This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As entertainment awards season rolls on, one of the most consistently celebrated performances has been that of actress Ayo Edebiri as Chef Sydney Adamu in the acclaimed TV show The Bear. Edebiri, who grew up in the working-class Boston neighborhood of Dorchester as the only child of a Barbadian mother and a Nigerian father, has been creating, writing, and starring in both comic and dramatic shows for a decade, so this moment is very much about her life and career arcs and accomplishments. But the character for which Edebiri has been honored with numerous awards is also a fictional representation of a longstanding and defining American identity: the Black female chef.

As many scholars have traced, there’s a long and frustrating trend of American women being portrayed in media and framed in collective conversations as cooks, while men in parallel roles are more consistently defined as chefs. As with so many social and political issues, African American women in the culinary world have frequently been at a double disadvantage, stereotyped by both gender and race. Yet despite those prejudices and challenges, we find stories of groundbreaking Black women chefs who have significantly influenced not just food but all of our culture. Here are five of those impressive figures.

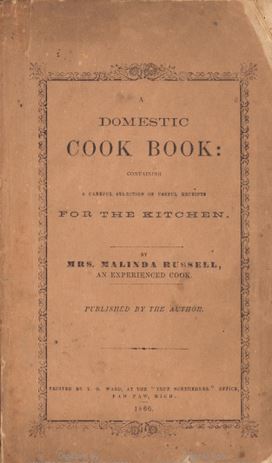

1. Malinda Russell

The histories of Black women chefs are as intertwined with those of slavery and racism as every other aspect of American culture. And no story better illustrates those interconnections than that of the groundbreaking cookbook author Malinda Russell. Born free to a formerly enslaved African American mother in early 19th century Tennessee, Russell was taught to cook by another enslaved Black woman, Fanny Steward, and began to make a living as a traveling chef. Russell eventually was forced to flee the South when her home was attacked by a white supremacist mob during the Civil War, and she and her son relocated to Michigan. There she supported her family by self-publishing A Domestic Cook Book: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen (1866), which begins with an autobiographical sketch and then features numerous recipes and tips that significantly influenced subsequent American chefs.

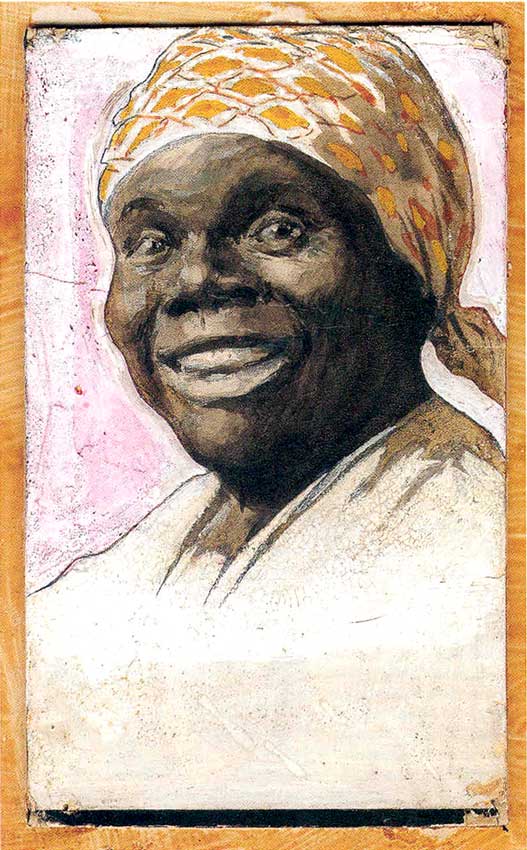

2. Nancy Green

A few decades after Russell published her cookbook, a formerly enslaved woman became the literal and figurative face of a national culinary brand. The R.T. Davis Milling Company was looking to market their pancake flour at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition through a new “Aunt Jemima” character, and hired Nancy Green to perform and cook as Jemima at the fair (and under contract thereafter). Born into slavery in 1834 Kentucky, Green had moved through a series of professional roles in the years after emancipation, but cooking was a consistent part of her identity, and it’s important to note that her performance as Jemima was much more than just modeling or acting: At both the Exposition and her subsequent tours, she cooked pancakes for her audiences. While Jemima was a deeply stereotypical character, she was also an opportunity for Nancy Green to connect her culinary skills to a chance for professional and personal prominence.

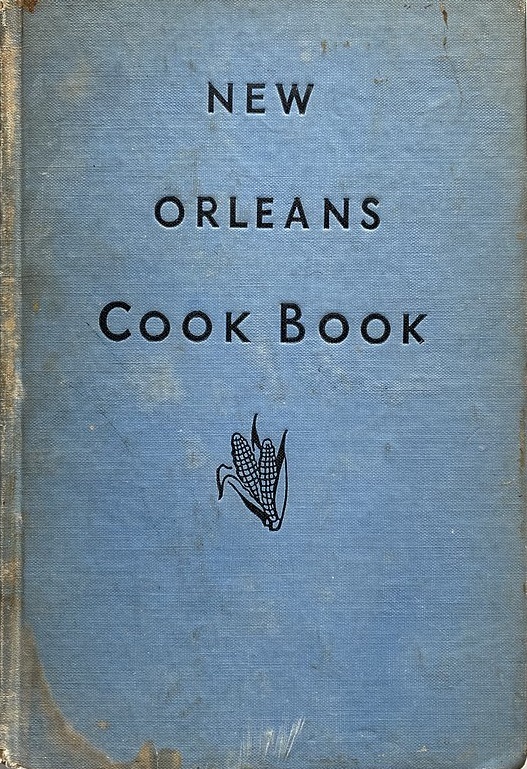

3. Lena Richard

Born outside New Orleans in 1892, Lena Richard was just two years old when Nancy Green cooked at the Columbian Exposition, but over the next few decades she would become another face of American cooking and the culinary industry. That career started with domestic work for a prominent New Orleans family, extended into an education at Boston’s Fannie Farmer Cooking School in the 1910s, and then exploded with a series of successful catering services, restaurants, and other culinary endeavors in 1920s and ’30s New Orleans. Richard’s career culminated with two complementary successes: founding a cooking school with her daughter Marie in 1937, and publishing her New Orleans Cook Book with Houghton-Mifflin in 1940. And in 1949-50 she hosted one of the first televised cooking shows, Lena Richard’s New Orleans Cook Book, broadcast on New Orleans’ first TV station, WDSU.

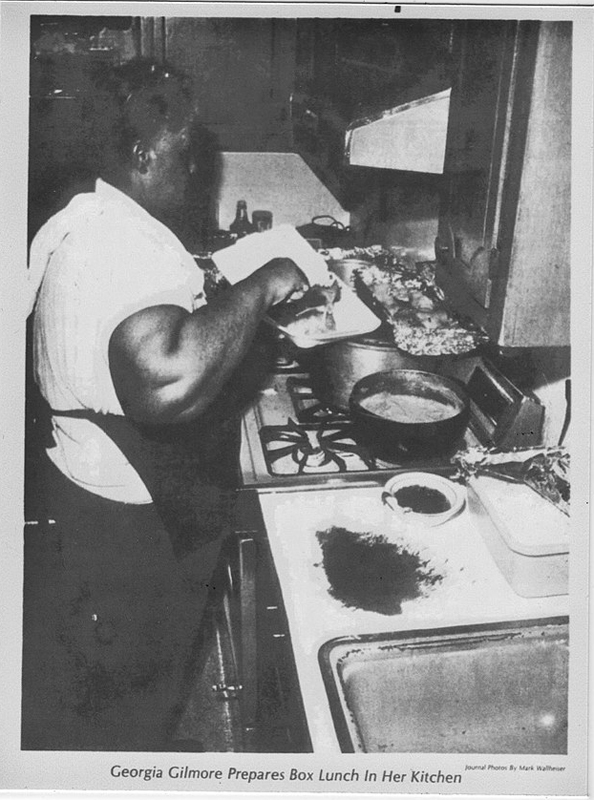

4. Georgia Gilmore

Just a handful of years after Richard’s TV show aired, the civil rights movement began in earnest with the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott. As I highlighted in one of my first Considering History columns, that boycott was driven by Black women activists, and its participants were also fed and funded by a very impressive such woman, Montgomery’s own Georgia Gilmore. Gilmore was both a chef at the city’s National Lunch Company and a member of its NAACP chapter (alongside Rosa Parks and others), and during the boycott she brought those sides of her life together by founding an organization, the Club from Nowhere, which both fundraised and cooked for all those taking part in and supporting the boycott (including visiting luminaries like Martin Luther King Jr.). Moreover, the fundraising efforts were themselves linked to Gilmore’s culinary talents, as she and her friends prepared chicken dinners, cakes and pies, and other items in her home and then sold them throughout the city. Black women were the backbone of the civil rights movement, and in Georgia Gilmore’s case they were also its satisfied stomach.

5. LeDeva Davis

Much of the story of American cooking over the last half-century has unfolded on TV, and no single figure better embodies the rise of food TV in and after the 1970s than the Philadelphia dancer and educator turned celebrity chef LaDeva Davis. Davis had been teaching dance and art in the city’s public schools for 15 years when she was chosen to host the nationally syndicated PBS show What’s Cooking? in 1975, making her the first Black woman to have such a national TV program. Davis was not a professionally trained chef like the other women I’ve featured here, but she and her show brought images of a Black woman cooking into countless American homes, expanding the legacy of all these foundational figures.

Here in the 21st century, there’s no shortage of famous and successful Black women chefs, working in restaurants and media alike to further advance American culinary and cultural trends. Let’s celebrate and enjoy their tasty contributions this Women’s History Month.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Professor Railton, thank you for this insightful feature on these 5 Black female chefs, spanning the 19th to the 21st century. I appreciate the links you included. One led right to Carla Hall of ‘The Chew’ who’s now on her own show ‘Chasing Flavor’. I’m sorry the previous show was cancelled several years ago, but really ONLY because of her.

I’m impressed with all of these women going in chronological order here, but probably Nancy Green the most for her embracing the Aunt Jemima character, parlaying her into professional and personal prominence she likely wouldn’t have had the opportunity to otherwise. She knew it was a stereotypical character (of course), but it was her ticket to ride, and she did.

She was a real cook, and I’m sure a great entertainer at the same time. As long as she was paid and treated fairly, I see nothing wrong with it—for back then. Hopefully she was proud of what she accomplished, as she should be. I’m not sure how she’d feel about the dissolution of the Aunt Jemima name and image she worked hard to build.

The 1989 image refresh took away any connections to the AJ of old except for her happy, smiling, welcoming face. A contemporary, modern woman few if anyone had a problem with, until 2020. The Pearl Milling Company label just isn’t the same. If Ms. Green were around to know this, I think she’d be philosophical about it, but probably a little disappointed and sad as well.