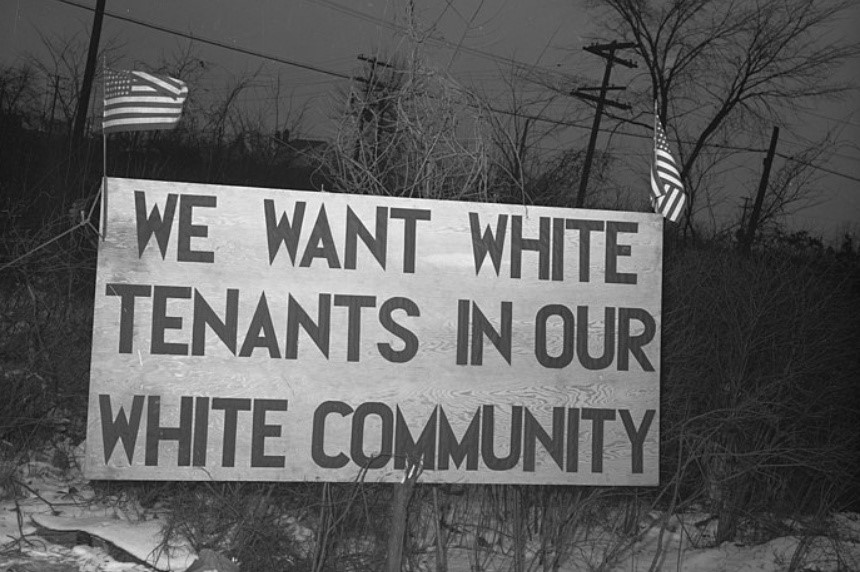

Aldean’s song makes no overt reference to either lynching or race. But even without those explicit details, the song’s concept of communities where certain behaviors — and, by clear implication, certain individuals — will be met with mob violence echoes a once-common yet largely forgotten setting in American history: the sundown town. They were given that name due to the phrase “Don’t let the sun set on you here,” a concept sometimes captured blatantly in signs at the town line but often signaled in other, equally troubling ways. These exclusionary and violent towns were found around the country through much of the 20th century and targeted multiple communities of color.

No work on sundown towns can fail to mention the scholar most responsible for unearthing and sharing these histories, James Loewen. Loewen turned his book Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism (2005) into a groundbreaking and evolving web project, and since his 2021 passing, his home institution of Tougaloo College has continued to maintain and update that website. The site’s centerpiece is a map that serves as a database through which users can learn about the many sundown towns (some ambiguous due precisely to these histories’ hidden quality, but many quite clear) that Loewen and his team identified in every state, and to which everyone can contribute further information about these and other possible sundown towns.

Some of those sundown towns are places we might expect, due to their history as well as more current events. One such community is Ferguson, Missouri, the St. Louis suburb that, thanks to redlining practices and more overt forms of discrimination and threats, became almost entirely white between 1940 and 1960. In recent decades the demographics have shifted dramatically, and Ferguson is now a minority-majority community. But its sundown town era is of course inseparable from both the long history of slavery in Missouri and the contemporary issues of racial profiling and police brutality that have brought Ferguson to national prominence over the last decade.

Other sundown towns identified in the database are more surprising, however. One of the 17 Massachusetts communities listed there is Groton, a small town in northeastern Massachusetts (not far from the New Hampshire border) that the database identifies as “the stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan in the Nashoba Valley.” In the course of the 1920s the Klan became so powerful in town that it took over events like the Groton Fair and forced and kept out most residents of color; although the Klan’s power waned during the Depression, Groton has remained almost entirely white for the rest of the century and into the present.

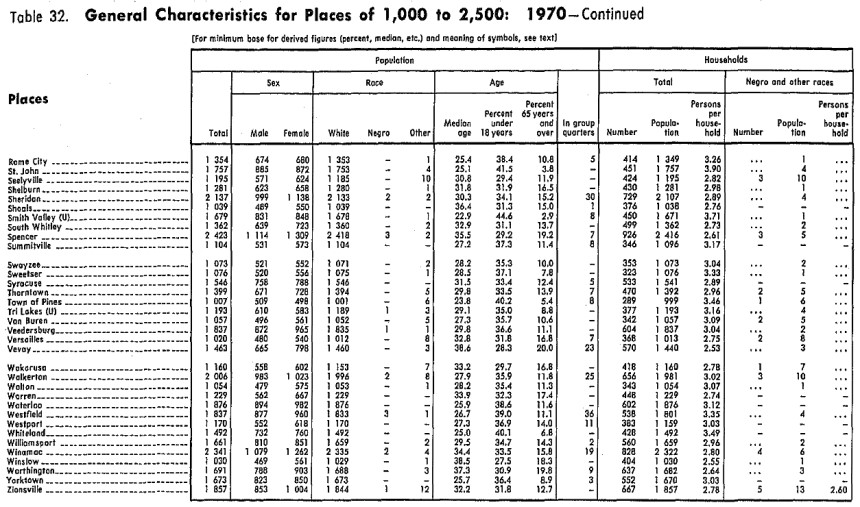

Table from the 1970 U.S. Census showing the race of residents in Indiana towns between 1,000 and 2,500 people. (U.S. Census). Tougaloo College notes that the table shows how widespread all-white towns were in Indiana.While most sundown towns were, as the name suggests, individual communities, at least two entire American states operated in this racially exclusionary way. In 1844, the same year that it banned slavery from the territory, Oregon passed the Black Exclusionary Law, making it illegal for African Americans to enter (much less remain in) Oregon Territory; those found in the territory were subject first to whippings under the “Peter Burnett Lash Law” (named for the judge who drafted it) and later to forced labor. After Oregon became a state in 1859 these exclusionary laws remained on the books, and indeed were not repealed until 1926. Meanwhile, in 1853 Illinois passed its own, even more extreme such Black Law. This version not only levied a heavy fine on any African American found in the state, but also authorized sheriffs to capture and sell to the highest bidder (basically enslave by another name) any person who could not pay the fine.

Table from the 1970 U.S. Census showing the race of residents in Indiana towns between 1,000 and 2,500 people. (U.S. Census). Tougaloo College notes that the table shows how widespread all-white towns were in Indiana.While most sundown towns were, as the name suggests, individual communities, at least two entire American states operated in this racially exclusionary way. In 1844, the same year that it banned slavery from the territory, Oregon passed the Black Exclusionary Law, making it illegal for African Americans to enter (much less remain in) Oregon Territory; those found in the territory were subject first to whippings under the “Peter Burnett Lash Law” (named for the judge who drafted it) and later to forced labor. After Oregon became a state in 1859 these exclusionary laws remained on the books, and indeed were not repealed until 1926. Meanwhile, in 1853 Illinois passed its own, even more extreme such Black Law. This version not only levied a heavy fine on any African American found in the state, but also authorized sheriffs to capture and sell to the highest bidder (basically enslave by another name) any person who could not pay the fine.

African Americans were far from the only community of color targeted by sundown town practices and policies. Two Nevada towns, Minden and Gardnerville, were particularly infamous for their exclusionary discrimination and threats toward Native Americans. From 1917 to 1974 an ordinance in both towns required Native Americans to leave by 6:30 p.m., and a whistle (later a siren) sounded at 6 p.m. to warn them of this impending deadline. Minden continues to play its “sundown siren” to this day despite protests. Numerous towns featured similar warnings and threats toward Asian American communities, with Antioch, California a striking example: this Bay Area town banned Chinese Americans from being outside after sunset as early as 1851, and its small Chinatown neighborhood was burned to the ground in an 1876 white supremacist riot. The effects of those exclusions were still obvious as late as the 1960 census, in which only 12 of the town’s 17,000 residents were Chinese American.

These still largely hidden sundown town histories don’t simply reveal details of their particular communities — they are also inseparable from broader shared stories. One telling example is the 1986 sports film Hoosiers, the inspiring story of fictional Hickory High School and its improbable road to an Indiana state basketball championship (based loosely on Milan High’s 1954 season). As Loewen writes in Sundown Towns, however, “One Indiana resident relates, ‘All southern Hoosiers laughed at the movie called Hoosiers because the movie depicts blacks playing basketball and sitting in the stands at games in Jasper. We all agreed no blacks were permitted until probably the ’60s and do not feel welcome today.’ A cheerleader for interracial Evansville high school tells of having rocks thrown at their school bus as they sped out of Jasper after a basketball game in about 1975, more than 20 years after the events depicted so inaccurately in Hoosiers.”

It’s likely that neither Jason Aldean nor most of his defenders are aware of these histories, despite their echoes in his song and video alike. But that’s precisely the point: until we collectively understand the history of sundown towns and what they reveal about American racism and exclusion, we can’t begin to deal with their legacies in our own time.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

For Stephen, if you are aware of any sundown towns that barred white people based on class/socioeconomic status, identify them and stop complaining. They don’t exist. You would have identified them in your comment. Your argument is non-sensical due to the fact that race and class are not one and the same.

This article is just another piece of liberal, left-slated b******t by the Saturday Evening Post Snowflakes. Keep your political opinions out of your articles and to yourselves. You’d be better off and wouldn’t turn off your conservative segment of readers in the process.

I was born in a small town. I was raised in the rural area outside the small town. I live in a rural, sparsely populated area today about ten miles from the nearest town, also small. I would not dream of anywhere else. I don’t follow Country Music but I am right on with Jason Aldean’s “Try that in a Small Town.” I know exactly what would happen to anyone pulling the crap he mentions in rural sections of Tennessee. Some violators might “disappear.” We know how to take care of ourselves in small towns and rural areas and we strongly believe in, support, and practice what is guaranteed by the Second Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America. May God Always Bless and Keep Small Town and Rural America Safe.

This article has, either intentionally or unintentionally, forgotten to mention there were Sundown Towns in some states (Oklahoma) where, if you were white, YOU better not be found in after sundown. This nation has been very unjust to just about everyone, but it seems only one race ever gets mentioned more than a sentence.