When entering the Transatlantic Slave Trade exhibit, the walkways are narrow, the lights dimmed, and visitors can hear waves crashing and chains clinking, which evokes the sense of being cramped and confined in the dark hull of a ship during the Middle Passage. As the descendant of enslaved people, I felt overwhelmed by this space at first. I felt the pressing need to rush through the exhibit to exit the seemingly tight space. But I took a few deep breaths, steadied myself, and continued to take it all in. As a student of African-American history, I know the stories of my ancestors, but I had never seen so many artifacts of our centuries of enslavement in one place. The rusted wrought-iron ankle shackles will forever be etched into my memory. As I looked upon them, I realized that my existence is proof of my ancestors’ resilience.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture sits on a five-acre plot of land near the Washington Monument. Wrapped in ornamental bronze-colored metal lattice and inspired by the three-tiered crowns used in West African art, the building’s striking façade stands in sharp contrast to the stone and marble buildings and monuments that surround it. Since the doors opened in 2016, the museum has welcomed 10 million in-person visitors and millions more through its digital presence.

One comes here for a history lesson taught through the prism of the African-American experience. What you’ll also find is a powerful testament to African-American creativity, tenacity, and resilience. It’s a beacon of hope and remembrance. Museums help “people recognize how much we share, despite our differences, and how much those differences can help us grow,” writes Lonnie G. Bunch III, the NMAAHC’s founding director and Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

The museum’s 105,000 square feet of exhibition space is organized into three sections — history, culture, and community — spread over five floors of galleries, three below ground and two above, with public spaces in between. With more than 40,000 artifacts in its care, the NMAAHC tells the story of the African-American experience with accuracy, honesty, and respect.

Exhibits on the lower three levels focus on the history, from slavery through the civil rights marches and beyond. Aboveground, galleries celebrate the contributions African Americans have made to the country and the world. As you rise through the various floors, both the subject of the exhibits and the physical space get lighter, transitioning from the darkest chapters of history to upper floors devoted to cultural, artistic, scientific, political, and athletic accomplishments.

Museum staff suggest that the best way to experience the museum is from the bottom up, starting with the history section, where exhibits are arranged chronologically.

To access the history galleries, visitors take a glass-enclosed elevator on the main floor. The elevator serves as a time machine, transporting passengers 70 feet underground and centuries back in time. As the elevator descends, you watch the years on elevator shaft walls go by as well. When you step off the elevator, you step into the Slavery and Freedom exhibition, which begins in 15th-century Africa and Europe with the transatlantic slave trade and goes all the way through the 1870s and Reconstruction in the United States.

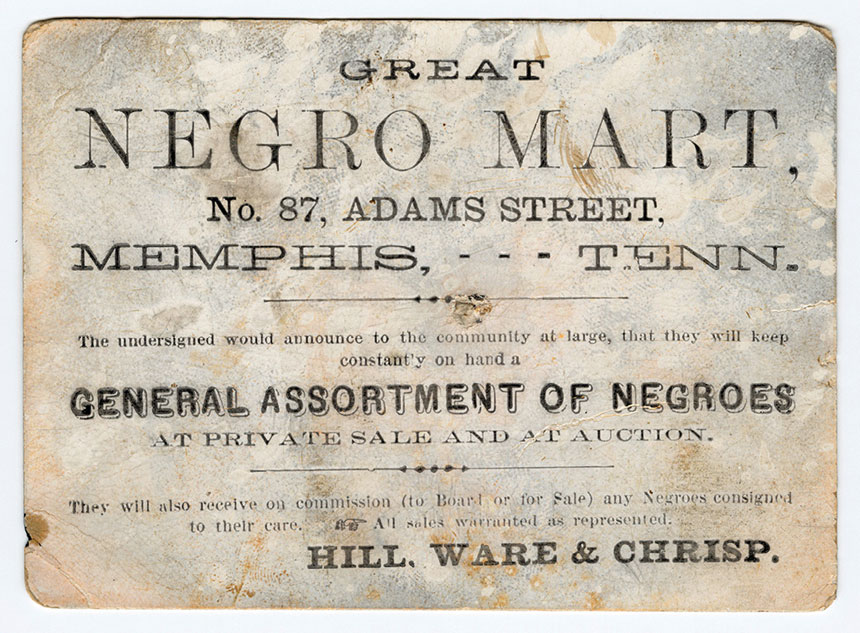

Further in the museum, you discover a stone auction block and a bill of sale for a 16-year-old enslaved girl who was bought for $600. In the background, recordings of enslaved people play in a loop, evoking the trauma of being regarded as chattel to be auctioned off and separated from their families. Nearby, a life-size statue of Thomas Jefferson, who called slavery an “abominable crime,” stands beneath his indelible quote from the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal.” Behind him are stacked more than 600 bricks, each one bearing the name of one of the enslaved people he owned during his lifetime. Other artifacts displayed in the exhibit include Nat Turner’s Bible, a shawl that belonged to Harriet Tubman, and sets of tiny shackles designed to fit around a child’s ankles.

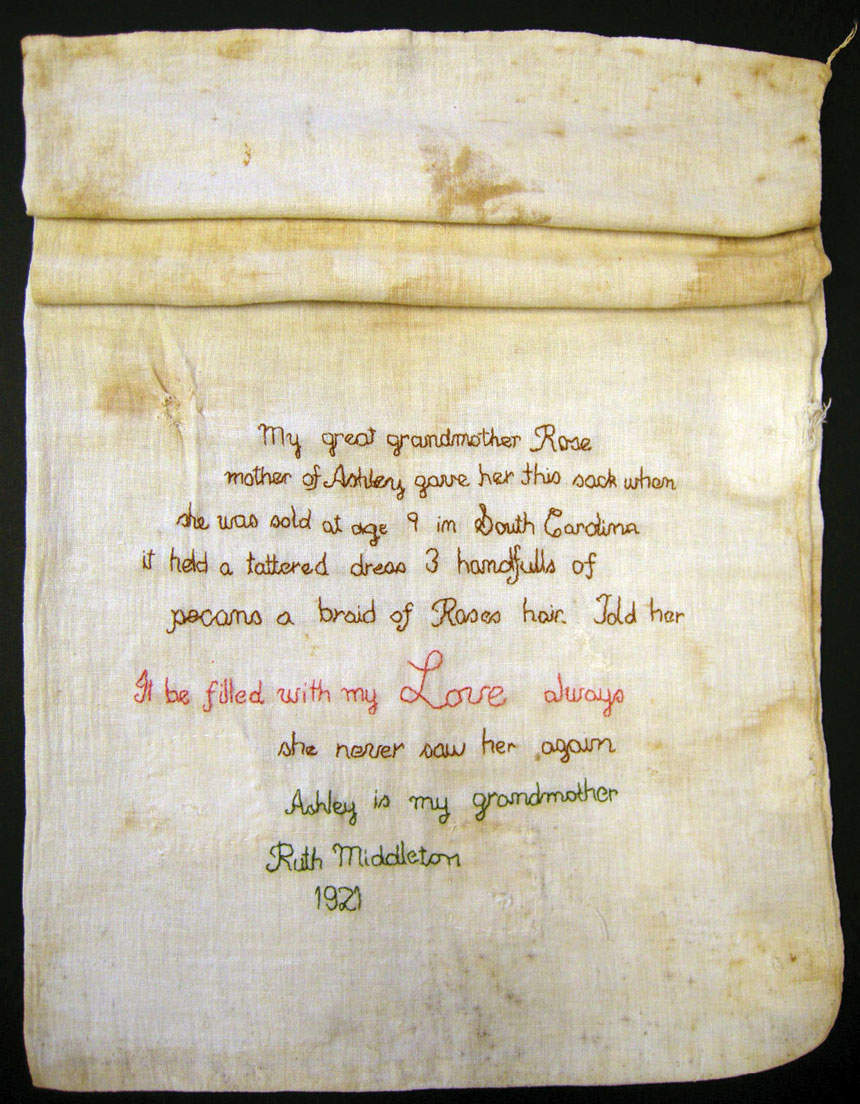

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

She never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

(Courtesy Middleton Place; NMAAHC)

I was particularly captivated by a small piece of embroidered cloth titled “Ashley’s Sack.” A placard states that it had been given to a nine-year-old enslaved girl by her mother as she was being sold away from her family. It was later embroidered in 1921 by Ashley’s great-granddaughter with words explaining the history of the item. The stitched words were sweet and simple, but I was struck by how much love was reflected in the act of preserving this memento across the generations amid so much suffering.

You walk up the ramp to the second level, where exhibits delve into the period following the Reconstruction, during which the country grappled with what rights the newly freed should have. You move through distinct periods, from the Jim Crow era to the beginnings of the modern Civil Rights movement. Here is Rosa Parks’ dress, a segregated railcar, stools from the famous sit-in at the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth’s, and shards of glass from the 1962 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church.

Moving forward in time to level C1, an exhibit titled “A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond” explores contemporary Black life and touches on the events that galvanized the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. When entering this section, visitors are greeted with the iconic photograph of Black Panther Huey Newton sitting in that high-backed wicker chair, while James Brown’s “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” blares over the speakers. The history lesson continues in this section, from the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., through the birth of hip-hop, and on to the election of President Barack Obama.

One might ask, why now? Why build such a museum in the 21st century? Actually, the idea for the museum spools back to 1915 when a group of Black Civil War veterans formed a committee to build a memorial to African-American achievement. Although the measure received some support from President Hoover in 1929, Congress failed to fund the project. More than 70 years later, in 2003, the museum was established by an act of Congress. To bolster the museum’s historical holdings, organizers in 2008 launched the Saving African-American Treasures campaign, which encouraged ordinary people to donate historical items and family heirlooms. By opening day in 2016, organizers had amassed more than 36,000 artifacts, with approximately 3,500 on display.

segregated South. (Photo by Alan Karchmer/NMAAHC)

After an emotional journey through the historic portion of the museum, it’s time for a pause on the concourse level in Contemplative Court, where a cylindrical fountain gently rains into a pool. The sound of the waterfall has a calming effect. Along the walls are quotes by notable African Americans.

In the Culture and Community galleries on the third and fourth levels, exhibits are organized by subject rather than by date. It’s an eclectic mix of African-American art, music, the military, and sporting achievements. Items on display include a pair of Muhammad Ali’s boxing gloves, Halle Berry’s Academy Award, and Chuck Berry’s cherry red El Dorado.

I am particularly drawn to a section called “Making a Way Out of No Way,” which features the creative ways African-Americans cultivated and served their communities through education, businesses, religious institutions, and voluntary organizations. Particularly touching is a replica of the Hope Rosenwald School in Pomaria, South Carolina, which served Black children in the rural South. Nearby is “Double Victory: The African American Military Experience,” with attention to the dual struggle faced by African Americans during World War II — a fight not only against fascism abroad but also discrimination at home. The exhibit also spotlights the wartime contributions of African-American women.

You come to an exhibit devoted to “Afrofuturism,” which is a movement in art, music, and literature that explores the intersection of the African diaspora culture with science and technology. A white tube-like structure illuminated in blue light lines one wall. Entering it, you feel as though you’re boarding a spaceship. Inside are a variety of objects, ranging from Octavia Butler’s typewriter to Nichelle Nichols’s Star Trek uniform.

Organizers frequently host panel discussions, workshops, and events. After waiting in online queues, I was fortunate to get a much-coveted ticket to the museum’s Second Annual Hip Hop Block Party, which in 2023 doubled as a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the musical art form. The event was more than a party. It was a surreal experience to watch performances by some of the hip-hop icons featured in the museum out on the lawn — in the shadow of the Washington Monument.

There’s far more to see here than can be absorbed in a single visit. For me, the core of the experience is a reminder that I stand on the shoulders of the many who went before me. I believe for many visitors, what comes across most clearly is the vital role of African Americans in the growth of this nation. “I have long believed the Smithsonian can be the glue that holds the country together,” said the Smithsonian’s Lonnie G. Bunch III, “even on a topic as challenging and nuanced as race.”

Tykesha Spivey Burton is a freelance journalist and photographer whose work has appeared in British Airways High Life, Travel + Leisure, Fodor’s Travel, The Telegraph, and more.

This article appears in the January/February 2024 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you Tykesha, for this article on a truly remarkable, unique, wonderful museum. It covers the broad spectrum of the African-American experience from the inexcusably horrific to the positive and hopeful. Studied as you are on this subject, I can only imagine the painful shock you must have felt on your initial visit at the starting point.

It’s one thing to have a general awareness of what happened from what we learned in school; how wrong and bad it was, and quite another to see and hear it in the physical, as only a museum can present it. Seeing the iron shackles and the ‘Great Negro Mart’ sign lit up on my desktop, made it that much more shocking than in the magazine recently.

I appreciate how the museum is organized on the various levels, including the Contemplative Court with its soothing, calming waterfall for healing thoughts and reflection. There’s so much to see and take in, one visit isn’t enough. I find this true with museums in general; particularly art, to get the full effect.

The National Museum of African-American History and Culture should be visited by all Americans, AND others visiting D.C. from around the world. Your ancestors are very proud of you. I felt that while writing this, and I am too.