Over the last couple weeks, American political and cultural debates have turned to an unexpected but appropriately summery subject: public swimming pools. A CNN Business story noted that the small number of public pools in 2023 America makes it more difficult for folks to navigate profound heat waves. New York Times op-ed columnist Mara Gay helped further the debate with a column arguing that the striking number of drowning deaths in recent years is related to that decrease in public pools and their readily available swimming lessons. But conservative commentators like Erick Erickson have pushed back, criticizing these calls for more public pools as nothing more than another government “entitlement program.”

The emphasis on current events and political policies are understandable and perhaps even inevitable. But everything has a history, and the public swimming pool is a space that is deeply rooted in American history across multiple time periods. The public pool’s evolution throughout the 20th century and into the 21st reflects some of our most longstanding and frustrating national divisions, a painful shared past with which we must grapple if we’re to argue for more public pools in the present.

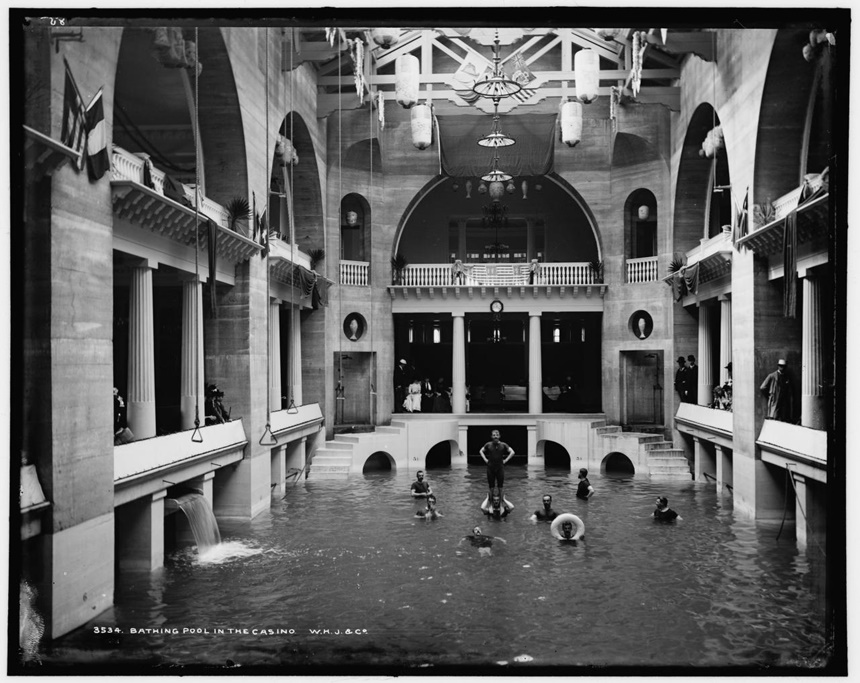

The first wave of public pool construction in the United States occurred in the late 19th century, but these pools were intended more for bathing than for swimming. While the period’s wealthier Americans had indoor plumbing and thus access to their own baths, many working-class and poorer Americans could not afford those luxuries, and so public pools became a space for bathing at the end of the workday. Those pools were generally segregated by gender, as the emphasis on bathing combined with the evolution of bathing suits (even in their significantly more modest early form) led to a sense of intimacy in this space.

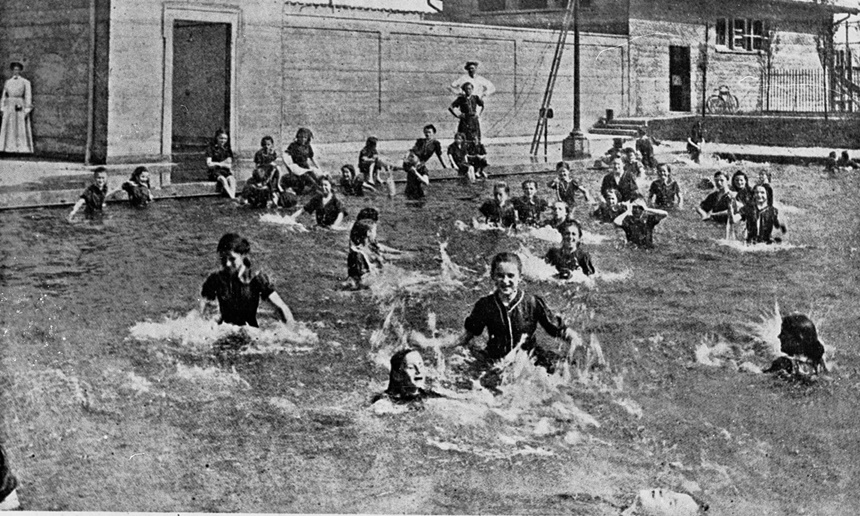

The greater understanding of germs and other public health issues at the turn of the 20th century led to a move away from pools and toward more regulated and sanitary bathhouses as sites of public bathing. But while this development did decrease the number of public pools somewhat, it contributed more to a shift in the pool’s purpose, toward a new emphasis on swimming and leisure. Chicago’s Douglass Park Pool was a famous early example of these more recreational public pools, and soon every city had its own equivalents. Moreover, during the 1930s both renovating old pools and building new ones became popular projects for the New Deal’s Civil Works Administration (CWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA), with federal workers building over 800 new pools and repairing over 300 existing ones in the course of these Depression-era projects.

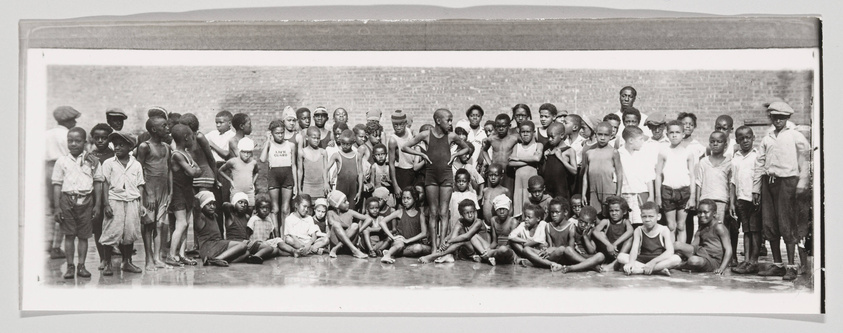

Unlike their bathing predecessors, these recreational public pools were not usually segregated by gender. The newly mixed-gender pools tapped into longstanding racist fears of threatening and sexually violent Black men, white supremacist prejudices which, amplified by the movement of large numbers of African Americans to cities across the country as part of the Great Migration, led to ubiquitous racial segregation in these 1930s and ’40s public swimming pools. As swimming pool historian Jeff Wiltse notes, that segregation created hugely disparate opportunities for white and Black pool-goers, as illustrated by St. Louis: while African Americans comprised 15 percent of the city’s population in the 1930s, they had access to just one public pool, while white residents had nine pools. As a result, Black residents took only 1.5 percent of the public swims during that period.

As with every form of racial segregation in American history, this swimming pool segregation was enforced and reinforced by violence. Wiltse highlights two such violent events in 1930s Pittsburgh: opening day of the Highland Park Pool in 1931, when Black swimmers were attacked by a mob of white swimmers; and the July 1935 beating of Black 9-year-old Frank Reynolds at Paulson Pool, after which a police officer told Reynolds’ mother, “Why can’t you people use the Washington Boulevard pool? I don’t approve of colored and white people swimming together.” By far the most extreme of these violent events took place at St. Louis’s Fairground Pool Park on the day of its June 1949 reopening as an integrated pool; this Fairground Park riot continued throughout the day and into the subsequent night, and saw Black swimmers and passers-by alike attacked by roving white mobs.

That riot achieved its white supremacist goals, as St. Louis resegregated its public pools for many years. Shortly thereafter, such racial segregation was ruled illegal, however; in the wake of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision and the subsequent Civil Rights Act of 1964, the desegregation of public pools became a widely shared goal. Yet rather than take part in that process, many cities and communities engaged in acts of massive resistance, choosing to defund and close public pools. Unfortunately, they did so with the support of the Supreme Court: in the 1971 Palmer v. Thompson decision, the Court ruled that the city of Jackson, Mississippi, which had closed four of its five public pools and transferred the fifth to a whites-only YMCA, had done so legally as long as the action did “equal damage” to every resident.

The closure of public pools most certainly did not do equal damage, however, and not only because only white swimmers could use a segregated pool like the YMCA’s. Beginning in the 1960s and ’70s, a boom in private home pools and those located at exclusive country clubs made swimming pools a space largely accessible to wealthier and whiter Americans, at the expense of the diverse communities that public pools could feature. This trend coincided with the larger history of white flight that so thoroughly transformed America’s cities in the second half of the 20th century. And the ongoing shift in swimming pools from urban to suburban, from public to private, doesn’t just mean that pools have become a space localized in particular American communities; it also and more destructively means that many communities have no access to public pools at all.

I grew up across the street from a private swimming pool that remained racially segregated long after it was legally possible to do so, and yet I first learned to swim from a beloved Black public school employee at a public pool, so I find echoes of these histories across much of my own life, as do many Americans.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Seems like a lot of community pools are dwindling away due to the rising cost of insurance or lack of labour to operate. For the first time I can remember the Smithville (TN) Municipal Pool did not open for the season and is remaining closed due to the lack of ample labour to maintain. No one wants to work when they figure they can stay home and get paid. That’s Bidenomics for you!

On another note after seeing those pictures of large public pools in the past, there was one at Lake Winnie Amusement Park near the Tn-GA State Lines for years until it was closed in the late 1950s or early 1960s due to the number of drowning deaths at the pool. Nowadays, the Haunted House Ride sits atop of where the pool once was.